Prasanna D Zore/Rediff.com

Recovering your stolen phone is an arduous task.

You have to spend money on a lawyer, bunk office to attend court, put up with shabby treatment by the police and dilatory tactics at the courts.

Rediff.com's Prasanna D Zore, whose phone was stolen from a Mumbai local on January 15, 2014, managed to overcome these hurdles and get back his phone 10 weeks later.

Here’s what it took to get it back.

It was not until someone actually stole my phone on a local train that I realised it could happen to me too.

In an operation that lasted barely 10 seconds, my phone was spirited away from the left pocket of my jeans as I boarded the Virar-Andheri train at Malad station.

Gone in 10 seconds!

Realising quickly that my phone wasn’t where it was supposed to be, I frantically asked a fellow passenger to dial my number.

Helpful and empathising but with that ‘oh-here-we-meet-one-more-idiot’ look on his face, he dialled my number.

The phone rang once and then went dead.

I decided to return to the scene of the crime. I got off at the next station (Goregaon) and hurried back to platform No. 2 of Malad railway station.

I had a slim hope that the phone may have slipped under the platform when I boarded the train. But that hope was soon dashed.

I had no choice now but to lodge a police complaint.

The friendly cop at the Malad police station allowed me to make a couple of urgent calls, to a friend in my office and my family, informing them of my predicament.

The police officer then informed me that he could not help me. “All such complaints are lodged with Railway Police at Borivali station. We can’t do anything.”

On a more helpful note, he added, “Please carry your original bill of purchase that has the IMEI number and the stamp of the seller before you go there.”

Armed with a box of documents, I approached the said police station.

And said goodbye to my peace of mind.

Please click NEXT to continue reading...

How I recovered my stolen Samsung Galaxy Note 2

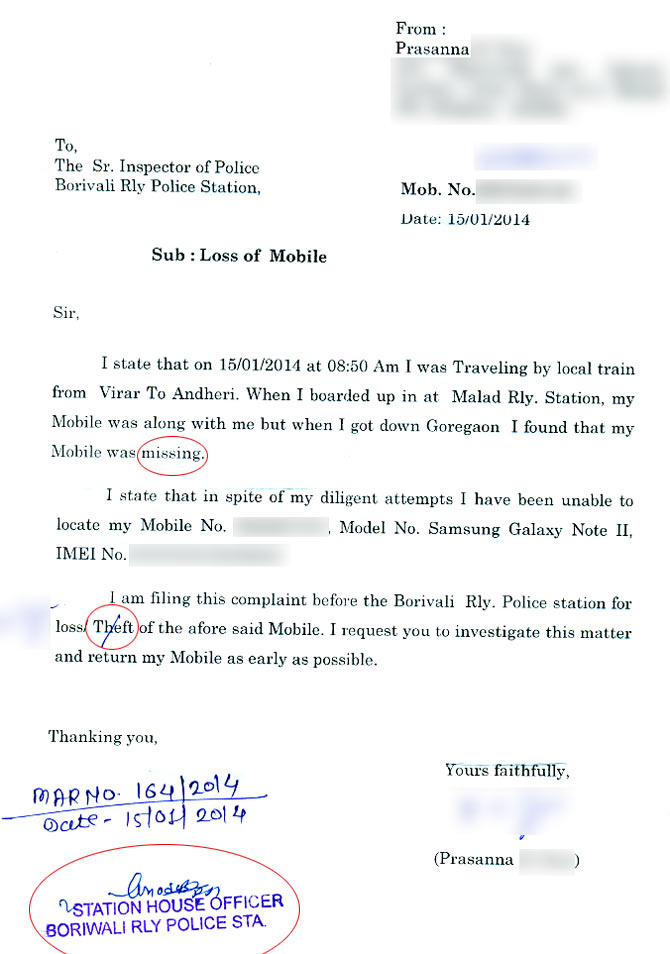

Image: The 'Lost and trace' application.Already there were two people haggling with the cops over lodging a complaint.

It is here I learn that in case of phone thefts you can lodge two types of complaints: Lost and trace; or a first information report (FIR).

Lodging a ‘Lost and trace’ complaint means that your phone was lost (mark the words, please) while travelling and the police will ask your network operator to trace it. Once found, you can get back your property. There is no criminality involved.

A cop I befriended over the next 90 days told me that this technique helps the police suppress the number of crimes taking place in their jurisdiction.

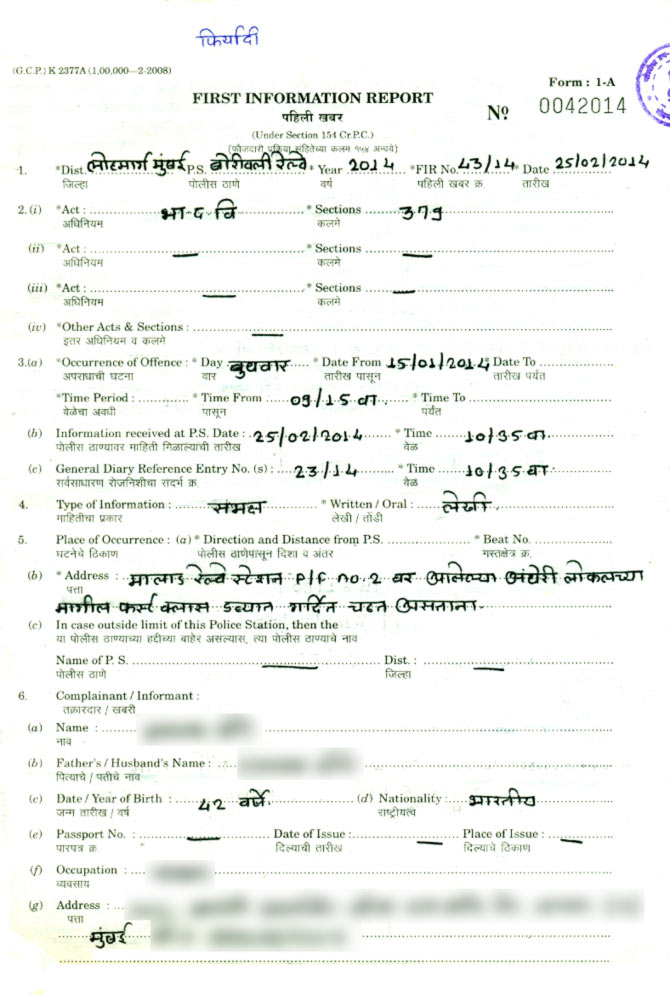

Lodging an FIR puts the record straight.

The FIR registers the incident as a case of theft. A detailed note is made in the register available with the police station. At the end of the process, you get a four-page copy of your FIR, which you have to keep safely till the thief is caught and you go to the court to complete the formalities, that is, if at all your phone is recovered.

If you go for ‘Lost and trace’ you get a piece of paper with the stamp of the Railway Police (in red oval at the bottom of the picture) as acknowledgement. It says that you have lost your phone (as against someone stealing it) and the police will return it once they get it.

To get this case registered, the cop directed me to the typist of his choice to get the ‘Lost and trace’ application typed on a piece of paper. I got a stamped photocopy for my record and the cops kept the original.

The ‘Lost and trace’ application mentioned my name, the phone’s make, its IMEI number (the most important piece of info that helps the cops track and trace your phone once it gets active), my address and an alternative number where I could be contacted if my phone was recovered.

All this cost me Rs 200. Don’t even try to argue with the typist for this extravagance. There is ‘speed money’ written all over her face.

Also, written on her face is the ‘cut’ that the cop will get from the 200 bucks I just parted with.

Before I leave, the friendly cop assures me my phone will be traced in the next 35 days and they will inform me on the number provided.

“We trace almost 60 such phones every month,” the investigating officer boasted.

What if they don’t?

“Please come and enquire with us,” he replies.

Please click NEXT to continue reading...

How I recovered my stolen Samsung Galaxy Note 2

Image: The front page of the FIRI got many calls in the next 35 days, but none from the cops.

I waited another 10 days before approaching the cops.

“You said you recover 60 such phones. What happened to my phone? Were you able to trace it?”

No, says the cop.

It’s been 45 days now and I am getting desperate.

“I want to lodge an FIR,” I insist.

The officer who helped me file the ‘Lost and trace’ application tries to dissuade me. “Why get into the court ka matter?” he reasons.

But I am determined to file the FIR, and spend the next 30 minutes insisting I be allowed to do so.

Finally, the officer, who became a friend later (sometimes, being a journalist helps?), and provided many insights into the machinations of dealing with such cases, came to my rescue.

He directed his junior officer to file the FIR. He gave me his number and told me to call him after a week.

“There’s good news, Zore saheb,” he told me a fortnight later on the phone. “We have caught the thief and recovered your phone.

“Please come to the police station and you will have to do a ‘small court procedure’ before we can return your phone to you.”

This was on March 20, more than two months after the phone was stolen.

“Long live the police!” I shout at all those who blame the cops for being inefficient and corrupt, which included me.

Little did I know the labyrinthine system I had taken on.

The friendly cop asked me to appoint a lawyer who was his friend and thus would charge me "just Rs 2000" when he charges others Rs 3000.

I didn’t know how to react. To get my own phone back, I had to shell out Rs 2000!

But that was not to be the end of my ordeal.

Please click NEXT to continue reading...

How I recovered my stolen Samsung Galaxy Note 2

Image: The copy of the original billThe lawyer makes me sign an affidavit called ‘Return of Property’ based on the FIR I had lodged. To get the affidavit I pay Rs 50 to the typist.

The lawyer tells me that I will get my phone in my hand in no less than two hearings. The first hearing will be when my case is heard before a magistrate who will pass an order to the effect that the phone with the police, with the IMEI number mentioned in the FIR, belongs to me and that it should be returned to me.

For this, the lawyer said, I will have to bring my original bills to all the subsequent hearings. “The magistrate will see the originals,” he said.

I filed the ‘Return of Property’ affidavit in court on March 20. I was summoned for the first hearing on March 29.

All I was asked at that hearing was to state the date on which my phone was stolen.

I was asked to appear before the court next on April 5.

On April 5, the magistrate was on leave. Next date: April 13.

On the day of the hearing I am told that the Railway Police at Borivali station have yet to forward my case file to the court.

“The police want speed money, I think,” I say to my wife who had accompanied me that day.

“Nothing doing,” she scolded.

Next date: April 19.

The magistrate is on leave again.

Next date: April 23.

The police are yet to forward my file to the court. My lawyer, acting holier than thou, abuses the clerks at the police station after seeing the disappointment on my face.

It fails to impress me. “Please tell the cops at Borivali Railway police station that I am giving them power of attorney to attend my case and keep my phone with them. Let them sell my phone and keep the money with them if this is all that they want,” I spew out in frustration.

The lawyer turns red in the face.

“Nothing doing,” says my wife again when I make another attempt suggesting we bribe the cops.

Next date: April 29.

Meanwhile, fed up of all the delay (tareekh pe tareekh, as Sunny Deol says in Damini), on April 25, I call the friendly cop and ask him about the delay in getting my file to the chief clerk at the Borivali court’s office.

“Election duty,” he offers a ready excuse. “All our cops have been busy with election bandobast (security). “They will be back by April 27.”

“My next date is April 29,” I mutter in frustration.

“Don’t worry, Zore saheb, your file will be there,” he assures me.

“Do you think we should give something to these cops lest they once again fail to forward my file to the court?” I dared ask my wife again.

“Nothing doing,” she responds patiently.

On April 29, my case file is on the clerk’s desk. He calls out my name and my case number.

I am asked to stand in the witness box. The clerk asks me for the original. The magistrate wants to peruse it.

I hand it over to the clerk, who hands it to the magistrate who peruses it carefully.

“Application approved,” says the magistrate.

Hurrah! The phone is mine! I exult.

Nothing is that simple.

The magistrate gives his order at around 3 pm. The court closes for the day at 6 pm.

At 6 pm the chief clerk hands over my case file to a court official who will type the ‘release order’ based on which the cops will hand over my phone to me.

The court official is a no nonsense man who makes his intention clear.

“Mala bharpur kaama aahet (I have lot of pending work to do),” he dismisses me curtly.

The lawyer takes me aside and says, “Please give him Rs 500.”

“But I have already paid Rs 2,000 to you and spent another Rs 1,000 in travelling and for other document formalities. Why shall I give him money when even the magistrate has approved my application?” I ask in disgust.

My lawyer is not pleased and tells me to stand inside the court official’s cabin.

The official knows I am standing there but pretends he hasn’t seen me. He is busy with files that need his ‘urgent attention’ because he has been paid for it.

That is when I fully understand the meaning of ‘speed money’. The others had parted with ‘speed money’.

“Shall we?” I plead with my wife.

“Nothing doing,” she says sternly.

We have been standing in front of the official for 20 minutes when he says, “Get this paper photocopied for me,” handing over a small bunch.

We hurry up to the first floor of the court, spend Rs 20 on the job, and give the papers back to him in ten minutes.

By the time he completes the formality -- affixes the court's seal and types an undertaking which I have to sign and hand over to the police -- it is 7.30 pm. The magistrate had approved my application at 3 pm.

Back at the Borivali Railway police station (a five minute walk from the court), the cop informs us that we will have to wait for 90 minutes because he has to type out a letter that says my phone has been handed over to me, after I sign an undertaking that states that I will have to return the phone to the police in good condition, if asked for, failing which I will have to pay Rs 55,000!

Ninety more minutes? Sure!

What was 90 minutes when we had waited for 90 days, and endured all that pillar-to-post running around?

At around 9.15 pm the senior police inspector at the police station handed the phone back to me.

Enclosed in a transparent plastic bag.

My phone was back in my hands. Finally!

Together with the phone I also received much wisdom.

About what it’s like to be an ordinary citizen (well, my profession as a journalist may have helped) caught up in a system that has contempt for ordinary folk and an insatiable appetite for taking advantage of someone else’s misfortune.

Comment

article