'Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga is a step backward for the portrayal of female camaraderie in our movies,' argues Sreehari Nair.

Long before I knew anything about sex, let alone same-sex love, I had seen my mother in bed with another woman.

There they would be -- mother and friend -- both wearing maxis with floral designs, engaged in tête-à-tête, the intensity of which would loosen the spring in their joints, prompting them to suddenly go down on the bed together, eyes locked, legs still crossed inside their satin maxis.

And here's the funny thing about that whole ritual, now when I look back on it.

Despite their show of closeness, the conversations never once waned. So discuss they would, their husbands's digestive problems, children's education, and the rising price of fuel -- all the while, feeling a new set of earrings, or praising a freshly purchased anklet.

While this may strictly be a nugget of personal memory, hidden inside it, I believe, is a universal truth: Women (gay or straight), aren't too precious about maintaining physical boundaries when they interact with one of their own gender.

A woman can ogle at another woman or compliment the skin tone of a totally stranger dame she might meet at a bar counter. Two women can adjust each other's clothing, and hug and touch each other on the arm, with none of the inhibitions that two straight men may demonstrate.

It is this rather basic characteristic of women -- born perhaps out of the feminine instinct 'to nurture' -- that gets a bad rap when Director Shelly Chopra Dhar serves up some tame rites of lesbian romance in her film Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga.

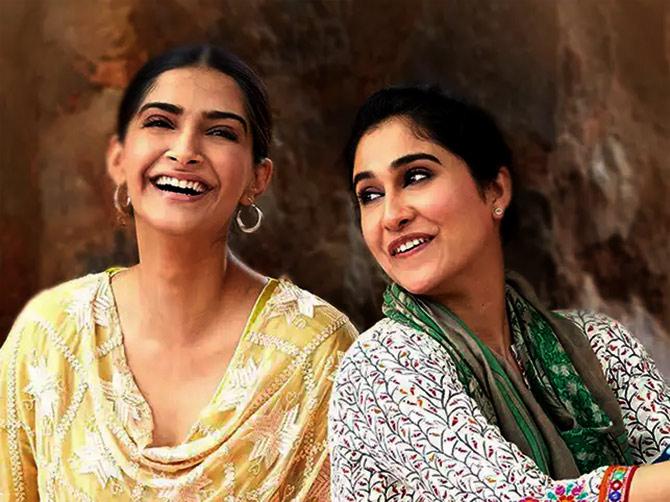

In the logic of the movie, when the two lovers, Sweety and Kuhu, are only allowed a few embraces and some kisses on the forehead, and when they are 'called out' for doing just that much, it isn't queer courtship alone that gets misrepresented.

What dies in the whole sanitisation process is an honest depiction of how women behave in each other's company. For -- and this is the plain fact to consider -- in real life, two straight ladies would have gotten away doing a lot more than what Sweety and Kuhu, in this picture, get chastised for doing.

Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga may, thus, have done nothing for lesbian love, but, more notably, it is a step backward for the portrayal of female camaraderie in our movies.

And while this problem may sound specific to the film, let me tell you, it points to a larger malady that plagues the Hindi film industry; the malady itself a product of Twitter-era bravado: Of wanting to be 'progressive' than wanting to be 'true'; of wanting to 'instruct' than wanting to 'dissect'.

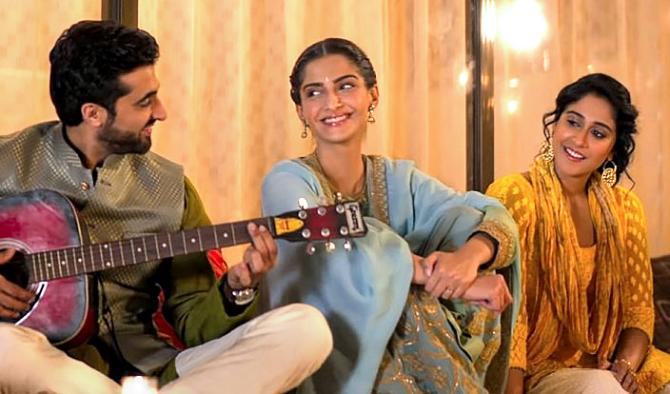

Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga is pitched as 'progressive cinema'. Meaning, almost every element in the film, is chiefly at the service of perpetuating its image> -- with nothing confirming this better than Sonam Kapoor's breathy performance as Sweety.

As an actor, Kapoor is not without her strengths (look beyond the self-seriousness of Neerja to her wonderfully boppy turn in Khoobsurat), but her performance here isn't merely bad; it is the sort of performance that shouldn't have made it to an editing table.

If you were left wondering how, a director of a major motion picture, could have okayed those shots of wheezing, I suppose, you still have some learning to do about the tenets of 'progressive cinema'.

One tenet being that when cinema aspires to be as progressive as Ek Ladki Ko..., an aspect, such as the quality of a performance in it, becomes close to inconsequential.

So Sonam Kapoor's Sweety isn't expected to be a real person; she's only a carrier of a thesis. All that wheezing, though phony in its rendition, is perfect for the thesis's health: Read it, if you will, as the yelp of the repressed lesbian.

And yet, those small everyday truths, which get overlooked when cinema tries to be 'progressive' at all costs, are the truths, which when realised, have the power to break down the invisible fences that exist between the viewer and the screen.

Watching the 'highly cultivated' lesbian dalliances in Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga, I was reminded of a scene from Ingmar Bergman's boudoir farce, Smiles of a Summer Night.

In it were Ulla Jacobsson and Harriet Andersson, playing mistress and servant, who in a moment of sheer girly amity, plop down over a king-sized mattress and roll around in mirth. Smiles of a Summer Night may have turned 63, but even today, every time that scene plays out, it's as though I can touch those actresses.

Bergman, there, wasn't out to be progressive. But, through photographing that small act of intimacy, set inside a turn-of-the-century Swedish mansion, he had magically wrenched into existence, the bonhomie that I had seen heterosexual women in my middle-class, suburban Mumbai home, share.

In that moment of physical closeness topped with giggly laughter, cinema and cinema watching must have moved forward silently, as it must have, when Satyajit Ray got his women to tie each other's pigtails, when Bertolucci's Parisian matrons decked up suicides in shiny bridal wear, when Almodovar's housewives sang as they sliced tomatoes, and when Rima Das's mothers pinched lice out of their daughters's hair.

Cinema and Cinema Moments like these are beyond 'Progressive'. They are what you may term 'Radical' -- for they take us one step closer to our shared yet undocumented small truths.

These are revolutions without placards, and have no slogans to prop them: Only a film-maker's genuine curiosity.

It is Bergman's curiosity for the feminine universe which gives that passing scene of intimacy its timelessness. On the other hand, when Ek Ladki Ko... substitutes an honest dissection of camaraderie between women with speeches about inclusiveness, what it is trying to hide is its lack of curiosity for women.

And an Indian movie-watching audience of 2019, can, I think, intuitively sense this: Here's an audience for whom grand statements matter, only if they emerge out of little details, honestly portrayed.

Baradwaj Rangan -- who is never anything less than perceptive about the mechanics of popular cinema -- says in his review: 'In Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga, there is a great debt to our biggest hetero-romance, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. We get the mustard fields. We get the big wedding celebration, a closing scene set in a railway station.'

As astute as Rangan is in his reading here, the problem with simply inverting the familiar elements of hetero-romance, while falsifying the ‘key experience’ at the centre of the film, is that it renders Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa as nothing more than a parody.

And while a lot of the discussions around the picture seem to suggest that it is an improvement over something like a Dostana, quite frankly, it isn't.

As a matter of fact, it's Dostana all over again, but without the insensitivity of that one -- which insensitivity, had, oddly enough, offered the audience a way into that film. (Critics often fail to examine the value of Bad Taste: About how much of a guide and unifier Bad Taste actually is).

Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga's final act, featuring a play about Sweety and Kuhu's doomed romance, is almost a dare, aimed straight at the viewer.

On the screen, as a few audience members are shown to get up and walk away during the play, and a few others grumble about, and some sit there, entranced, their faces stentorian in their identification with the plight of the star-crossed lovers, the film seems to be goading you to take up one of the three positions.

Mine was number four: Indifference. Not one of the three original positions, but given the groans and sighs of those around me in the theatre, a popular one nevertheless.

I wasn't expecting any boldness from Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa, but I wish it was as committed to the small truths of its world, as it was to its message. I wish it would have prompted some people to actually walk out: Wish it had shown the courage to lose a good many apostates in order to gain a handful of loyal followers.

I get it; this is 'mainstream cinema', which is the other name for cinema that is meant to lull you into a state of security. But how can we expect art to begin uncomfortable conversations without disturbing the comfortable?