Several leading scientists, academicians, and agriculturalists have called for raising government support for research and development to make Indian agriculture future-ready.

A few weeks back, agricultural scientist R S Paroda made an impassioned plea before a top official of the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) to increase the research budget for farming and allied activities in the country to meet the numerous challenges facing the sector.

Paroda, founding chairman of the Trust for Advancement of Agricultural Sciences, said the budget for the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) should be raised to facilitate more focus on research and cutting-edge technologies.

ICAR is an autonomous body responsible for coordinating, guiding, and managing research and education in agriculture.

The largest network of agricultural research and education institutes in the world, it played a significant role in the Green Revolution that allowed India to achieve food-sufficiency.

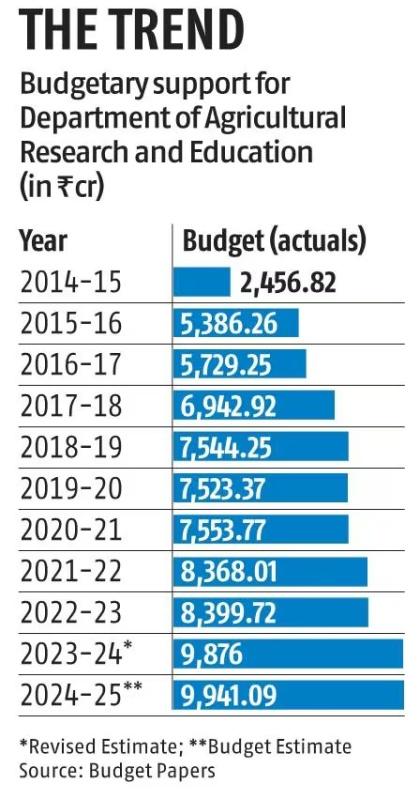

ICAR gets much of its funding from the annual budgetary allocation for the Department of Agriculture Research and Education (DARE).

In response to Paroda's comments, the senior PMO official seemed to suggest that before moving on to fundraising, ICAR needed to consider reforming its functioning so that its manpower and financial resources were better utilised.

He also hinted at several reports that have laid down a roadmap for such reforms and how those could be a starting point.

Paroda is not the first to raise the issue; before him, several other leading scientists, academicians, and agriculturalists have also called for raising government support for research and development to make Indian agriculture future-ready.

In a recent pre-Budget meeting Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had with stakeholders from the farm sector, a majority of the participants, say sources, stressed on the need for enhancing the research budget for agriculture.

A paper last year by the National Institute of Agriculture Economics and Policy Research, which functions under ICAR, found that every rupee invested in agriculture research gave a return of almost Rs 13.85, which is the highest among all activities linked to farming.

The paper also showed that fresh investment in agriculture research had decelerated between 2011 and 2022.

“Looking towards the growing demand for food and other agricultural products and the future challenges to their production amidst little scope for expansion of agricultural land, it is imperative to invest more in agricultural R&D and prioritise it across disciplines or sub-sectors and regions to maximise economic, social, and environmental benefits,” it said.

After research comes agriculture extension activities, which give the second best return on investment (RoI) -- Rs 7.40 -- on every rupee spent.

The paper found significant differences in RoI at the sub-sector level. The ROI from animal science research is significantly higher at Rs 20.81, while for the entire crop science sector it is Rs 11.69.

The study also found significant regional disparities in spending on agriculture research. Between 2011 and 2020, Odisha, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh, which account for 43 per cent of the country's net sown area, spent less than 0.25 per cent of their agriculture GDP (gross domestic product) on research.

On the other hand, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Kerala, and Assam spent more than 0.80 per cent of their agriculture GDP on research and development.

The study also found that the portfolio of agricultural R&D remained heavily biased towards crops.

Livestock and natural resources received significantly less. In southern states, however, the spending is more balanced.

More bang for the buck

Low public funding

In India, agriculture research and development is largely public-funded. The study found that from 2011-2020, Central and state governments contributed 33.8 per cent and 58.5 per cent, respectively, of the total investment in agricultural R&D.

“From 2011 to 2020, India spent 0.61 per cent of its agri GDP on research, which is about two-thirds of the global average of 0.93 per cent,” the study found.

Though India's investment in agriculture research and development, both private and public, has risen almost five-fold during the past four decades, annual growth in research investment has decelerated to 4.4 per cent during 2011-20 from around 6.4 per cent in 1981-90.

This has been primarily due to sluggish growth in public investment and significant deceleration in the growth of private investment, according to the study.

A quarterly bulletin by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations' Centre of Excellence for Agriculture Policy, Sustainability, and Innovations, released last year, underscored the need to double the budgetary allocation for agriculture R&D to broaden its impact.

“Achieving this would require nearly doubling the current budgetary allocations for ARDE (agriculture research and development expenditure) from the current Rs 9,941 crore allocated to DARE within the next two-three years,” it said.

The paper, while advocating relocating funds from subsidies on food and fertiliser towards agriculture research, said that though the National Agricultural Research System under the aegis of the ICAR released 2,380 varieties of various field crops since 2014, El Nino in 2013 brought down agri-GDP growth to 1.4 per cent in FY24 compared to 4.7 per cent in FY23.

“One plausible answer is that whatever has been done so far is not enough to protect Indian agriculture from extreme weather events or there is a serious lack of extension-related activities that might have otherwise aided in research moving from lab to land,” the paper noted.

R G Agarwal, Chairman Emeritus of Dhanuka Agritech Limited, says that in 2024-25 the ministry of agriculture has been allocated Rs 1.32 trillion, which is 2.7 per cent of the total Central government expenditure.

This is a 5 per cent increase compared to the revised 2023-24 estimate of Rs 1.26 trillion. However, it is crucial for the government to prioritise increasing investment in agricultural research to address the sector's growing challenges, Agarwal says.

He adds that this is essential to boost productivity and develop improved seed varieties for crops such as pulses, wheat, oilseeds, and cotton.

The government should allocate more funds and offer tax incentives to encourage private sector innovation, driving sustainability and resilience in Indian agriculture.

Where money goes

Previous Budget documents show that the annual budget of DARE, under which ICAR falls, is about Rs 8,500-10,000 crore in the last few years (see chart).

In FY24, the Budget Estimate for DARE was Rs 9,941.09 crore. However, of this around 64 per cent was earmarked for ICAR's Delhi headquarters.

The Budget document footnote says the allocation for the Delhi headquarters is primarily for salaries, pensions, and expenses on administrative and logistical support for different schemes under ICAR in order to implement them efficiently.

In contrast, Bayer, which is one of the world's largest agri-sciences companies, said in a statement in March 2021 that its annual investment of Euro 2 billion in crop science R&D was nearly twice what its closest competitors spent.

Two things are clear. One, that spending on agri-research needs to be significantly increased to generate any meaningful impact. And two, funds for both DARE and ICAR might need to be directed better.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025