The Right to Read programme hopes to cover 100,000 schools and 15 million students.

Anjuli Bhargava reports.

The year was 2009.

Venkat Srinivasan, a Boston-based computer scientist, serial entrepreneur and an innovator in the area of cognitive sciences and artificial intelligence noticed a big gap.

He had excellent Indian engineers in his start-ups but almost all of them were not very conversant with English.

This prevented them from interacting directly with their clients across the United States.

Srinivasan tried sending his engineers to popular brick and mortar English speaking schools, courses of various kinds but found nothing really worked.

That's when Srinivasan developed a new technology for the purpose of learning the English language: The Writing Assistant.

In 2011, fate brought Srinivasan and his technology in contact with former India chairman of American Express Sanjay Gupta.

The duo soon realised that the technology developed by Srinivasan could be applied to India to achieve results never seen before and on a scale not imagined before.

Over the years -- in a career that involved travel all over the globe -- Gupta himself noticed two things: India was light years behind other countries in education, literacy and numeracy.

Two, an earlier stint with Motorola had exposed him to what technology and its transformative powers could achieve albeit in a relatively short time frame.

Gupta also felt he must direct his efforts towards the public system for a host of reasons.

The government school ecosystem is where India has the largest scale, it is where the poorest of India's children study and unlike the private budget school space, with the public system, there is regulation and framework.

"It may not be executed well but it exists," explains Gupta.

Moreover, he felt that nowhere on the planet has any country made progress in literacy and numeracy goals without the public system heavily vested in it.

Shortly afterwards, Gupta with a couple of others including Srinivasan registered a company in the US called the English Helper and started to look for ways to make inroads into India's vast public school system.

Until English Helper began, Gupta had been a strictly "corporate" type.

He'd never worked with the government system and 28 states of India sounded a bit daunting but a partnership with the American India Foundation gave him a foothold into around 100 schools they were already working with.

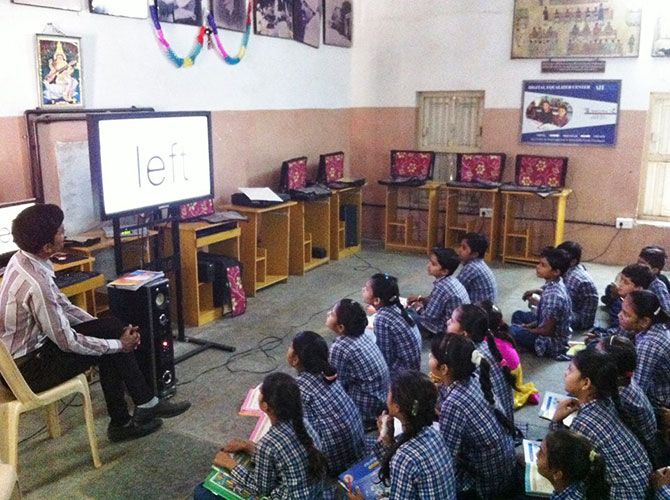

The programme is designed to bring in minimum change so the school's existing textbooks are integrated with software and the teacher uses a projector and a computer to teach.

There is a multi sensory and interactive experience without any new investment in hardware or new IT infrastructure.

The impact in these 100 schools was measured and they found that teacher and student engagement went up substantially.

That's when Gupta felt they could scale up and approached USAID.

In 2015, the Right to Read programme was launched with USAID in 4,889 schools in eight states covering a total of one million children across Grade 1 to 10.

In 2016-2017 third party independent assessments in four of these states -- West Bengal, Maharashtra, Punjab and Gujarat -- showed a 20% improvement in reading abilities across the schools.

Once the model was proven to have a reasonable degree of success, it expanded at a rapid pace.

By 2018, the footprint reached almost 15000 schools and nearly 3.5 million students.

This June, following a highly successful pilot programme in 4,000 schools in the state, the government of Maharashtra has approved the implementation of RightToRead in 65,000 schools in the state for two years.

On an all India level, the RightToRead Program is presently operational in 300 districts across 28 states and 4 Union Territories of India.

Recently, the programme has started getting paid mandates and will be expanding to 2,485 schools in designated minority districts of Assam, Sikkim, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka.

The success of the program has also enabled English Helper to expand to schools in Africa (Sierra Leone and Nigeria), Asia (Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Vietnam) and Central America (Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala).

By the end of this academic year, the programme hopes to cover 100,000 schools in India and the regions it is currently operating in and covering 15 million students.

While this programme targets students who are still in school, what happens to those who are already out of school?

For them a new app called English Bolo has been developed.

The unique feature of this app is distance teaching.

After every eight self-lessons, the student can book a one-hour lesson with a teacher sitting anywhere.

So, a student in Orissa or Jharkhand can find himself face to face with a teacher in Delhi or Mumbai and clear all his doubts in real time.

The first round of funding for English Helper was raised through Omidyar Networks but a large number of Indian expatriates have donated and contributed towards the effort.

A total of $8 million has been raised so far.

Meanwhile back in Boston, Srinivasan -- the serial innovator -- is working on a host of new technologies including Literary Assistant and Gyan.

Many of these he hopes will change the way the world and India learns.

© 2025

© 2025