Meet Bengaluru’s fondest freedom fighter, HS Doreswamy, who has been a sprightly witness to the country's ups and downs since 1947.

It was a cloudy afternoon when I met HS Doreswamy at his modest house in Jayanagar.

His red oxide floored yellow home has bare minimum furnishings, with awards and Gandhi figurines adorning most of the walls and showcases.

The senior freedom fighter warmly welcomes me and excuses himself to go finish his lunch.

Seated comfortably on an old wooden chair, I now watched Doreswamy help himself, with his shivery hands, to small portions of rice and sambar.

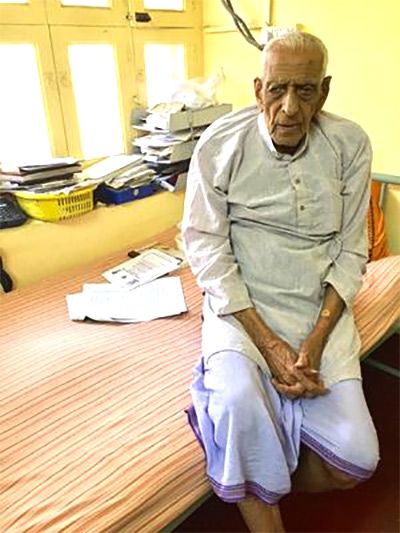

Post-lunch he invites me to sit in his front room where a timeworn bed allows him to rest and talk to people.

A phone call disturbs our conversation before it had barely started.

While he answers the call and replies in commendable English, I take a good look at his heavily wrinkled face for the first time.

It was hard to miss that friendly yet feisty sparkle in his eyes.

Originally hailing from Harohalli, near Mysuru, Doreswamy was mostly educated and brought up by his grandparents after he lost his father at the tender age of five.

Young Doreswamy was witness to a number of Congressmen who frequented his village house to pay his 'Shanbag thatha' (his grandfather who worked as a village clerk) a visit.

"Their (Congress leaders) speeches hugely inspired my family in the early freedom struggle days."

"A very heated and angry atmosphere prevailed across the nation then," Doreswamy recollects.

In high school, Doreswamy read My Early Life, a book that recorded Gandhi's days growing up.

"In one part it said - 'A social worker should embrace voluntary poverty'. This thought particularly influenced me. Though I didn't realise its implications back then, the same philosophy helped me mould my values much later in life," he explains.

Jumping into the revolutionary freedom struggle was an obvious choice for Doreswamy after he moved to Bengaluru for college.

He and his comrades, who also comprised of his elder brother HS Seetharam, were notorious for throwing time bombs into post boxes of senior British officers.

"Our main aim was to destroy important official documents that disrupted British governance in India," he says.

"I was also involved in pacifying mills workers and leaders to shut down mills across Bengaluru that manufactured parachute cloth, a particular clothing material that was used for lining the insides of aeroplanes.

"We wanted to interrupt any kind of industrial activity that aided the British in their World War effort.

"Hence, we convinced ND Shankar, then a staunch Communist leader and mill owner, to temporarily resign from his party, jump into the freedom movement and agitate his staff to cease production.

"We succeeded in this mass awakening and, as a result, Binny Mills, Raja Mills and Minerva Mills shut down for about two weeks protesting against the British. It even inspired many other mills under the then Mysore Presidency to stop working indefinitely," Doreswamy further reminisces.

'Jail was like university for me'

The 99-year-old was also jailed in 1944 after a fellow comrade in custody named him a partner in their bomb-throwing escapades.

"To be very frank, I enjoyed my 14-month stay at the Bengaluru Central Jail.

"It was a matter of pride for about 500 freedom fighters who were locked up there.

"Prison turned out to be like a university for I spent most of my free time acting in dramas, learning new languages and playing volleyball.

"I even took up the responsibility of food administration where I gathered fellow prisoners to join me in shopping groceries from the jail store and cleaning/sorting them," he adds.

After his release from jail, Doreswamy ran a publishing depot Sahitya Mandira for a few years.

However, he had to soon shut it down and move to Mysore to fulfill the last wish of his friend who requested him to carry forward his sinking newspaper, Pauravani to contribute to the freedom struggle.

"I first converted that weekly Congress newspaper into a daily. It was priced at three paisa then.

"During the 1947 Mysore Chalo Movement that forced the Wodeyar Maharajas to accede to India, I got TT Sharma to write 10 strongly-worded opinion pieces for the paper lamenting about the Maharajas and advocating responsible government.

"By the time the eighth column was published, I received a notice from the Chief Secretary asking me to review all articles before a government panel prior to publishing.

"I defied their warning and proceeded with publishing the last two with an exclusive box item where I publicly denounced such an attempt to curb free speech," the firebrand freedom fighter shares proudly.

Doreswamy can recall with vivacity the midnight of August 15, 1947 that ushered freedom to every Indian. The celebration did not seize all night long.

"The festive mood was infectious with people decorating their households with lights and tricolour flags," he adds.

India of his dreams

His excitement dims as soon as I ask him whether he is living in the India of his dreams today.

For someone who believed in Sarvodaya Samaj (progress for all), the India of corrupt politicians and selfish, sham social workers disappoints.

"We fought for an independent India to eradicate poverty, to decentralise power and establish a Janata Sarkar (people's government), but today the governments that rule have no true values.

"They help the rich get richer by encouraging corporate culture. Elections are driven by money power and caste.

"Every candidate is either a BJP, Congress or Communist. What about a people's leader," he asks dejectedly.

I ask if he thinks the present generation values the much priced freedom they fought for.

"Well today only 10 per cent of India is truly free; the rest 90 per cent is not," he quips.

The idea of joining politics never fascinated Doreswamy even through his elder brother was the mayor of Bengaluru earlier.

"The Emergency days and Indira's Congress disillusioned my political ideologies.

"I was someone who believed in overall development and hence I did not come to respect Ms Gandhi's dictatorial style of governance," he says.

He had even, at that time, written to Indira Gandhi asking her not to behave like a dictator during the 1975 Emergency.

Front-runner in fighting multiple social causes

Age is a mere number for Doreswamy who will be called a centenarian next April.

Fighting for the rights of landless and displaced communities is as though part of his DNA.

Frequent hospitalisation and ill health may hinder his social work occasionally, but that's no reason for him to slow down.

In the past three years, Doreswamy has pursued three social causes with utmost dedication.

Firstly, he heralded a team that protested against the dumping of Bengaluru's waste at the Mandur landfills.

"Around 30,000 tonnes everyday was being dumped indiscriminately at this landfill for the past seven years.

"I felt like a criminal about such lack of apathy towards the people living in the surrounding areas.

"Hence, I felt it essential to redeem myself by putting an end to it."

Secondly, he steered the 39-day protest against illegal land grabbing of about 40,000 acre of land in and around Bengaluru.

The AT Ramaswamy Committee report had suggested jail for culprits who had issued bogus title deeds to distribute the land arbitrarily.

After Doreswamy spearheaded the cause, special courts were set up to oversee legislative proceedings in this case.

Lastly, Bengaluru's most loved freedom fighter also led from the front while demanding egalitarian distribution of land to distressed farmers.

"We have lived in poverty for 70 years now.

"And farmer suicides go on unabashedly. It’s not enough to just take the responsibility to feed them; the government needs to figure out a way to make them financially sustainable in the long run.

"In the same context, I threatened to lock down the winter Assembly session in Belguam if a discussion on poverty was not taken up. They had to oblige because it is difficult to not take me seriously," he says.

Doreswamy's definition of an ideal social worker

Ask him who an ideal social worker is and Doreswamy briefly explains in pointers: "Someone who is not materialistic, power hungry, fearful, dependent and revengeful.

"Today's social workers are in search of causes without any conviction to follow through.

"Their one-day protests are mostly for publicity and are not rooted in genuine societal concern. This should stop, we can't win some battles by protesting alone," he concludes.

© 2025

© 2025