Abhishek Mande

Meet Garima Goyal, who had to give up her dreams because of an irreversible and degenerating eye condition, went on to become one of India's first visually challenged media graduates.

The day before her first history test in the tenth grade, Garima Goyal's mother walked into her room and said: "You have the same problem as bhaiyya."

For a regular 15-year-old, this might have sounded like bickering about the mess in the room, her grades or some such mundane problem.

Garima's brother, Ashish, however was no regular teenager. After that morning, she wouldn't remain one either.

It had been a few years since her brother was diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa, an irreversible and degenerating eye condition.

Ashish Goyal was going blind. And now, so was Garima.

Meet Ashish Goyal, world's first blind trader

A little over 10 years since the day, the two siblings have lost most of their vision.

Ashish has gone on to become the first blind person to graduate from Wharton and is the first blind trader at J P Morgan's London operations.

Garima is one of the first visually challenged media graduates from the Maharashtra State Board of Technical Education. She's completed her course in social communications media from Sophia College -- a major portion of this course involves a strong visual element.

She has around 20 per cent of her sight remaining. This means even when I am sitting at arm's length and waving my hands at her, she doesn't know a thing. All she can see is a vague outline of my head and senses some movement of people behind me.

Garima doesn't wear dark glasses. Instead, she sports a pair of spectacles with a very thick lens that helps with whatever little is left of her vision.

Most of what Garima can see is largely dependent on lighting. Mostly though, the 25-year-old has to make do with a cane.

It isn't a regular red-and-white cane -- it's black and metallic, stylish, with a wheel at the bottom and much longer than the regular walking sticks most of us are used to seeing.

She uses the wheel to draw semi-circles as she walks to gauge the ground ahead.

Often, the stick itself has raised curiosity amongst strangers around her. They want to know what it is and when she tells them, they want to know if she is blind.

"You don't look blind," is something Garima hears very often.

To be honest, at first, she didn't seem like a visually challenged person to me either. Part of it, perhaps, has to do with the fact that Garima is so comfortable with her impediment, she's learnt to overcome it superbly.

A larger part, I suspect, has to do with a different kind of blindness -- ours. We're simply conditioned to believe that all blind people must carry a red-and-white cane and wear a pair of thick, ugly dark glasses.

Garima, though doesn't care or at least won't give the impression she does.

With a sense of deja vu, the Goyals braced to accept a second tragedy

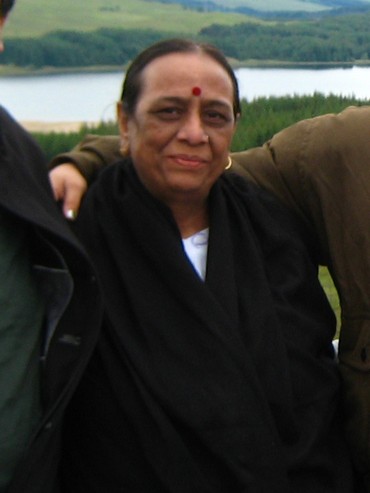

Image: Jyoti Goyal, the mother who stood as a rock behind her childrenThe first thought that crossed Garima Goyal's mind the morning she was told she was losing her vision, was, 'I won't be able to paint anymore!'

Garima was hoping to become a portrait painter. "It was all I wanted to do," she says, more matter-of-factly than with regret.

She'd started drawing when she was four and had taken to watercolours when kids her age were struggling with crayons. All through her school life, she'd painted away. But, just before she was to make the crucial career choice, came the news.

Ashish's condition was discovered a number of years ago. Visits to the family ophthalmologist were frequent during their childhood, since both the kids had glasses from a very young age.

After one such visit, the doctor asked them to wait outside as he spoke with their parents.

On their way back home, they insisted on knowing what the doctor had to say.

Their mother avoided the topic for a few days, then finally broke the news to Garima and her other siblings.

It seemed surreal, and with a sense of deja vu, the Goyals braced to accept a second tragedy in the family.

Garima doesn't speak much about this phase. She says her dad too never spoke about it.

In fact, memories of that day seem to haunt her -- even though she shared what happened, she didn't want any mention of it in the article.

Dad Ashok Goyal, who is in his late fifties, is a property developer and has been responsible for constructing Goyal Shopping Centre -- one of the foremost shopping centres in Mumbai's suburbs.

Their mother, Jyoti, was a college lecturer who quit her job to take charge of the household.

Ashish gave up his dreams of becoming a tennis player

Image: Ashish Goyal his sisters Garima (L) and NehaGarima's brother Ashish's journey -- one of true grit and determination -- also started on a shaky note.

One evening as a child, while cycling, he hurt himself badly when he missed a large pothole. Although he didn't know it then, this was the beginning of his condition.

Later, he began to miss shots while playing tennis. On one occasion, he simply didn't see the ball coming till it hit him on his chest.

That was when Ashish gave up his dreams of becoming a tennis player.

Instead, he excelled in his studies, worked extra hard in his college in Mumbai, then at ING Vsysa, went to Wharton, landed at J P Morgan's chief investment office in London and stuck a thumb at the recruiters who had turned down his application during campus interviews.

Garima clearly had a large pair of shoes to fill.

As the youngest of three siblings -- between Ashish and her, there's Neha who is currently pursuing her post graduation in dermatology -- comparisons with the other two were almost constant.

And while she loved her siblings, she hoped people saw her for who she was and not just as Neha and Ashish's sister.

It was a senior in college who sensed this and offered to help.

"He challenged me to beat his scores. I said it was impossible, but since it is in me never to let my dear ones down, I did my best and graduated with flying colours."

Garima counts her years in college as being some of the toughest.

Coping with her condition during her teenage years was not easy. She remembers jumping into extracurricular activities just to keep depression away.

"Ashish had suggested this. So I started participating in every committee in college," she says. "It was a whole new world and I wanted to experience everything."

At the time, Garima's condition was in its nascent stages. She could still go about her daily routine without anyone noticing the difference.

But, since it would only be a matter of years, she decided to let her friends know.

One of the first people she told was a classmate who told her, 'Main teri secret kisi ko nahin bataaongi (I won't let anyone know of your secret).'

Garima felt somewhat cheated. It wasn't supposed to be a secret. Sooner rather than later, everyone would know.

When I asked her about the most difficult times in her life, she counted this as the first.

"Overcoming depression during my early college years was tough," she said. "That is the age when you want to be a normal teenager, but you get labelled dumb because you cannot complete papers. You try to fit in but you can't."

'I didn't know how I'd do it, except that I wanted to'

Image: Garima Goyal with sister NehaIt took her three years to come out of that phase.

"I used to sit for hours doing nothing. Time and the fact that no one let me give up healed it, I suppose," she says.

The second phase was when she was pursuing her Master's course in Commerce from Sydneham College, Mumbai.

"I was figuring out what to do and was largely at home, learning music and taking some time off. That was when people began to take my presence for granted. Everyone assumed I was only waiting to get married."

Around this time, Garima found solace in writing -- she has two unfinished novels and a whole lot of poems -- and asked herself what she hoped to do in the future.

"Media seemed to be the place where creativity and writing came together," she says.

Garima joined Hindustan Times in Mumbai as an intern to get first-hand experience.

She remembers her first day -- a friend came over early in the morning and helped her go through six newspapers.

For the next three months, Garima worked at their office, where she edited stories for the Metro desk with the help of special software they had let her load.

This was the first brush she had with the outside world. It gave her the confidence to step out of her comfort zone; it also gave her much-needed direction.

Three months later, Garima knew what she wanted to do. She applied for the social communications media course at Sophia College, Mumbai.

"The department had inhibitions as to how a visually challenged would pursue a high-pressure visual course. They communicated their reservations to me.

"As part of the course, we were supposed to make a film, design ads, go out and speak with people. It wasn't going to be easy and I had no idea how I'd do it, except that I wanted to."

Garima started off on what she describes as the third most difficult phase in her life.

'I used to sit for hours doing nothing'

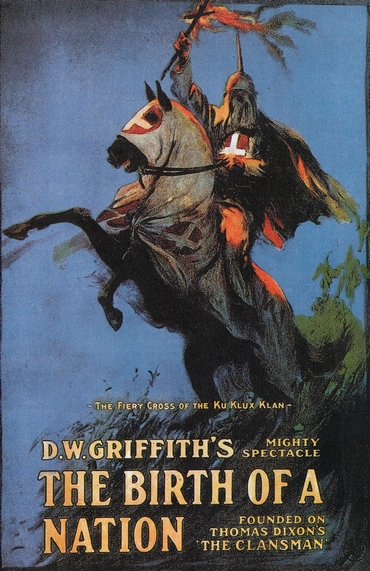

Image: Poster of Birth of a NationGarima's first assignment involved watching D W Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation.

By now, Garima had lost most of her eyesight. But she hadn't stopped going to the movies with her family and friends; she could still follow most of what was going on because of the dialogues and the music.

The Birth Of A Nation however was a different ball game altogether.

Released in 1915, the seminal movie belongs to the silent era.

"There were no dialogues!" she recollects, now laughing. "And it was a three hour movie!"

As she sat through the movie, Garima felt like a fool. "I wondered why I was even bothering to waste my time on this. I couldn't see a thing. I couldn't understand what was going on."

By the time she went back home though, Garima had made up her mind to get around the situation. She searched online for information about the movie, read up on it, researched the hell out of the topic and came back to the next class.

In her semester exam, she would top the film paper.

The year-long course threw more unusual challenges at her. Like the time she stepped out for a vox pop.

"One of my classmates escorted me to the corner of a road and went about her assignment. We'd decided to meet up once we were done. I started calling out to people crossing the road and talking to them.

At one point, I suddenly realised I was talking to no one! The person I had been speaking with had left. More than humiliating, it was scary. There I was standing God knows where and I was all alone."

Garima says the course made her push her limits. It was challenging and affected her health but, she says, it was worth the effort.

Along the way, Garima made friends -- friends who stuck by her, didn't mind being woken up in the middle of the night to talk to her or stop by just so they could do little things for her.

***

Looking back at her achievements, Garima is content. She is currently working with her guru, Balaji Tambe, who runs a holistic healing centre in Karla near Pune and is translating his works into English.

She has never learnt Braille and says technology has helped her get by without much difficulty.

Her phone and laptop have screen reading software that help her read and write.

When I ask her if she's ever felt alienated because of her condition, she tries to think back. "Maybe when I was 16 or 17." After a little while she adds, "I do not recall. The more you collect things, the more difficult it is to move on."

Life may not have dealt Garima a fair chance, but it isn't something she is complaining about; she prefers to focus on her future.

"I am still figuring it out," she says.

The one lesson she's learnt though is to be true to herself at all times.

"Initially, people are sceptical of you. Then, when they see you work, they are proud. Later comes the phase when they begin to expect the best from you. When people tell me how I've changed, I only smile. All along, I have been the same person they were unsure of."

Comment

article