Would there have been an incomparable batsman named Sachin Tendulkar had Doordarshan not telecast Guide one summer afternoon?

A fascinating excerpt from Abhishek Mukherjee and Joy Bhattacharjya's must-read book, The Great Indian Cricket Circus.

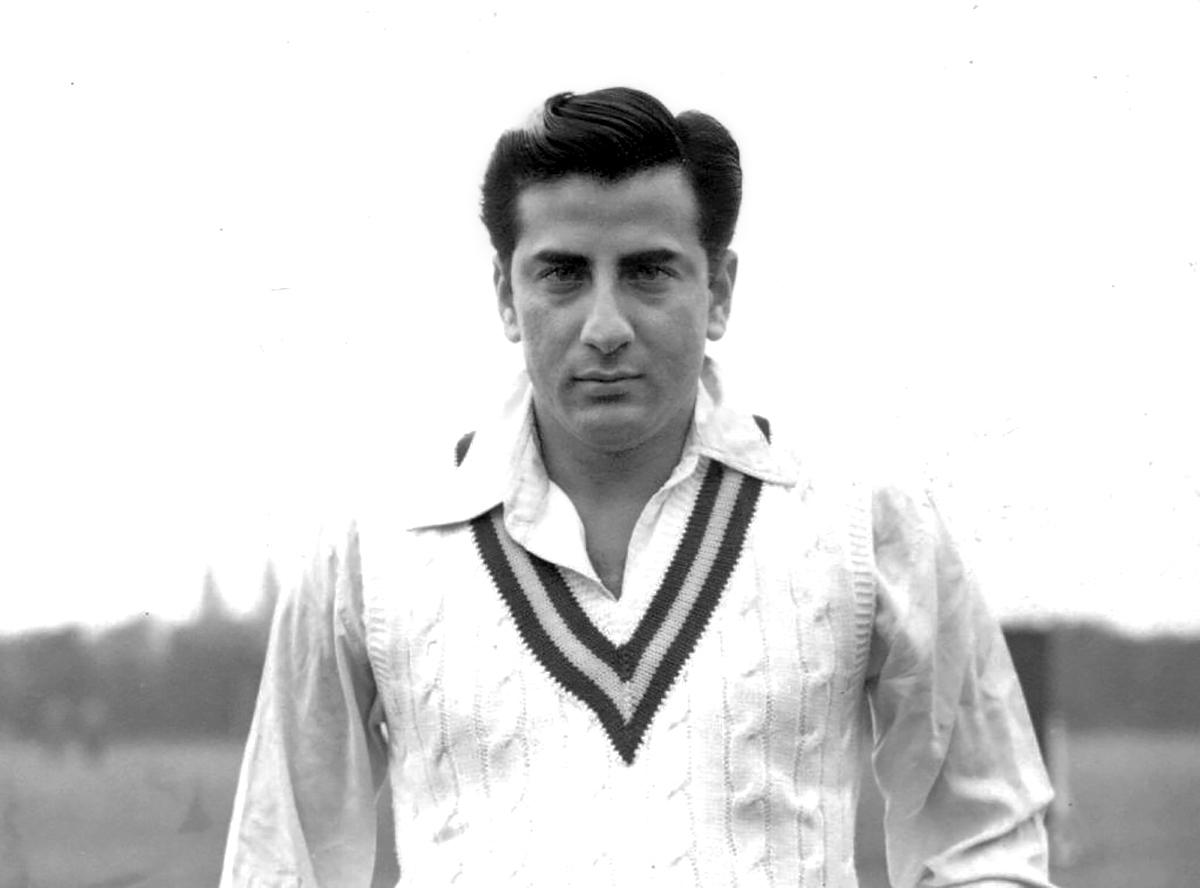

FAZAL ATTACKED ON TRAIN

India were to visit Australia in late 1947 for their first cricketing tour after Independence.

The pre-tour camp was held in Poona from 15 August 1947.

Fazal Mahmood, twenty, was supposed to attend the camp, but a full-fledged curfew had been imposed at Lahore in the aftermath of religious riots.

He travelled to Karachi by road before flying out to Bombay. He made it to Poona.

The camp concluded without much fuss. The cricketers took the train back to Bombay.

A mob attacked this train with the intention of lynching the Muslim cricketers. C K Nayudu, then fifty-one, stood between the rioters and Fazal with a cricket bat.

Fazal reached Bombay safely, abandoned his original itinerary (via Delhi), and flew straight back to Karachi.

He did not tour Australia with India. Instead, he became Pakistan's first great fast bowler.

It took him five years to return to India -- as the spearhead of the opposition's attack.

He took 12 for 94 to help Pakistan win the second Test at Lucknow.

Indian cricket of the 1930s was mostly dominated by pace, with Mohammad Nissar, Amar Singh, Jahangir Khan and even an ageing Ladha Ramji calling the shots.

Fazal would not only have carried on that legacy but also inspired a generation after him, like Kapil Dev did in the 1980s.

As things turned out, no Indian fast bowler was able to take 100 Test wickets until Kapil in 1979/80, and the lack of fast bowlers meant that India seldom won Test matches outside the subcontinent.

WADEKAR GETS NEW SHOES

By the early 1970s, Bombay winning the Ranji Trophy every year was as inevitable as death and taxes.

Having won fifteen titles in a row, they were set for a sixteenth when they met Karnataka in the semi-final of the 1973/74 season.

Karnataka made 385 in the first innings, but Bombay cruised to 179/2 by stumps on Day 2 with Ashok Mankad and Ajit Wadekar at the crease.

Wadekar was wearing new rubber-soled shoes. He had been comfortable in them while batting in the nets -- but net practice does not involve running between the wickets.

Soon after play began on the third morning, Mankad played Karnataka Captain E A S Prasanna to point.

As Sudhakar Rao sprinted in to pick up the ball, Wadekar called for a run, but Mankad sent him back.

Wadekar had an eternity to return to the crease, but the new shoes let him down.

He slipped, and could not make it back in time. Prasanna did the rest.

Bombay collapsed to 307. Karnataka won on first innings lead and advanced to the final. Bombay's streak had come to an end.

A vengeful Bombay won the next three seasons, but Prasanna's Karnataka had shown the rest of India that Bombay were not invincible.

Every now and then Karnataka posed a threat, and by the end of the decade Delhi too became a force to reckon with.

Bombay remained the best side, but it was no longer a monopoly.

KAPIL DENIED FOOD

In 1975, a young Kapil Dev was attending a camp for budding cricketers at the Cricket Club of India in Bombay.

After a gruelling session in sultry heat, the youngsters were served a meal of two dry chapatis and vegetables.

A famished Kapil demanded more. When he was told that the instructions had come from Keki Tarapore, administrator of the camp, Kapil led a small group to Tarapore's office.

Kapil was blunt: 'Nobody can fill his belly with such a small serving, and I am a fast bowler. I practise a lot and really sweat it out. That's the reason...' Kapil never forgot Tarapore's response. 'Young man, India has been playing international cricket for over forty years, but till date India hasn't produced a single fast bowler. Fast bowler ... that's the best joke I've heard in years!'

The man who led India to their first World Cup victory, broke the stereotype of Indian cricket being dependent on batting and spin bowling forever and inspired generations of fast bowlers, has always cited Tarapore's reaction as a motivation behind his cricketing career.

SALVE DENIED PASSES

Two significant events at Lord's in June 1983 changed the course of Indian cricket forever.

While the more famous one took place on the field -- India beat West Indies in the final to win the World Cup -- what happened just outside was no less significant.

N K P Salve, BCCI President at that time, had requested the authorities for two extra passes for the final.

When that was denied, a humiliated Salve vowed to bring the World Cup Championship out of England.

Until then, England had hosted all three editions of the tournament: Salve set out to change that.

Along with representatives from Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Singapore and Malaysia, Salve founded the Asian Cricket Council, and in 1984, the ACC hosted the inaugural Asia Cup, thus becoming the first regional organisation to host international cricket and generate profit.

Unlike Kerry Packer's World Series or the Rebel Test matches in South Africa, the Asia Cup was an official competition in which cricketers could participate without fear of being banned.

That same year, in the ICC meeting, Jagmohan Dalmiya and I S Bindra secured enough votes to fulfil Salve's vow: India and Pakistan co-hosted the next World Cup in 1987, thereby laying the first stone towards India's dominance in world cricket off the field.

DOORDARSHAN TELECASTS GUIDE

One Sunday evening in 1984, Doordarshan telecast the classic Dev Anand starrer, Guide.

While the residents of Sahitya Sahawas Colony, Bandra, Bombay, sat glued to their television sets, three boys -- unil Harshe, Avinash Gowariker and Sachin Tendulkar -- climbed a mango tree.

During their pursuit, a branch gave way and all three fell with a crash.

The boys received some 'treatment', but the Tendulkar household went a step further.

The family decided that something had to be done about young Sachin's pent-up energy, especially during the long summer vacations.

Ajit Tendulkar, his brother, recommended Ramakant Achrekar's cricket coaching camp. The rest is history.

LAMBA'S INJURY

The Karachi Test match of 1989/90 boasts two of the most significant incidents in the history of Indian cricket.

One was Sachin Tendulkar's debut. The other took place not too long before the toss.

By the late 1990s, much of Mohammad Azharuddin's initial shine had worn off.

Having gone almost three years without scoring a Test hundred, he was on the verge of being dropped from the side. In the Karachi squad Azharuddin would be the 12th man.

Just before the toss, Raman Lamba, who had scored the most runs for India in the recently concluded Nehru Cup, reported a finger injury.

Azharuddin played instead, scored 35 in each innings, and took five catches, some of them spectacular.

In the next Test match, he scored 109. He was back. Lamba would never play Test cricket again.

India drew the series 0-0. A few days after the squad returned, Raj Singh Dungarpur, then chair of selectors, approached Azharuddin during a domestic match: 'Miyan, kaptaan banoge?'

Azharuddin had led only four times in first-class cricket until then, two of these were after the Pakistan tour.

He agreed, and went on to become one of India's longest-standing, as well as controversial, captains.

Indian cricket in the 1990s was, thus, shaped by the injury of a man who did not play for India in the 1990s.

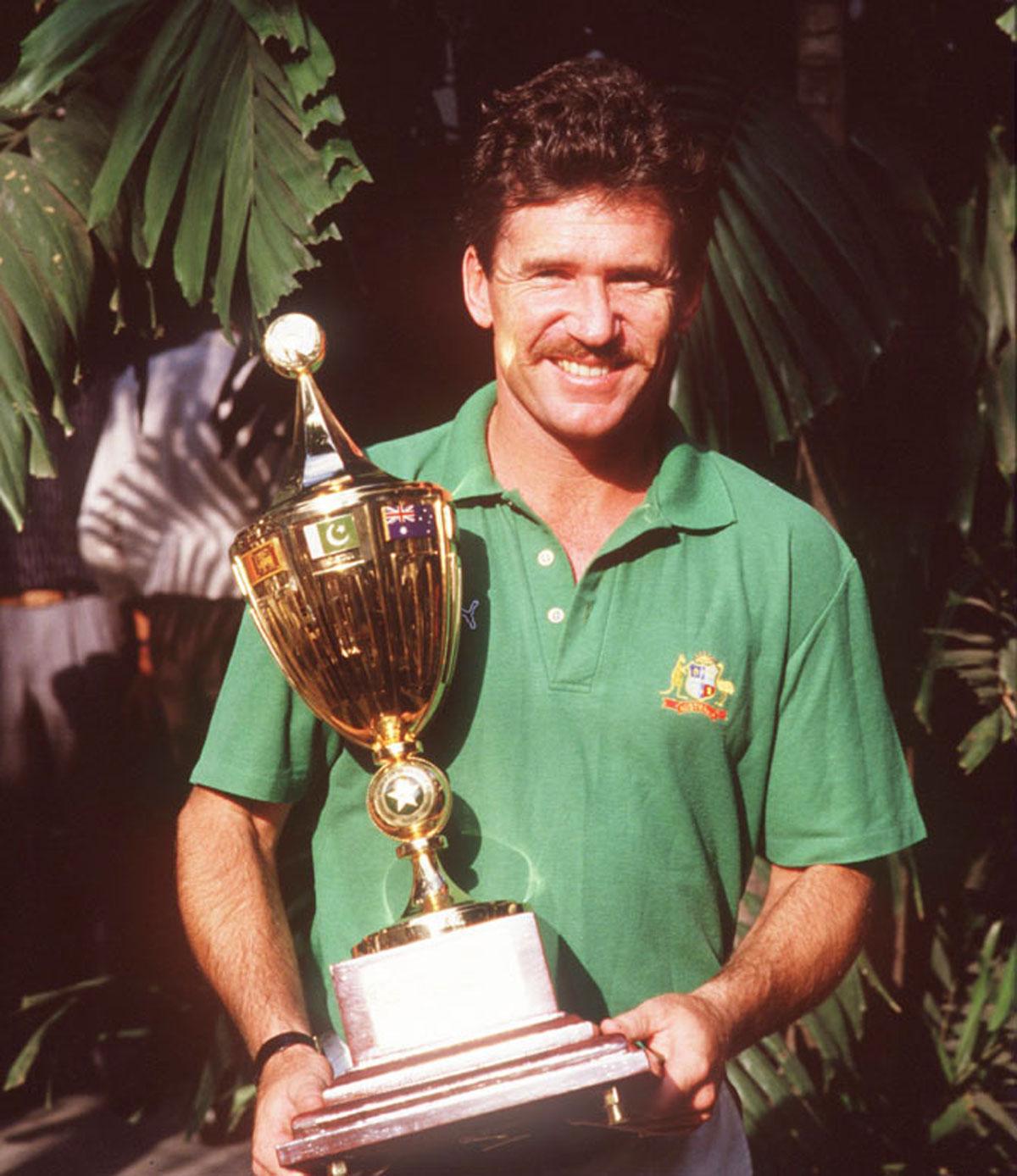

SOUTH AFRICA RETURNS

South Africa's apartheid policies had earned them a ban from international cricket for almost two decades.

However, throughout the 1980s, Ali Bacher -- the last man to lead South Africa before the ban--tirelessly tried to arrange 'rebel' tours, inviting teams to South Africa, luring them with enough money to forego their international careers.

South Africa's first international series after the ban was in India, in 1991/92.

Bacher, manager of this team, asked the BCCI about the formalities regarding broadcasting rights of the series in South Africa.

This seemingly normal request left the BCCI authorities confused, for never in their history had anyone offered them money to telecast live cricket.

BCCI's revenue from cricket matches in India came only from a share of stadium tickets and advertisements inside the stadium.

If anything, at times they had had to pay Doordarshan to cover live cricket (and not the other way round).

After a frantic discussion, the BCCI got back to Bacher with an offer of USD 10,000 per match for the three ODIs.

Bacher offered USD 40,000 per match (in other words, four times what the BCCI wanted for the entire series).

South Africa's return to international cricket mattered to the people back home, whose future leader Nelson Mandela would later say, 'Sport has the power to change the world.'

This sum of USD 120,000 for a high-profile series was the BCCI's first income from selling television rights.

For perspective, the BCCI sold the IPL rights for five years to Disney Star and Viacom for USD 6.2 billion in 2022.

SIDHU HAS A STIFF NECK

On the morning of 27 March 1994, Navjot Sidhu woke up with a stiff neck in his hotel room in Auckland.

India had an ODI that day against New Zealand, but now Sidhu was ruled out.

Who would replace Sidhu as Ajay Jadeja's opening partner? There was no reserve opener.

A young Sachin Tendulkar volunteered. He even promised coach Ajit Wadekar that he would never repeat the request if he failed. He slammed a 49-ball 82 and never looked back.

Until that point, Tendulkar had scored 1,758 runs at an average of 30.84 with a highest score of 84.

He would amass another 16,586 at 46.98 with 49 hundreds to finish as the most prolific run-scorer in ODI history.

Tendulkar the opener was born, and he grew with satellite television in India.

So prolific would his run-scoring be that by the end of the decade he would earn the moniker 'God'.

AND FINALLY ... THE ONE THAT COULD HAVE, BUT DIDN'T!

On 10 July 1949, Narayan Masurekar was visiting a Bombay hospital to meet his nephew, who was born earlier that day.

He noticed a tiny hole near the top of the left earlobe of the baby. When he returned next day, to his horror, the hole was no longer there!

Upon a frantic search, the infant Sunil Gavaskar was found 'sleeping blissfully' next to a fisherwoman.

The babies had been swapped accidentally when they were being bathed.

Had Masurekar not noticed, India might not have got their first legendary batter -- at one point Gavaskar had the most Test runs and hundreds in the world -- for decades.

Worse, generations of batters would probably not have been inspired by a living legend.

Although, given Gavaskar's dedication, determination and discipline, India might have become the global leader in fishing!

Excerpted from The Great Indian Cricket Circus by Abhishek Mukherjee and Joy Bhattacharjya, with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025