Fascinating predictions for the years ahead.

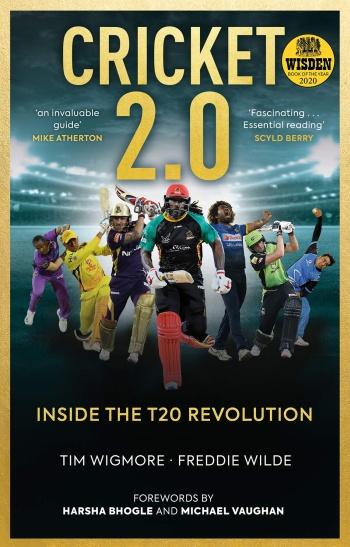

A revealing excerpt from Tim Wigmore and Freddie Wilde's Cricket 2.0: Inside The T20 Revolution on the eve of the IPL 2021 Players Auction.

Teams will be bowled out more, but also make more runs

Many T20 teams still use their resources poorly: In general, they systematically overvalue wickets, meaning that they leave hitting power untapped because they are too cautious for too much of their innings.

The T20 World Cup semi-final in 2016, when India cruised to 192 for 2 off their 20 overs and were then defeated by the West Indies, is a classic of this genre.

T20 sides are still often governed by thinking from 50-over cricket about keeping wickets in hand -- even though this matters far less in T20, whether a side is batting first or chasing.

An enlightening statistic by the ESPN cricinfo writer Kartikeya Date showed that, when T20 teams lost in run chases, they were bowled out just 37% of the time -- half as much as in ODI cricket -- and lost fewer than eight wickets 32% of the time, compared with 10% in ODIs.

This exposed the deep failings in much T20 strategy.

As T20 sides become shrewder, the slow increase in the number of runs per innings in recent years is likely to continue.

Paradoxically, proof of smart thinking may be losing more wickets -- unlike in other formats of cricket, the volume of run scoring and the frequency of wickets being lost could rise in sync.

Rather than build an innings in the conventional way, more teams are likely to use expendable players at the top of the order, like Sunil Narine, to target the fielding restrictions.

Teams will move to more bespoke batting orders, embracing thinking in terms of positions rather than set positions, following on from the examples of CSK and latterly Islamabad United.

The general improvements in the standards of bowlers' batting will augment this shift by giving sides more flexibility.

For instance, teams could have essentially separate batting orders in the Powerplay and afterwards: Two or three low-value players who would be deployed to target the fielding restrictions, followed by players to control the middle of the innings and then those to target the end of the innings.

If a team lost a wicket to be, say, 40 for 2 after four overs, they could send out a player in the team largely in for their bowling to continue attacking; even, say, 12 off six balls while the fielding restrictions remained might be viewed as a good result.

Top order batsmen, who would value their wicket highly during the fielding restrictions and so be likely to begin slowly, could then be saved until after the Powerplay.

This could all help create a paradigm shift in the expectations placed on individual players.

So, rather than top order batsmen aiming to bat for half or more of the innings and sides aiming for at least one member of their top three to score a half-century, teams could be set up looking for, say, any six of the top nine batsmen to score 35 from 20 balls.

Greater emphasis on home advantage

T20 is an inherently volatile game that can be won or lost on the finest of margins.

It is this fragility that means teams should seek to control every possible variable because they could easily end up being the difference between victory and defeat.

If teams can dominate at home and win, say, 70% of their home fixtures, they will typically only require a handful of wins away to progress to the play-off stages.

So far there is only the faintest hint of home advantage in T20: 53% of matches are won by the home team, a lower advantage than in basketball, football or ODI cricket, where home teams win 59% of games.

Yet sides such as Chennai Super Kings in Chepauk, Rajasthan Royals in Jaipur and Perth Scorchers at the WACA have given a glimpse of what is possible.

Perth won 69% of all their matches at the WACA, but their home form then dipped markedly when they moved to a new ground.

As T20 continues to mature it will become more results orientated.

Shrewd team managers will come to prioritise devising a strategy to dominate at home.

Batsmen retiring out

In a CPL match in 2017, just 12 days after hitting an innings of 121 not out, Andre Russell -- one of the most destructive T20 players of all time -- was unused by Jamaica.

Chasing 157 to win against Barbados, Jamaica ended up on 154 for 3, somehow contriving to lose by two runs despite having seven wickets in hand.

Yet Russell did not bat at all -- the T20 equivalent of having Lionel Messi on the bench but not being able to bring him on.

It was a perfect case study of how teams could benefit from retiring out struggling batsmen, rather than allowing them to continue to consume deliveries at the crease and prevent other players from getting to bat.

Retiring a batsman out has negative connotations attached to it partly because cricket is obsessed by the concept of 'fair play'.

Many believe the battle at the crease is part of the game, rather than something that can be tactically ended.

It is not, however, against the laws of the game to retire a batsman out. And, on occasion, it could be prudent for a team to do so, to ensure they didn't leave one of their best batting resources unused.

Match-ups will become more sophisticated

One of the buzzwords of the first era of T20 has been match-ups: That is opposition teams targeting certain types of batsmen with certain types of bowlers.

'It happens every game,' said England's captain Eoin Morgan.

'The one where it has worked best was the World Cup Final in 2016 where we opened the bowling with Joe Root to Chris Gayle. We had an under-par score on the board, we needed early wickets and the ball wasn't going to swing because it didn't swing the first innings so we decided to take a bit of a left-field call and again it was calculated but it came off.'

As data analysis of T20 improves, the level of detail in these match-ups will grow.

Brathwaite hit four sixes off Ben Stokes's last over to ensure England were defeated by four wickets. Photograph: Gareth Copley/Getty Images

Hybrid spin bowlers

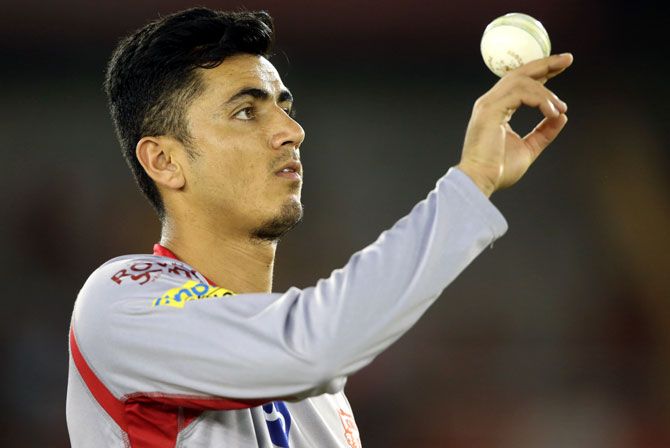

Just as Rashid Khan transformed leg spin, another Afghan teen threatens to transform spin bowling entirely.

Mujeeb Ur Rahman's bowling style is distinctive because it cannot be categorised as either a finger spin or wrist spin.

Mujeeb bowls off breaks, carrom balls, doosras, leg breaks and googlies – he is a hybrid bowler and the first of his kind.

By straddling different bowling techniques, not only is Mujeeb harder to read and has a wider arsenal at his disposal, but he is able to exploit batsmen's weaknesses even more specifically.

The innovation is unlikely to stop there. On October 27, 2018 the Sri Lankan Kamindu Mendis bowled right-arm and left-arm finger spin in the same over in a T20 international against England.

To the right-handed Jason Roy, Mendis bowled left-arm finger spin, taking the ball away from the bat and then mid-over changed to bowl right-arm finger spin to the left-handed Ben Stokes, taking the ball away from the bat once more.

The amount of practice needed to reach an elite standard with both arms is a roadblock to many others doing the same, but Mendis embodies how bowlers will explore new and previously unimagined avenues.

'You need to be constantly evolving,' said Samuel Badree.

'Anything that is different will become successful, at least initially.' As match-ups become increasingly salient in T20, bowlers such as Mujeeb and Mendis are capable of two different styles of bowling and therefore of targeting both right- and left-handed batsmen.

In spin bowling, the smallest changes in grip or release can have profound consequences for how the ball behaves.

Not only will the future involve major shifts in technique such as hybrid spinners and, occasionally, ambidextrous bowlers but the art will continue to become ever more intricate as bowlers push to stay one step ahead of the batsmen.

Super-fast bowlers

Traditionally bowling actions have been a product of a compromise between competing factors -- broadly: speed, accuracy, movement and endurance.

The reduced physical workload of four overs per match and the challenges posed by balls that don't swing and pitches that don't seam, opens up the possibility of a new breed of pace bowler: Concerned almost entirely with bowling at high speeds.

These bowling actions will likely look and feel very different to traditional bowling actions. They will probably be slingy and more round-arm, resembling a javelin thrower as much as a cricket player.

Such bowlers will also be built differently too. They will have distinct training regimes, with high strength and power development emphasised to develop short bursts of explosive movement to attain extreme high ball speeds over 24 balls.

Producing bowlers such as these will require 'a completely different approach to developing fast bowlers' according to Marc Portus, head of movement science at the Australian Institute of Sport and a bowling biomechanics expert.

Cricket has already produced a handful of bowlers in this mould.

The Australian Shaun Tait and the Pakistani Shoaib Akhtar, who played in the early 2000s, are the most famous examples.

Both Tait and Shoaib were clocked at 100 mph and regularly operated in the high 90s.

Tait and Shoaib employed bowling actions with enormous pivoting delivery strides and a slingy, round-arm release that echoed the Australian Jeff Thomson in the 1980s who was also capable of electric speed.

Both Tait and Shoaib battled injuries throughout their careers: The sheer physical burden placed on their bodies by their bowling actions was too much to withstand bowling more than a dozen overs at a time. In T20 though, with only 24 balls permitted per bowler, this barrier no longer exists.

Batsmen more like baseball hitters

The emphasis on boundary hitting in T20 will give rise to a new subset of batsmen, more aligned to baseball hitters than traditional cricketers.

These players will have techniques designed to maximise shot power and distance with minimal footwork and a strong, stable base and a still head.

Their bat swing will be long and clean and they will generally be big, powerful men. They will typically target the leg side because it is the most natural hitting zone but they will evolve to hit over the off side as well.

'I think guys are going to get bigger and stronger like baseball where the fielders don't matter,' envisaged Brendon McCullum.

'You'll just take the fielders on. Andre Russell is like that, isn't he? He doesn't play sweeps or ramps, he just hits in his area.'

Spinners will bowl more

The great CSK and KKR teams have already shown what is possible by building spin-heavy attacks, particularly in spin-friendly conditions; so have the CPL's Guyana Amazon Warriors.

Gradually more teams will break with convention and seek to take advantage of this fundamental imbalance between pace and spin.

Teams who are set up to deliver at least 16 overs of spin -- especially in home conditions – will become commonplace.

One team may even make history by delivering all 20 overs by spin.

Spin power hitters will be very valuable

The continued rise of spin bowling and its greater usage will place huge value on those batsmen capable of power hitting against spin.

The lack of pace on the ball and the different directions of turn have traditionally made consistent hitting of spin bowling very difficult.

Yet the likes of India's Hardik Pandya – with long levers and rapid hand speed – have shown that it is possible.

Until spin power-hitting techniques become a more established part of youth coaching, these players will remain very rare and very valuable.

Batsmen will start faster

The first era of T20 batsmanship was defined by batsmen expanding their power game, by elevating strike rates from around 130 towards 150.

The next era will be defined by batsmen reaching these scoring rates more quickly.

Currently many batsmen still take time to 'play themselves in' -- an approach embodied by Chris Gayle who scores very slowly at the start of his innings before accelerating rapidly later.

Higher scoring rates, deeper batting orders and the evolution of the format more generally will place pressure on this approach and greater emphasis will be put on the need for batsmen to start more rapidly.

The signs of improvement are already there: Strike rates in the first ten balls of the innings rose from 105.83 between 2010 and 2015 to 112.41 since then.

Excerpted from Cricket 2.0: Inside The T20 Revolution by Tim Wigmore and Freddie Wilde, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025