Photographs: Courtesy PR Pundit

To celebrate Independence Day yesterday, two of India's leading designers, Ritu Kumar and Raghavendra Rathore, paid tribute to cool khadi.

Ritu Kumar: The miracle of khadi is that it has survived the whimsical cycles of fashion

The period, pre-1947; the mood, an Indian national identity beginning to find political expression and the struggle for independence gaining momentum. A time when khadi became a symbol of the struggle for freedom and steered the people away from British mill-made fabrics to handloom textiles. It was the first time in the history of any nation that a textile had come to symbolise a movement for independence.

On the one hand were fabrics and styles with a sophisticated sheen, glamorous with satin finishes and heavy embellishments, showing signs of a strong foreign presence. On the other was the raw cotton hand-spun on a charkha, and hand-woven to give a look which was crushed, where no two lengths looked alike. The miracle of khadi is that it has survived the whimsical cycles of fashion.

'The problem is that khadi has come to be associated with what our politicians wear'

Image: One of Sabyasachi's classic khadi ensembles, showcased at the Pearls Delhi Couture FW last monthPhotographs: Courtesy R&PM:Edelman

There is never a season when I don't use khadi as the base of a collection and it always flies off the racks.

Khadi, along with other fabrics indigenous to India, forms a dominant part of our textiles, even as we move into the 21st century. The problem, if one may call it that, is that it has come to be associated with what our politicians wear. Most designers would bear out that it makes wonderful crinkled skirts, kurtis, tunics, churidars and salwars.

Stubbornly, despite the influx of luxury designer brands, this fabric in its multitudinous avatars is part of the fashion scene in India, but is not nearly as ubiquitous as it deserves to be, considering our climate and cultural sensibilities.

'The last vestige of what was once the world's finest cotton spinning and weaving tradition'

Image: A male model poses in khadi pants by Aneeth Arora at the spring-summer LFW instalment this yearPhotographs: Sanjay Sawant

Khadi evokes, for most Indians, the image of a robust, homespun cotton fabric that is porous, cool and absorbent. It could easily be the fabric of choice for our scorching summers or humid monsoons, and it is also surprisingly insulating in the winter chill.

Less apparent to most Indians today is that khadi is the last vestige of what was once the world's finest cotton spinning and weaving tradition. More significant is the support that its production provides to the lives of nearly a million poor artisans, an estimated 80 per cent of whom are women.

'A texture as natural and soothing as skin'

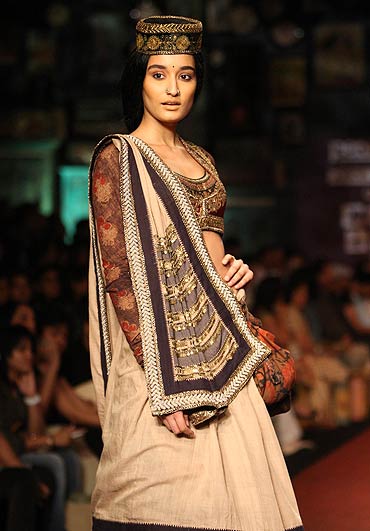

Image: Hand-painted khadi tunic by Sashikant Naidu at the last LFWPhotographs: Sanjay Sawant

Whether acknowledged as a material product, a cultural symbol or an economic aid, khadi derives its distinctiveness from a single textile process, hand-spinning.

It is the processing of turning cotton fibre into yarn by human hands that endows the fabric with its defining material character, its unique tactile quality and unsurpassed comfort level. Repeated washing serves only to enhance these, so that the fabric assumes, over time, a texture as natural and soothing as skin. It was not without reason that India clothed the world in cotton for 2,000 years.

'It gives employment to a million people'

Image: Khadi can be chic too, like this babydoll number from Soumitra Mondal's 2007 'Chowrara' linePhotographs: Uttam Ghosh

The essence of khadi, like any other hand-crafted fabric, lies in its ability to drape as an unstitched garment. It does not have the pliability of, say, jersey or other mill-made fabrics which tend to drape once cut and stitched. This essentially gives a limited scope to the styling of khadi. It is best worn in the same way linen is -- rough and crushed.

The other quality of khadi is its eco-friendliness. At a time when speed, precision and replicability have become the hallmarks of production technology, the wholly hand-spun, hand-woven, and hand-patterned fabric is a product of ultimate luxury. The product gleaned from such a process has a unique distinction and sensibility. The fabric is not produced in an atelier, nor is it rarefied in its production, but gives employment to a million people. It is in our national interest to portray this fabric as a most coveted one.

'Thousand of yards of 'imperfect' khadi rotting in warehouses'

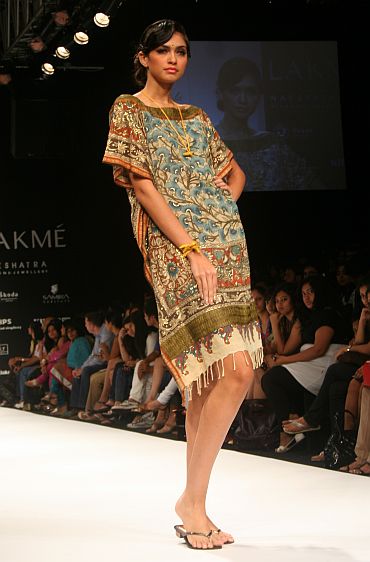

Image: Tupur Chatterjee models a tartan-print khadi outfit by Asmita Marwa at the 2010 LFWPhotographs: Sanjay Sawant

As a fashion designer, one has often wanted to marry the elements of khadi with, say, more uniformity, more pliability and more adaptability. If this could be achieved, it would by far surpass any other fabric in our country.

There have been alternatives like the amber charkha, that only requires one to turn a lever by hand and not draw the yarn from the cotton sliver. This, in essence takes away some of khadi's charm but is not a bad alternative to mill-made fabrics.

Other versions of khadi like poly khadi, where polyester is used with spun yarn to produce a far more 'engineered' fabric, have made an appearence in the market. The government should give technology inputs to the institutions producing the fabric, so that they can produce fabric of a uniform quality, which arrives clean and unstained. Currently there are thousand of yards of 'imperfect' khadi rotting in warehouses, and of no use to anyone.

'Is it asking too much of our government to preserve khadi?'

Image: Designer Ritu Kumar backstage at fashion week a few years agoPhotographs: Jewella C Miranda

As all cultures in the world become more sophisticated, the appeal of khadi acquires a haute couture, albeit non-ramp appeal. It is the ultimate 'poor look' -- for someone who has everything and has acquired all manner of goods, an antidote to conspicuous consumption.

And most essential are the colours on khadi. The slubby cotton dyes beautifully and even bright acid colours take on a language of their own as the fibres tend to diffuse the colour to look rich and earthy.

The fact is that this fabric can be produced in bulk, given the right institutional and design inputs. If uniform quality was made available, then mass shirtmakers of brands like Allen Solly, Van Heusen, Zodiac etc could make khadi shirts, which would give a big boost to the mass consumption of this fabric.

I have often been asked this question: Why is khadi more expensive than a mill-made fabric, and then why is there this perception of it being a 'poor' fabric? By default, we all partake in the responsibility whenever we allow a skill to be lost without contributing to replace it. Is it asking too much of our government to preserve khadi, to not allow the skills of a million textile craftspeople to be wasted?

'Why does khadi as a brand have a 'discount' implication in the country of its birth?'

Image: Khadi dress by Bibi Russell from the Kolkata Fashion Week, September 2009Photographs: Avishek Mitra/India Blooms News Service

Raghavendra Rathore: We need to liberate khadi from the Bhandars

Imagine you are at an airport in a foreign country.

Having checked in, and with time to spare, you start strolling through the labyrinth of boutiques that showcase a whole range of lifestyle and other products.

Suddenly, you stumble across a store called 'Khadi Wadi'. Curiosity stirred, you wander into the store and are surprised. Every product has the lustre of an international designer brand conveying a sense of having been designed in a Parisian atelier, imbued with the reassuring feel of luxury.

And then you notice the tag that says 'Concept Khadi -- 100 percent Indian'. Why, you wonder, hasn't anyone in India done this yet? Or rather, why does khadi as a brand have a 'discount' implication in the country of its birth?

'This product needs a 360-degree approach from concept to the final stage'

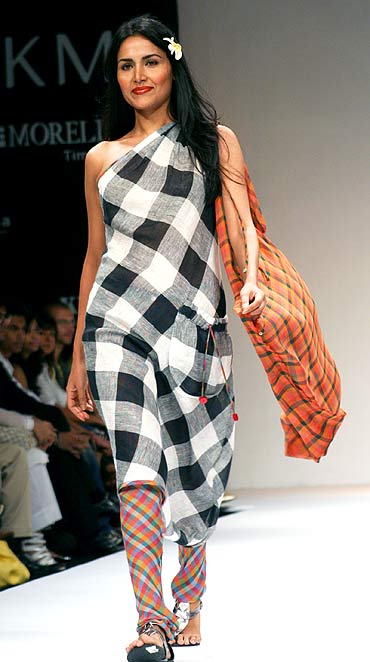

Image: Khadi dress by designer Anuj Sharma, showcased at the LFW last SeptemberPhotographs: Sanjay Sawant

It doesn't take much to realise that there has been virtually no effort to promote the 'concept' of khadi. It is more of a fits-and-starts approach fuelled for brief periods by concerned individuals, charitable agencies, national celebrations, hopelessly lethargic Khadi Udyogs, unimaginative policies and a system that's neither accountable nor responsible.

But this product needs a 360-degree approach from concept to the final stage. The potential of making it a successful luxury product from India is a dynamic possibility. We don't need a think tank to tell us that 'brand khadi', at least in India, has remarkable recall value, something every good marketing professional would know.

'The private sector lacks innovation'

Image: Sahil Shroff in a handspun Aneeth Arora ensemblePhotographs: Sanjay Sawant

The mistake is that we see khadi simply as a fabric, and compare it with other fabrics like linen.

The private sector lacks innovation and cannot find a justification within the cost-versus-profit ratio.

The government does not know how to inter-link it with opportunities that are already present within the system, while designers cannot seem to maintain the consistency and quality that are a basic requirement.

The Khadi Udyogs have been given a mandate by the government to buy what the underprivileged weaver hand-spins.

The weavers, with no exposure and guidance, churn out the same dull patterns and non-luxurious quality of khadi year after year, which finds its way into godowns.

Some of the fabric is converted into 'basic' clothes while the rest is stacked (unimaginatively and for the most part uselessly) in khadi stores -- the Bhandars and Gramodyog Bhavans across India -- a collage of missed opportunities, unnoticed and unresolved.

'We need to make this work'

Image: Designer Raghavendra Rathore on the runway with his models at a showing in DelhiPhotographs: Harshvardhan Sharma

But somewhere in this disorder lies an opportunity. To brand khadi as a technique rather than a fabric.

To get a world-class design house to adapt a hundred-odd designs connecting with all aspects of lifestyle, steeped in the idea of India rather than the ethnicity of the product; then link the whole to the fashion seasons, so the wheel of collections and seasons starts an irreversible turning.

All we need is to apply our minds to make this work.

Comment

article