The hiring of Ronojoy Datta as the airline’s CEO - done primarily by Bhatia himself - may have been one of the two factors that marked the end of a relationship that was already beginning to fray.

Many also suspect that the final nail in the coffin was the $ 20 billion CFM engine deal brokered by Bhatia that left Gangwal out entirely.

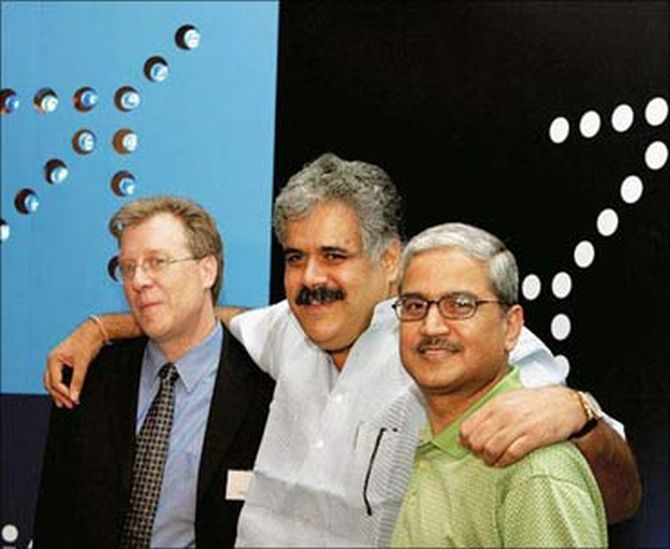

In the first of a two-part series, Anjuli Bhargava, throws light on the developments that led to the bitter public spat between - Rahul Bhatia and Rakesh Gangwal - the two promoters of IndiGo - India’s largest airline.

In August 2018, Rahul Bhatia received an email from Rakesh Gangwal, his co-founder at IndiGo, business partner and a long-time friend, which stated the latter’s inability to be involved in the company’s day-to-day matters as he now had more important issues to focus on.

Gangwal had been watching the operations at IndiGo for over a year and dismissing certain lapses in governance as “inadvertent”.

He had also been raising his concern about related party transactions (RPTs) that the airline had entered with his partner’s parent company (InterGlobe Enterprises or IGE).

But the only answers he got were: “We’ll look into it”, “Don’t worry about it”, “We’ll make sure” and so on.

Finally, in August last year, Gangwal decided that he had had enough and that he needed to call Bhatia out.

His August email triggered a chain of events that has eventually resulted in his seeking the intervention of Sebi and bringing the issue to the notice of the entire country, including the Prime Minister.

His plea to Sebi and Bhatia’s response are now public documents that highlight what an ugly turn the spat between the promoters has taken.

The IndiGo stock fell sharply in response, eroding value and leaving many small shareholders a lot poorer.

How did things come to such a pass?

By all accounts, till July 2018, the relationship between Bhatia and Gangwal was on an even keel.

The decision to ask the airline president and CEO Aditya Ghosh to step down in April 2018 was a joint one - both the promoters agreed that he needed to be replaced for a variety of reasons.

Similarly, the decision to bring in Greg Taylor, who had spent three decades at United Airlines, as CEO designate was a joint one.

Bringing in young blood from overseas to New Delhi had become a challenge due to the variety of problems faced by expats.

Taylor, who is in his 60s, was more of a compromise appointment, but he was a familiar figure, having had two stints with the airline over April 2016 to January 2018.

So, he was brought in again in May 2018 to replace Ghosh, a gambit that failed, as his December departure confirms.

Meanwhile, by end 2017 and early 2018, IndiGo was growing faster than envisaged.

Its fleet comprised almost 170 aircraft and the existing team’s inability to manage the pace of growth was beginning to show.

The problems with the Neo engine were still niggling and safety concerns plagued the carrier.

Moreover, in late 2016 and early 2017, on-time performance - its main USP - had taken a beating.

Through 2017, the airline’s brand image also took a knock because of the rude and arrogant behaviour of the staff, which, many felt emanated from the very top.

IndiGo had become bigger and more successful than imagined, and many of the senior management were basking in that glory.

President and CEO Ghosh, in particular, is said to have begun to feel invincible and his arrogance percolated down the line.

In fact, there were times when he did not respond to promoters’ emails and questions.

This didn’t go down well, although there were other matters, too, that led to his exit.

But even as the airline continued on its upward trajectory, the two promoters had their feet firmly on the ground.

To ready the airline for its next phase of growth, a joint decision was taken to induct more talent from overseas - albeit retired or executives working from home on consultancy assignments (the IndiGo old guard refers to them less charitably as “idle”) - at extremely attractive pay packages.

These packages were often 10 times more than what was being paid to the Indian incumbents who had been at it for anywhere between five and ten years.

After Taylor came in, he started to build a new team at the airline.

Michael Swiatek, an executive from Chile’s LATAM, was brought in as chief planning officer, William Boulter, an executive from TAAG Angola airlines, was made chief commercial officer, Cindy Szadokierski was brought in as vice-president of airport operations, and Scott Brandt as vice-president of corporate planning and analysis.

In May 2018, Wolfgang Prock-Schauer, then CEO of Go Air, was inducted as the airline’s president and chief operating officer after both the promoters met him in Mumbai.

The result was that Sanjay Kumar, the airline’s chief commercial officer and an IndiGo loyalist, and Sanjeev Ramdas, executive vice president and a Bhatia loyalist for 13 years, were rendered redundant.

Ramdas hung on, but Kumar submitted his resignation in June 2018.

Bhatia, who values and rewards loyalty, tried to retain him by offering him a post in the parent company IGE, but Kumar refused the offer.

In effect, in a matter of 3-4 months, there was a brand new team at top, several of whom had very little experience in the Indian environment and were not at the peak of their careers.

However, on paper, everything seemed fine.

After all, the airline was growing and needed to shore up its management team.

Handling a fleet of close to 200 required exceptional skill sets.

For instance, an expensive Sabre system to manage routes and scheduling that the airline had acquired was not being used to its full potential as those in charge at the time were unfamiliar with it.

In the past too, IndiGo has had discord over hires, but it was nothing they couldn’t tide over.

In 2017, when the airline decided to add ATRs to its fleet, Gangwal was convinced that the man to do the job was Shakti Lumba, former Indian Airlines stalwart and IndiGo's own former VP for flight operations.

Lumba, who was not on the best terms with Ghosh, was hired for all of two days.

After issuing a public release, Ghosh and Bhatia terminated Lumba’s contract on the grounds that DGCA had raised objections to his appointment.

It remains a matter of speculation whether the call Ghosh claims to have received from the DGCA actually came.

Gangwal was not happy with this and expressed as much to the duo, but eventually he went along with the decision.

These details establish the fact that as late as July 2018, the two promoters seemed to be by and large in sync with each other.

Yet by August, things had deteriorated to such an extent that Gangwal sent his email announcing his withdrawal from the airline’s day-to-day operations.

Although many believed that Gangwal’s contribution to the airline was restricted to aircraft purchase negotiations, he was actually far more involved.

Macro strategy, route planning, important management hires were all part of his domain.

He also came to Delhi every month besides spending a large proportion of his time in the US on IndiGo matters.

Combined with the new mistrust (details in Part 2) that had crept in between the partners, it didn’t help matters that almost all the foreigners who were brought in to manage the growing carrier either underperformed or simply failed to fit in with the airline’s culture.

Many Indians resented being told what to do by their “idle back home” bosses.

Often, the juniors gleefully watched their expat boss make a mistake and did not bother to correct him as “he’s the boss, he should know better”.

In the process, the company suffered.

This showed up in the airline’s performance, and the first two quarters of 2018 produced very poor results.

Quarter three was marginally better, but that was primarily due to Jet’s grounding, which proved to be a windfall for the carrier.

In addition, the airline faced a spate of cancellations right from end 2018 to April 2019 due to its poor pilot management, always a weak spot for IndiGo.

In general, Bhatia had always acceded to Gangwal’s wisdom and experience when it came to the hiring of top management.

Candidates were often found by Gangwal and taken on board by Bhatia.

Many in the company were of the view that Bhatia often “succumbed like a lamb” to Gangwal in matters like this, in the belief that his partner knew best.

Both were confident that each man was acting in the company’s best interests and gave each other the space to do what they did best.

Bhatia had, however, managed to keep Ghosh in the pilot’s seat for far longer than Gangwal would have liked.

After Gangwal’s withdrawal from the company’s day-to-day affairs, Bhatia took firmer hold of the reins.

Although Taylor was CEO designate, by December, Bhatia decided to bring in Ronojoy Datta as the airline’s CEO, rendering Taylor redundant.

This decision didn’t have the stamp of his partner and many feel that it did not go down well with Gangwal.

The entry of Datta and the departure of Taylor led to a second churn at the airline - the first had happened around the time Ghosh and Kumar quit.

A lot of the expats left and the contracts that had ended were not renewed.

Many argue that Gangwal, who was accustomed to his partner acquiescing to his choices, did not like the fact that Bhatia was beginning to flex his muscles.

The hiring of Datta - done primarily by Bhatia himself - may have been one of the two factors that marked the end of a relationship that was already beginning to fray.

Many suspect that the final nail in the coffin was the $ 20 billion CFM engine deal brokered by Kiran Rao (formerly with Airbus, who was working on a consultancy basis for Bhatia) and assisted by Riyaz PeerMohamed, chief aircraft acquisitions and financing officer at IndiGo - a deal which left Gangwal out entirely.

The move was a loss of face for Gangwal, who had supported the P&W engines that were likely to result in more fuel savings in the long run.

After a rocky 2018, operationally, things have stabilised at the carrier.

Barring pilot management, which remains a niggling issue, on-time performance has picked up.

Cancellations are low and the planes are full.

The grounding of Jet has helped improve yields and the profitability of the airline (and that of its rivals).

Perhaps the last thing IndiGo needed at this juncture was the outbreak of a bitter spat between the two promoters.

But that is where it finds itself.

© 2025

© 2025