At its core, Criminal Justice is a tale of small miscalculations leading to grave consequences, feels Sreehari Nair.

Sanaya Rath, tipsy, sad, restless and overcome by sadomasochistic desires, pulls out a kitchen knife and initiates Aditya into a stabbing match.

He inflicts the first wound, and watching him fret over it, she cannot help but be drawn to him.

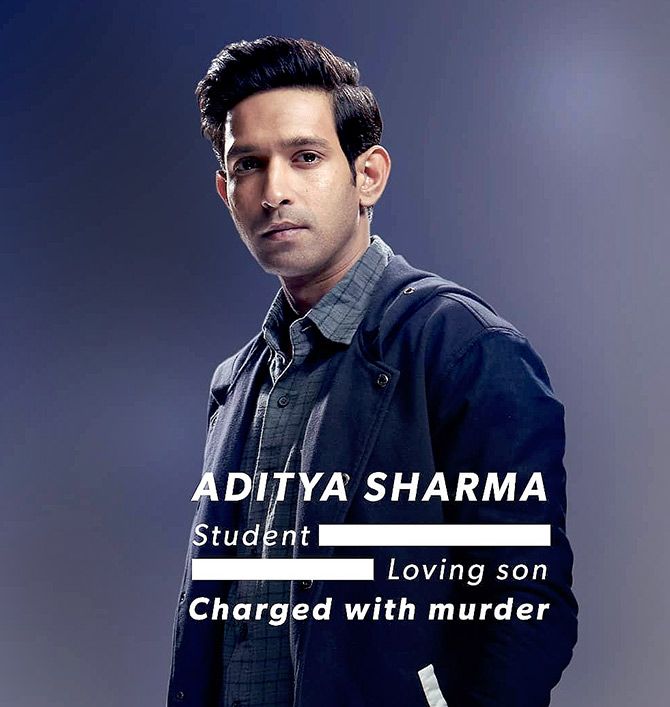

Aditya (played by Vikrant Massey) wakes up a few hours later, with drugs, alcohol and dangerous sex still in his veins, and finds Sanaya dead.

There are stab marks all over her body.

But she hardly looks violated.

In fact, there’s something else written on her face.

It might have been calmness or poise.

It might even have been satisfaction.

This incident, at the centre of the new Hotstar Special, Criminal Justice, is, every bit, the perfect incident to illustrate how *inadequate* the legal process of any country can seem (given this is an official remake of a British show, we can surmise that at least one Brit feels this way too), when dealing with crimes of a peculiar nature.

To the audience, the suggestion is pretty clear: Here’s a game of 'searching for sexual pleasure’ gone horribly wrong.

However, when viewed through the eyes of the law, the possibilities are rather conventional: Murder, because it involves death by stabbing; and rape, because the death was preceded by sex.

Although Aditya cannot exactly remember the details of the fateful night, he would be hard-pressed, even if he did remember the details, to explain why he is not culpable.

It’s these complications that make Criminal Justice more than just a whodunit.

As a matter of fact, the show hinges on the doubt implicit in Aditya: who himself isn’t sure, if he’s guilty or not; or if the terms ‘guilty’ and ‘innocent’ can be applied to his involvement in Sanaya Rath’s death.

Aditya was, for a brief period, a citizen of that thin line that separates Impure Thoughts from a Heinous Act and it’s ironical, almost funny, to see, how casually he crossed into hazardous territory.

Norman Mailer in The Executioner’s Song and Dileesh Pothan in Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum had demonstrated how an oddball, who knows both sides of the law, can expose the gross imperfections in a legal system (however well-intentioned) that takes on the right to deem people 'fit' or 'unfit' to live in society.

Criminal Justice also aims to achieve the same effect and expose the same set of imperfections. But, at its core, it is a tale of small miscalculations leading to grave consequences.

And the reason why this story outline works independent of socio-political contexts is because it’s based on two universal truths:

1. Legal apparatuses are, by nature, irritated by nuance.

2. Those who exercise the law aren’t equipped emotionally to deal with delicate questions relating to the frailties in human nature.

In any legal case, facts have to be established.

Based on those facts, two ladders of logic are built and whoever builds the better ladder, presumably, wins the case.

There is an iciness about this whole process which, when viewed from a distance, would seem the stuff of Absurdist Theatre. And it is this absurdity that Criminal Justice wants to explore.

Consider, as an example, the following sequence:

When the top cop investigating Sanaya’s death tells Aditya, 'I haven’t met a psychopath like you; someone who would put on a condom before raping a girl,' the cop is using the 'facts' he has gathered to build his own ladder of logic. And although the facts do fit the cop’s theory, it doesn’t quite the capture the reality of what happened inside Sanaya’s bedroom.

In its structure, as well as its tone of voice, Criminal Justice is a Procedural Drama given the benefits of scope and running time, which allows the makers the freedom to assemble the drama out of small bits of behavioural comedy.

When a policeman talks about the 2,500-page chargesheet he is preparing, he is a figure of sadness as well as amusement. The policeman’s throwaway quip suggests that the bane of our various bureaucracies may notbe that they are dissimilar; it may be that they are eerily similar.

Mita Vashisht, who plays a prominent lawyer, whispers her predilections into an assistant’s ear and then, to the judge, she enunciates her words with total authority.

These different speech patterns are wonderful touches.

They are part of the show's controlling metaphor; that the fight for justice is not a pursuit of truth. It’s a confidence game!

Caught in the meshes of this Absurdist Theatre, Aditya has to ensure that he doesn’t become a corpse for the human-vultures to feast on.

He has to learn how to be, at once, trusting and suspicious.

In judicial custody, he encounters prisoners who have become depraved animals. And even as Aditya is devising ways to keep out of this set of individuals, far removed from his own background, he gets chased around by the Prison Homosexual.

Now, our hero is faced with the uphill task of saving both his soul and his hide.

Vikrant Massey is a wonderful performer and here, though type-cast as the ‘sufferer,’ he does not drop his cheerfulness.

The optimism on Aditya’s face, in an odd way, is what gives truth to the paranoid fantasy: you care about him because he hopes against hope.

Of the four episodes I watched, the first two, mounted by Tigmanshu Dhulia, were clearly the better-directed, better-paced episodes.

Dhulia’s febrile artistic temperament is suited to tackle the interlocking ironies that constitute Black Comedies and his 'emphases' are never de-humanised. Like for instance, even when he shows us the fatalistic side of Sanaya, he finds a way to offer us some insight into her emotional quandaries.

In line with Criminal Justice’s jittery style, the writing by Sridhar Raghavan, too, peaks and wanes.

Many of the wild shifts in tone (especially when the show alternates between hilarious and macabre) have been engineered with great control.

On the other hand, some of the nightmarish aspects, such as the role of the media, seem to have been written in haste. You know the media can affect and distort everything that’s going on but, here, you never gets a clear sense of *how* that third-wheel turns.

A few lines, and some sequences, were perhaps designed to be ‘winks,’ but they have been wedged into the narrative rather clumsily.

Sanya Rath evokes the famous Casablanca line to describe her chance meeting with Aditya ('Of all the cabs in all the towns...' she drones on), but it only prevents the character from coming into sharp, living focus on her own.

A brilliant prison scene from Ek Hasina Thi has been recreated, down to its set-up and punchline, and it simply feels like an attempt at compensating for the writer’s lack of imagination.

Through all this unevenness, what sustain your interest in Criminal Justice are the performances, which belong to two different styles of acting and yet illuminate each other.

With Vikrant Massey, Rucha Inamdar (as Aditya’s sister) and Anupriya Goenka (who is the lawyer’s assistant) you are not aware of any 'performance’ because they play characters that are peering into the system.

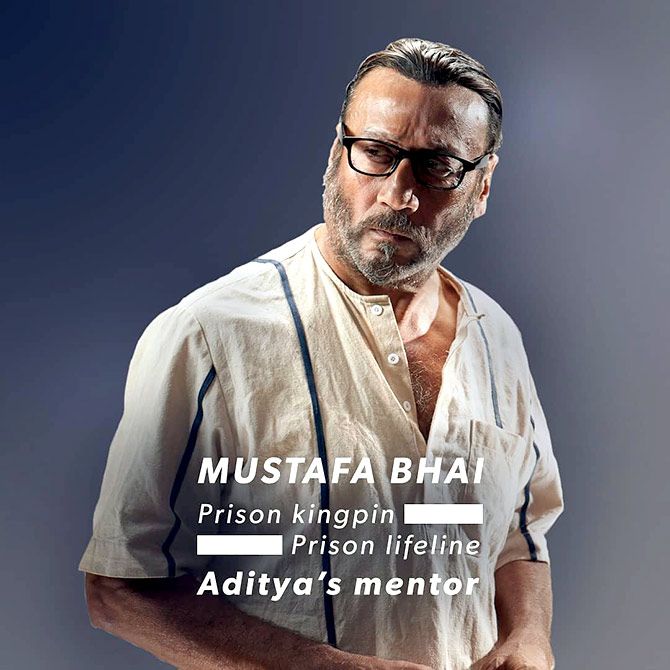

With Mita Vashisht, Pankaj Saraswat (the top cop) and Jackie Shroff (who is shown to be running a parallel government inside the prison), you are ‘aware of the performance’ because they play characters whose modulated *outer appearances* are key to their existence.

It is Pankaj Tripathi, however, as Madhav Mishra, a hustler of a lawyer who flits effortlessly between the two styles of acting, who gets the full star treatment (In the tradition of those great stars, what you first see of the actor are his signature eyebrows).

Communicating to us his uneasiness in the presence of sophisticates, as also his natural, almost middle-class survival instincts, Tripathi has here, very clearly, taken on a half-written character, felt his way into it and filled it with his own humanity.

But then, Madhav Mishra’s humanity isn’t of the straight liberal kindness-variety that so many of our movie critics are accustomed to admiring, and this, almost twisted humanity, is also a part of Criminal Justice’s appeal.

The show seems to understand that totalitarianism does not come from only the right wing, anymore; that the Left, today, is, equally committed to the idea.

Think about it.

How were the nuance-free denunciations of those named in the #MeToo movement any different from the right wing’s nuance-free denunciations of the supposed ‘anti-nationals?’

Wasn’t there an aspect of totalitarianism evident in the manner in which we descended, like scavengers, upon just about anyone who was named; in the way we worked oh-so-meticulously to deny an accused his right to even explain himself; and in how, we rushed, to condemn him to a life devoid of his art and livelihood?

Criminal Justice understands that we live in a world where totalitarianism has become more convenient than nuanced thinking.

The curse of our times isn’t merely that some of us can’t empathise with the Pakistani on the other side of the border.

The real curse is that we are living in times where a person accused of a misdeed, or a person who may have committed a minor transgression, has started seeming as foreign to us, as the man from Mars.

© 2025

© 2025