Mukund Rajan, who worked closely with Ratan Tata, recalls the unique experience of working with the corporate titan.

As the first year of induction drew to a close and one had to be placed in a Tata company, I received a call from S Ramakrishnan, asking me to meet Ratan Tata.

I had an inkling that this might be connected with a job offer and was relieved when I was told that I should first introduce myself to the chairman's executive assistant, a Tata Administrative Services officer named Rajiv Dube, before I met the chairman himself.

I felt Rajiv would be able to give me tips on how to conduct myself at the meeting with Ratan Tata.

But on the appointed day in December 1995, I walked into the chairman's office on the fourth floor of Bombay House and ran straight into Ratan Tata.

He immediately ushered me into the small conference room, so there was no preparation for the interview, no sense from Rajiv as to how I should conduct myself and no guidance on whether I should ask any questions of the chairman or just listen to him.

But the meeting turned out to be quite interactive and very cordial and pleasant.

Ratan Tata asked me how I had spent the year of induction and then mentioned the role in his office as that of executive assistant.

I was to help Rajiv assist Ratan Tata, as a precursor to taking over all the responsibilities that Rajiv was then discharging.

On hearing that I was to be the chairman's executive assistant, I felt it but fair to point out to Ratan Tata that I had not done an MBA and had very little business-related experience.

His answer will remain etched in my mind -- all I needed to succeed in the corporate world, he said, was 'good common sense'.

He emphasised the responsibility one would carry as part of the group chairman's office -- this office would be the court of final appeal for many Tata stakeholders with grievances, and one would be tasked to live up to their expectations, right from acknowledging receipt of their communications to finding solutions for them.

He underlined the importance of humility and the need to show empathy in dealing with these stakeholders.

Ratan Tata went out of his way to make me comfortable and I left the meeting relieved but also inspired to work with this man.

***

The first day I strode into the Tata headquarters at Bombay House as the latest addition to the office of the group chairman, it struck me that I was stepping into a huge piece of history, with the opportunity to actively participate in shaping its future.

Bombay House, designed by George Wittet, who also designed the famous Gateway of India, is one of the buildings in the heritage centre of Mumbai, in the Fort area.

Its very imposing façade was somehow diminished as a result of a small and relatively nondescript entrance.

But this thick stone-walled ground-plus-four-floors Edwardian structure accommodated several hundred employees from all the major Tata companies.

Most of the offices were plainly furnished, the exception being the carpeted corridors of the fourth floor, which housed both the boardroom and the group chairman's office, and on whose walls hung paintings of a number of modern Indian masters.

The group chairman's office has moved around on the top floor; in J R D Tata's time it used be the corner office to the far end on the left when entering the floor from the lift.

Ratan Tata, however, occupied this office for only half his tenure as group chairman, preferring during the first half to continue using the office he had occupied as chairman of Tata Industries.

Before joining Ratan Tata, I made one small faux pas. I asked for special leave to finish the edits sought by my editor at Oxford University Press India on my soon-to-be released book.

I received grudging approval for eight weeks' leave, thanks to Rajiv Dube's intervention.

He assured the chairman that he would carry the office load without any difficulty till I joined.

When Global Environmental Politics was finally published, I gifted the first copy to Ratan Tata.

With his typical eye for detail, he noticed and joked about the weak binding of the book, and then congratulated me on becoming an author.

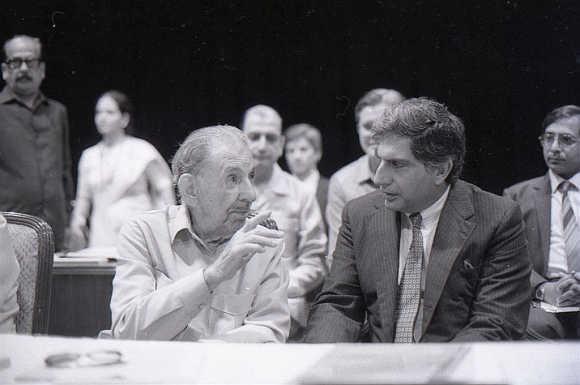

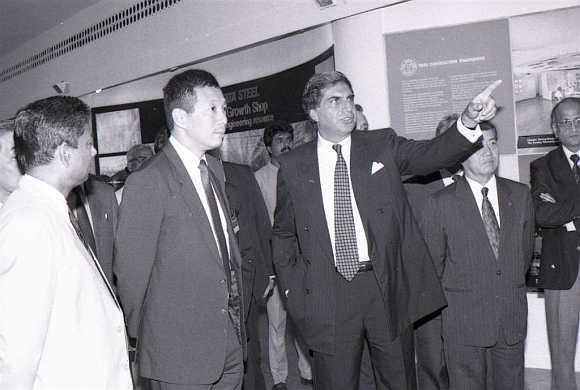

The Ratan Tata whom I saw for most of the next twelve years that I spent in his office was a delightful personality.

At well over six feet in height, with wide shoulders and a broad frame, he had a formidable presence.

In office, he would always be immaculately dressed in sharply cut fine suits (the only exceptions being weekends, when he would occasionally pop in wearing shirts and khaki trousers), and carried himself with grace.

He was extremely grounded and well spoken, and in all my years with him I probably heard him raise his voice only on a couple of occasions.

He gave his staff a great deal of autonomy, and to have that at a young age was hugely empowering for me.

He was extremely friendly for the most part, but you could sense when he was displeased from the coolness or even coldness he could convey.

The things I liked best about Ratan Tata were his ability to laugh loudly and his incredible mimicry of his colleagues.

These were the times when he was most lovable, and even senior colleagues otherwise known for their reserve and aloofness would warm to him despite themselves.

He would doodle during long meetings, and once drew the bald heads of three senior Tata Sons directors, Shahrokh Sabavala, Jim Setna and Noshir Soonawala, viewed from the back.

They all had a hearty laugh when he showed them his work, and Ratan Tata was so pleased that he gifted each of them prints of the drawing, titled 'The Three Ss'.

On another occasion, Ratan Tata and Farokh Kavarana, having quietly kicked Jamshed Bhabha's shoes to the far corner of the august Tata boardroom, were sharing a chuckle.

Bhabha, who was getting along a bit, used to slip his shoes off his tired feet and place them under the table.

He was singularly distressed after the meeting when his colleagues started filing out of the boardroom and he was unable to find his shoes!

I once even had to restrain Ratan Tata from planting a very life-like green plastic snake in the recess of the chair Jamshed Bhabha used during the board meetings of Tata Sons -- I was worried lest the senior citizen be frightened into a heart attack!

In 2002, we planned a quiet dinner to celebrate the successful resolution of a spat with the central government and then telecom minister, Pramod Mahajan, over some decisions taken by the long-distance telephony operator, Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited after its privatization.

Senior Tata Telecom executive N Srinath, Niira Radia (head of Vaishnavi Communications, the agency which held the Tata public relations mandate at the time) and I met at the Grand Maratha hotel near Santa Cruz airport.

Ratan Tata had decided to drive himself to the hotel, which is at the other end of Mumbai, from his home in Colaba -- not a brilliant idea in Mumbai traffic.

When a weary Ratan Tata arrived at the restaurant we had picked, it turned out that the place was showcasing foreign belly dancers.

A reticent man, used to keeping a low profile in public, he was terribly embarrassed when curvaceous dancers with ample bosoms made their entry.

One of them even tried to persuade him to stand up and dance with her and he had to vigorously reject her entreaties.

Niira and I, however, decided to be good sports and joined the dancers on the dance floor, leaving Ratan Tata to settle down to a conversation with Srinath that looked somewhat boring from our end.

By the time the food arrived, Ratan Tata had lost his appetite and could not enjoy the spread, while the rest of us tucked in with gusto.

Finally, capping an altogether unhappy evening for him, his credit card failed to function at the restaurant, not an unusual problem in those days.

As the host, he could not ask the other three in his party to lend him money; fortunately, the restaurant manager had recognised him by then and volunteered to send a staffer to Bombay House the next day to collect the payment!

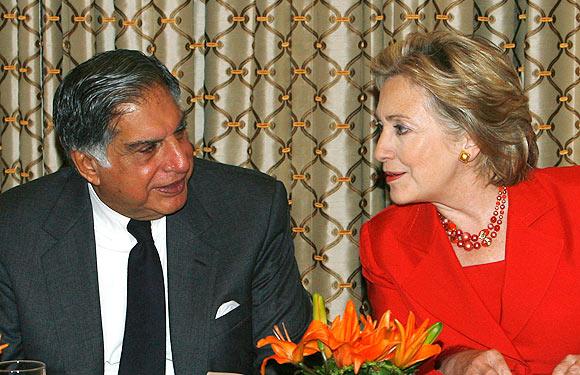

In the years to come, and certainly after I left his office in 2008, the Ratan Tata I first came to know and appreciate became increasingly invisible.

He was replaced by a senior statesman with a larger-than-life figure.

Most of his colleagues came to be intimidated by his personality and stature. And the woes that were visited upon the Tata group, particularly the 2008 terror attack on the Taj, the financial struggle in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the so-called 2G scam and its fallout, took their toll on this essentially decent, fair and fun-loving human being.

Excerpted from The Brand Custodian: My Years With The Tatas by Mukund Rajan, with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.

© 2025

© 2025