Musicians from across the world will gather in Goa for the Ketevan World Sacred Music Festival.

Their aim? To teach people the value of co-existence, says Ranjita Ganesan.

Can music improve our present historical moment, characterised as it is by intense divisiveness and displacement?

Beauty, goodness and truth are observed across various world cultures, say the organisers of the Ketevan World Sacred Music Festival, and the different musical traditions bring forth these virtues in powerful ways.

First conceived of in 2016, the annual event will try to remind people of the value of ‘coexistence’ by inviting practitioners of sacred and classical music of various eras from countries of the East and the West.

Given the theme, there will be collaborative performances as well as standalone concerts.

It was this opportunity to collaborate that convinced Portuguese vocalist Maria Meireles, who was only visiting Goa in November, to stay back and help manage artistes at the event.

She had met and performed with Santiago Lusardi Girelli, the Argentinian composer who founded the festival and who teaches music at GoaUniversity. Three months on, Meireles is busy checking on visa and flight arrangements for other performers, and preparing for her own recital as a soprano.

The festival name draws from Ketevan the Martyr, the queen of a Georgian kingdom who is believed to have been captured and killed in Iran from where her body was carried to and buried in Goa in 1600.

The venue, the graceful ruins of the Church of St Augustine in Old Goa, is where her remains were discovered some years ago.

Her experiences, which spanned Europe and Asia, also reflect in the festival’s multicultural identity.

Describing itself as ‘an eclectic and vibrating experience of music,’ the festival will offer visitors a chance to listen to the languages and instruments indigenous to different countries, including the UK, Argentina, India, Italy and Spain.

In the line-up is Bach’s Dreams And XXth Century Sounds, which combines ancient sacred chants from different periods and cultures, directed by UK-based Indian conductor Manvinder Rattan.

Soprano Natalia Lemercier of Milan will perform as a soloist in two of the main concerts in the festival.

Some of the international performers have had long-standing ties with India.

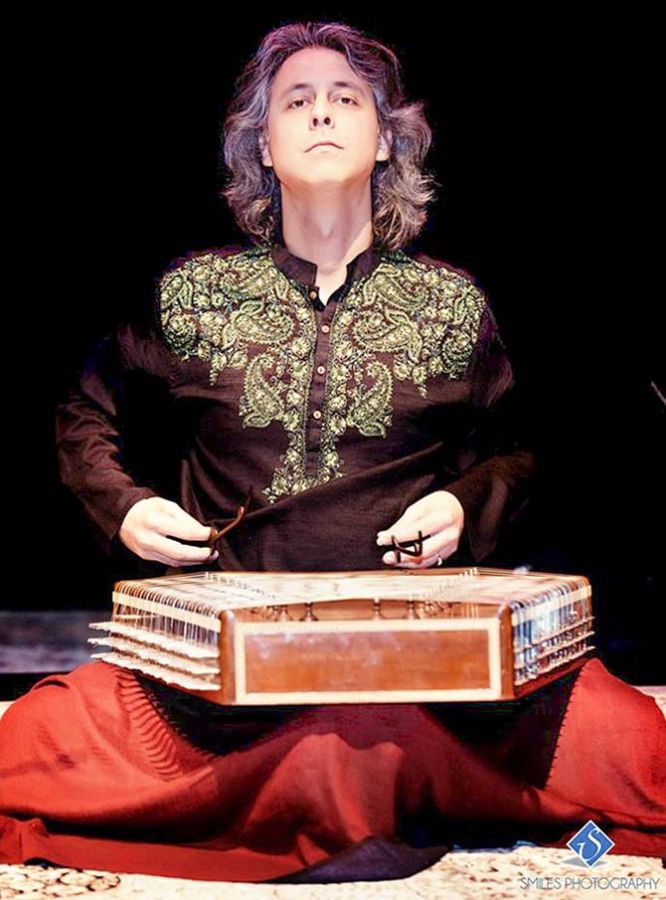

Canadian Jonathan Voyer visited the country 20 years ago as a researcher and discovered and grew to love Hindustani classical music, training in vocals with Somanath Mardur and learning the santoor from Satish Vyas.

He decided to participate in Ketevan to reiterate the function of music in society and “its ability to forge bridges between cultures and its role in making us better human beings”.

Hindustani classical, while not defined as “sacred”, can provoke a profound aesthetic experience that can be qualified as spiritual or sacred, he says.

For practitioners of Western classical music in India, opportunities for collaboration don’t come by frequently, says Swedish founder Jonas Olsson.

So the 16-member choral ensemble he founded, The Bangalore Men, is looking forward to teaming up with the GoaUniversity choir to perform the misatango, a confluence of tango and classical styles designed by Argentinian composer Martin Palmeri.

In a standalone show, the group will play pieces by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg and French composer Francis Poulenc.

“Between the two performances, the music ranges almost 200 years,” says Olsson.

In order to not remain esoteric and limited to the stage, the festival organisers are also planning smaller shows and interactions in schools, churches and old-age homes in the city.

The Ketevan World Sacred Music Festival will be held from February 21 to 24 in Old Goa.

© 2025

© 2025