'What's sad today is that there are so many people who cannot find work, not because the country is devoid of that opportunity, but because we are not doing enough in the country.'

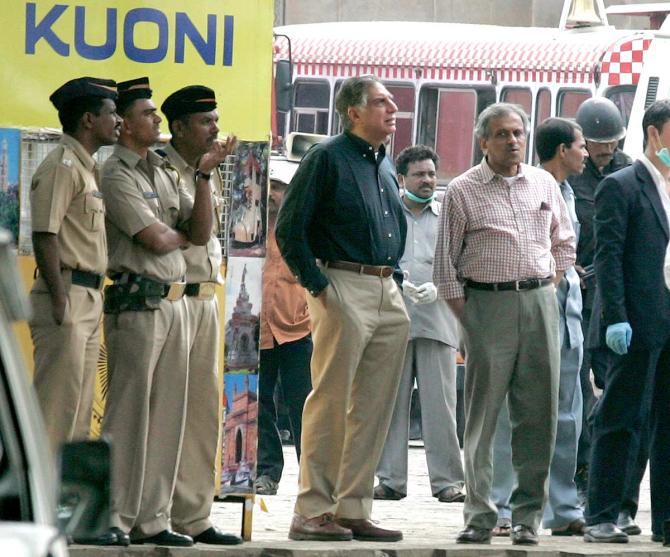

Interview with Ratan Naval Tata, interviewed by Tarun Khanna, Mumbai, India, April 27, 2015, Creating Emerging Markets Oral History Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School, with the kind permission of the Harvard Business School.

Mr. Tata, thank you very much for taking time to do this Creating Emerging Market interview series with us. I'd like to start with a very broad question, if I may.

As you reflect on the years that you had formal stewardship of the Tata Group, can you recall one or two pivotal moments when you thought the direction of the Group changed, either in a positive way or perhaps in a less than positive way?

There are probably several moments. Perhaps the best way to answer that is to talk my way through the start.

There were two or three things that I inherited in the Group that Mr. J. R. D. Tata handed over to me.

One was a Group that was high in ideals, and values, and ethics, which I tried very hard to, and hopefully succeeded in, retaining; but also a Group which had a board of directors that may have been in their 80s or close to that age, many of them unable to walk unassisted into the board room.

Some very hard of hearing, some not staying awake through the meetings, but all rising to the occasion to not allow a change to take place, whatever you may have wanted it to be.

As I had looked at the Group before being its chairman, what seemed to me necessary was that the Group be more nimble footed, more consumer oriented, and be willing to take risks in getting into new businesses.

We were now in 1990, and the whole digital revolution was just starting to hit India.

There was the removal of all the licensing and tremendous opportunities, and I did not want to be thwarted by people who said this would never be possible.

One recollection that I have is of a Group that is venerable in many ways, but unwilling to change and very staid in its traditions, etc., which I thought needed to change.

The other recollection was the concerns I had how to operate in a country where the ethical fabric was deteriorating, and what a major force like J. R. D. Tata could have done to stand up and fight this.

Could a new guy coming along and fight with the same vigor, or might it destroy whatever one was trying to do? In that sense, this had a bearing on how one chose to act.

I made a public announcement when I took over that we would rationalize the Group, condense it into more core businesses, and restructure it by getting rid of some of the companies that were irrelevant, etc.

One recollection I have is we had a soap company, Tata Oil Mills. It had gone from, I think, something like a 20 percent market share to 2 percent market share.

It was heavily in loss, had no new products, and it seemed to mean obvious one to find a solution for and get it off our hands.

I thought I had an ideal and a dignified solution to sell it to Hindustan Lever, our major competitor. The shareholders would get a good share, a good stock to hold onto.

We had a stand-alone agreement that no employee would be touched for three years -- no distributor or supplier would be touched for three years.

It seemed like a very nice settlement as far as we were concerned.

It seemed like the gods just descended on me from all sides, because the stock market went for me, the media went for me, our manpower went for me -- and people just thought that I did the most dishonorable thing.

After that, my public utterances of rationalizing sort of disappeared. If they did take place, they took place very quietly, and so that's something else I remember.

If I can ask you a couple of questions about that: I remember the jettisoning of, or the attempted jettisoning of, that asset. You obviously wanted to do right by your stakeholders in that business, therefore negotiating the no letting go of employees and things of that nature.

Could you have even gotten a better deal if you had not bothered with those sorts of things?

No, I don't think we could've gotten a better deal, because this was a share swap.

If it had been a cash transaction, there would've been even fewer players in this, and a stock swap with a major company was a good thing for the shareholders.

But you were doing the right thing for the employees and distributors and so on; it didn't seem to be sufficient?

Well, it was just tremendous emotion because it was a company with second-generation employees. Suddenly, everybody got patriotic.

It's like losing your country to another country who wins you over. You have failed -- you have surrendered, if you will, to the bigger force, which in this case was your sworn enemy.

You had fought him in the marketplace for years; and then you always have a blame game.

The management is responsible, the employees are responsible -- each one blaming the other, and there's one new guy that came along and decided to do this.

We had been in business for X number of years, X decades. My father had been the managing director of that company, so that certainly was one very memorable kind of area.

I don't think there is anything else that I can think of that stands out as much as that in my early days.

There were progressions that took place thereafter, but I think they were more evolutionary.

Maybe we can fast forward to when you had settled in and had won your spurs and your credibility within the organization, something that you tried to do that, in retrospect, was both especially fulfilling or perhaps equivalently distressing, as the case might be.

Something momentous that you tried to pull off in the middle. We're trying to learn from epochal instances. Perhaps one of the globalization moves?

OK. In the years that India opened up, we also had an economic downturn, initially -- I think in '89-'90, in that timeframe.

When one was in that, your market share may have remained intact, but the market shrank.

Volumes went down -- companies that were otherwise profitable were now really struggling, and you were in the midst of changing some of the metrics -- operating metrics -- that you had in the company. And you wondered whether you had a bit of the hockey stick syndrome, where you were at the base& of your sales and could look like you were in great peril.

One thing that struck me at that time was the fact that you were dependent on one economy, the Indian economy.

You wondered whether you should try and change that. That led to a view -- should we not look with greater vigor beyond the shores of India so that we had the hedging of two or three economies that might offset the effects of one? So that set up a set of tasks of going to neighboring countries. We opened South Africa for automobiles.

We had a very big proposal to the Bangladesh government for a steel plant and a gas-based power plant, and a fertilizer plant -- all based on Bangladesh's gas availability.

Close to home, if Bangladesh didn't use the gas and didn't use the fertilizer, we could use the fertilizer in India.

If they couldn't absorb the steel, we could absorb the steel in India. It was a big project for any Indian company to undertake.

What year was this in?

Maybe '93-'94. It never took place. That's why you probably have never heard of it. It never took place.

It sort of went into hibernation. It was being discussed. Many meetings were held over several years, and it never materialized.

In fact, I think we withdrew finally, after a couple of years of spinning our wheels.

That, in turn, led to a concerted action of trying to go beyond the shores of India, and also a change from the Tata Group's earlier policy of only having organic growth to have inorganic growth as a means of entering some geographies.

So that was basically the genesis of looking outside India and looking even at companies that we might acquire.

One of those, the first one, was Tetley. Each company we looked at was a company that gave us a strategic position in that geography, either in an area that we were not, or in a country where we felt it was strategic to us to have a stake.

The first one was Tetley because it gave us an international brand for our tea company, which we didn't have.

The second was we bought Daewoo's truck company in Korea from the banks because it was with the banks at that time.

In the case of Daewoo, we merged the product plans of Tata Motors and Daewoo into one long-term plan, a very interesting thing because the Korean management just totally adopted--or accepted--the fact that we were one company.

Through everything they had at producing an integrated plan, product plan, and we came out with a set of vehicles, which were de-contented for India and highly contented for the Korean and the Japanese market.

Can I ask you about the Korean example? We just had a very interesting discussion in the HBS classroom in Mumbai on Samsung just this morning. A lot of the discussion was about the difficulty that the Korean managers had engaging with the rest of the world. Did you experience any such reticence on the part of Korean management?

No, actually, our experience was very good. People warned us about the difficulty of dealing with Korean unions, and we had no major trouble for almost amusing reasons. Because the Korean manpower took our company to be a Buddhist company, or India to be Buddhist.

The first day that I visited the plant after going through, standing in line, and wearing this -- virtually a uniform -- and all the trappings that go with a Korean company, I was asked to eat in the workers' cafeteria.

I was sort of appalled by that thought, because I thought I'd have to eat in silence, not speaking the language.

Although the language wasn't spoken, through collaborative interpretation on both sides, it became clear that they wanted to know whether we would fund some employees for visiting Buddhist sites in India. Once we got over that, we were all part of the same clan.

The same conversation.

The top management of Daewoo was very pro-Indian, very keen to visit these religious sites themselves.

Many of the workers did so, too. So we had labor troubles, but very organized labor troubles -- where you get a set of demands, you negotiate.

If you don't get them accepted, they wear armbands and come to work. They put out another set of requirements, and in three or four days or five days, it's all settled very amicably.

GM bought the car plant, had lots of trouble...

Because they were not Buddhist?

Perhaps so. So our dealings with Daewoo in Korea have been very, very good.

For a long period after that, there was nothing, until the management of Corus came to us and said, why don't we come together in some form? The management at Tata Steel thought we could maybe take on joint development projects together. That made no sense -- the two companies had about the same value.

One was 19 million in terms of output, one was 5 million in terms of output. We were 5 million, they were 19 million.

The valuations of the two groups were the same. So it seemed like it made sense to come together, to merge.

Everything was fine, except the Brazilians came in and upped the ante, which led to a higher purchase price. But we were virtually there.

For the first two years -- most people today consider Corus to really be a white elephant, but the first two years it was profitable, which people have forgotten.

It's the economic situation in Europe which has impacted the European steel industry, including Corus, quite substantially, which everybody has just sloughed off.

Then we were similarly approached by Ford in the UK saying that Ford in the US wanted to find a buyer for Jaguar Land Rover [JLR].

We spent a year in almost secret discussions because I didn't know what we would do with Jaguar.

Land Rover fitted in on top of our SUV business, but Jaguar, you know -- what did we know about premium cars? Ford refused to separate the two.

We found out why, because it was integrated in terms of manufacturing facilities.

It was very difficult to pull them apart, and so we ended up acquiring JLR as such.

Interesting form of acquisition because we weren't permitted to visit the plant, we weren't allowed to talk to the management.

We were advised not to go and look at the dealerships. So you had a $1.6 billion purchase, which was sight unseen. When we did go in, I was amazed.

I'm sorry, that was for secrecy reasons?

That was the way they handled it -- They had a data room and no data was withheld, but physical presence was denied until the serious buyer was decided upon.

They were looking at multiple suitors, if you will. And certainly, in our case, we were not permitted to look at what we were going to get.

Finally, when we did do it, I was amazed at the level of technology we had, the engineering skills we had.

The manufacturing systems that Ford put in place -- Ford and BMW -- who, at different times, owned the company.

So we had the benefit of lots of changes by BMW for the Range Rover brand, and by Ford for the Jaguar brand.

But we had a different set of problems. We had a workforce that couldn't understand why we were acquiring this.

There were rumors that were going around that this was a real estate proposition, we're going to take all the plants and take them to India and convert the Birmingham/Coventry plants into a real estate project, and that everybody would be out of a job.

There were rumors that we were going to have Tandoori chicken restaurants all over the Midlands.

There were rumors that we were going to infest Jaguar Land Rover with low-cost cars, like the Nano, and that this was just a vehicle to propagate our sales.

I had to hold, I think, three or four town-hall meetings with the employees, allowing them to ask me these questions, and telling them that we had no such plan -- and that let's work shoulder-to-shoulder to bring these two brands back to the glory that they had.

To their credit, the workforce has done just that. So I think that's what started the move to go overseas.

Perhaps as an offshoot of those vignettes, can you reflect on working with the Indian workers on the plant floor, the Korean workers, and the English workers? Other than small differences of language and so on, has it been similar sets of experiences in terms of motivating them, keeping them part of the Tata family, etc.?

No, in each case, our expatriate Indian manpower into those companies, you could count them on one hand.

I think, at best, there may be four or five in each case. The interaction is different.

In Korea, it's very disciplined. In JLR, initially, it was impossible to hold a meeting after 5 in the evening. Everybody had to go home.

Tetley was, in a way, an international company anyway. I was not very closely connected with Tetley, so I can't tell.

Corus was even more complicated because there was the Dutch element, there was the English element, and now there is the Indian element -- and each one was very protective of their culture, and their turf, and their seniority in the picture.

The Dutch company was very much the gold standard in steel making. People, including us, had consultation with that company when it was on its own.

It was acquired by British Steel and became Corus, and they felt they were providing the profits and were being consumed by British Steel.

Who are we, the Indians who are coming into the picture now, owning the whole lot of them? So there was internal strife in the Corus thing regarding the Dutch company being run by the British, and now also by the Indians, and the Dutch didn't have adequate visibility and prominence.

So I'd say the greatest problem has probably been with Corus in terms of integration. Less so with Jaguar once we got over the initial hump.

Also, I think success also breeds faith and confidence in each other. So JLR was fortunate to have that success, and that has done a lot for this.

Most of all, we had to change the CEO of Jaguar Land Rover from the one we inherited from Ford.

The current CEO, Dr Ralf Speth, has done a terrific job of leading this team of people, and I think a great deal of the credit has to go to him for turning the company around. He has really provided transformational leadership in the company.

You mentioned in passing rumors that Nano would do things to the JLR factories and so on. Can we talk a little bit about Nano because it was such an interesting episode in so many ways? What are your reflections now at this point in the attempt to build that particular product for the mass market?

You've spoken a lot in the past, including at Harvard, about the reasons why you went into building that. But what did you learn from the design process, the marketing, the development of the entire business system?

It was a tremendous sort of learning exercise in terms of what we did right, what we did wrong, and what external circumstances existed, which contributed to this.

As I have said many times, the idea of having a new, affordable family transport came from watching families of four or five on two-wheelers in the rain and in the night, and feeling that this was a dangerous form of transport. And we went through several evolutions of trying to make the two-wheelers safer, going to three-wheeled transport, doing something that was akin to an auto rickshaw but more carlike until we finally emerged on a small car.

The price point was, by happenstance, fixed by the Financial Times of London, I think, through a statement that they made, and I decided again we could refute that or take that as a task.

I chose the latter, and I think with the disbelief of my people, who thought that this guy is crazy. But we took this as a task, and we set about designing a car, not a half-car, not a car that was not painted or a car that looked different, but a regular car with roll-up windows, and air-conditioning (as an option).

As a people's car, in three stages of trim. Up until then, this was a terrific exercise. We achieved what we set out to achieve.

The service of those cars was supposed to be done by young unemployed technical people, whom we would train as service engineers, give them a Nano, and they would have a territory that they would serve -- almost taking service to the home, rather than car owners coming in to us.

And after making the first 100,000 cars, we were going to have small assembly plants where, again, we would have young entrepreneurs whom we would train -- and we would also train their manpower.

We would oversee their quality assurance, and they would have satellite operations. These would interact with the service people. So it was sort of maybe a bit of a dream, but the goal was giving employment beyond the conventional form of manufacturing cars.

There were many challenges to that. For example, you had to create kits that you would provide to these assemblers.

There were issues like you can't weld a painted body part, so we had different forms of adhesion.

It was a really good exercise, almost verging on the kinds of experiences you go through in space exploration of dealing with problems that are there.

As all of us know, I think, a month before we would've been online in the marketplace, Mamata Banerjee mounted her offensive against our plant.

Without going through those details, it led us to pull out of West Bengal a totally complete car plant on the verge of going into production. And we moved, as it turned out, to Gujarat.

It took us a year to reestablish the plant, to build it afresh. In that year, we lost a lot of excitement for the product.

When we announced the product in Delhi, we got, I think, within the next week or so, 300,000 orders with full cash payments, and we became a banker suddenly.

We were giving back interest to the people who wanted a car, but the car was not to come at that time.

We had, over a period of time, people starting to want their deposits back, a loss of interest, and maybe some degree of disbelief that this was just something that you launched on a platform but that it wasn't really a workable project.

Competitors had a great time spreading those kinds of stories. But then, those were somewhat beyond our control.

Where we made our greatest mistake, in my view, is, when the car did come out of Gujarat, everybody had become quite complacent with the 300,000 applications, etc that we dropped all these nonconventional plans. And we pushed the car through our regular dealerships.

They weren't really keen or interested in selling a low-priced car with low margins, and they really caused a lot of damage by trying to sell everybody up if they came into the showroom, and this is not what you want.

The other mistake we made was we allowed the car to be titled as the cheapest car in India, instead of the most affordable car, or to not talk of its price as its only attribute.

What we did was we created a stigma about the car. So people thought, 'I don't want to be seen in that, my neighbors will think I can't afford a more expensive car.'

Those two issues, I think, were the greatest mistakes we made. We initially had planned to go into the rural areas and sell the car like a motorcycle got sold, on the market day, to work the registration, insurance.

The owner could go away with the car. We never did those kinds of things because our dealers weren't interested in taking that kind of trouble. And then it was too late.

The momentum unraveled.

The momentum had gone. Today, we're looking at relaunching the car with more bells and whistles and capabilities. But the car is now ten years old, and while we're seeing more and more on the road, still the incremental number is very, very small. So we failed to really market a people's car that we had initially conceived of.

It's a very interesting episode. On the design side, I remember having a lot of discussions at HBS about the design of the car. I know Ravi Kant...

Yes, Ravi Kant was the managing director at that time.

...so he had come to some of those discussions. But is there any enduring effect on either the car company or the broader Group of this idea of pursuing the people's car, of an affordable product?

A little bit of that philosophy sparked off the water purification project in Tata Chemicals. But I think we missed the boat in terms of doing something spectacular.

For example, the Nano would've just been another car had we had a 500,000 rupee Nano.

A 100,000 rupee Nano was something that everyone said couldn't be -- a 100,000 rupee car was something many said couldn't be done.

What Tata Chemicals did was lower than what the majors had in the marketplace, but not an unbelievably low price.

So it just became a lower cost water purifier. It's selling, but it's not a huge runaway success.

Other than that, there has not been... if I were to be accurate, I'd say Tata Housing, Tata Nano Housing Project, but they just took the name.

They didn't implement it.

No, no. They just called a housing project the Nano Project. They just used the name there.

That's another interesting issue in India, which is for maybe half the population that needs products and services at a particular price point. Getting the market to work for you in support of those goals has, I think, proven to be quite difficult. And you have the isolated success. Is that a statement that you would agree with, or is that overstating it?

My own assessment is that the market is very demanding of such products.

It's a very sensitive market in the sense if you have a calamity, you can't give secondhand clothing or yesterday's food.

No one wants to be seen or categorized as getting a handout. So whatever one does, one mistake that one makes, of trying to show that we're doing it for the person who can't afford to get something else, is the wrong approach.

You can get the price there, but you have to market the product as being just as good as everything else.

The Nano should've been viewed as something that could be in a garage that has a Bentley on the one hand, and a Nano to go to the market -- not something that is known as the cheapest car.

That's some of the mistakes we made. So I think the base of the pyramid is keen to have its own place and status in the hierarchy of the consuming public, which one needs to respect more than we have been doing.

The second thing I think is we have a tendency in India to start and scale up as we go. And I think the way that this goes is you have a big splash, you come out with a certain volume as you do in the West, and you market it and you saturate the media -- or now the social media -- with advertising.

You make it the thing you have to have. I think India is quite prone to that.

Online marketing has shown that in the acceptance of the digital environment and the satisfaction of having something delivered to you at your house that you pay for in cash.

They're quite willing to make a whole transaction online. I would've been the greatest disbeliever of that three or five years ago, but it's true.

Maybe I can shift gears a little bit -- the Tata Group under your stewardship, and even prior to that, has been an enormous catalyst to upgrading the environment also within which it operates. Whether it's holding true to not participating in the corruption, as a simple example, or having very pro-worker policies, as in Jamshedpur and other places in the past. When you look forward and see some of the continuing social-economic issues in India that companies need to be cognizant of, what is the role that you see that large corporates can play in fostering a better work environment for the rank and file individual?

Yes, I think in a country like India, or in the developing world, where you have differences in living standards and facilities for your employees, as against the communities in which you operate, there has to be a sensitivity to becoming a part of that community, and not becoming an island in that community that looks down on the community as you may have in feudal times.

So a corporation, I think, has to become part of a community, has to participate in that community, do things in the community which allow dignity to the people involved. But bring them closer, and issues such as engaging the community in service or support of the corporations, as an example, creating an activity which might stitch uniforms for the employees, or make lunchboxes for the canteen, or for the cafeteria; or create skills -- carpentry skills and electrician skills, which would help self-employment.

Give education, medical help. All those kinds of things are things corporates can do, and in fact should do, in an environment like India.

You can't just have ivory towers with depressed conditions all around them and feel satisfied.

One has to say that you need to upgrade the lower elements to a level of prosperity.

I think our early days of independence where we did the opposite -- we taxed the rich so that everybody would be equal, but by coming down.

I think you have to go the other way. You have to look at what it takes to lessen the discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots.

But by bringing everybody up.

By bringing everybody up. There may be some sacrifice for the very wealthy, but not to bring them down. To bring the others up to a level where there's sustainability there.

Do you think that our corporate elites in this country -- they would all say the same things, I think. Most people would be comfortable saying things like that. But do you think that the environment is actually moving in that direction? Or is there cause for greater concern than say, ten years ago?

Well, I think they were not talking against any one or group of business houses.

It isn't that you are doing this to say you're doing it, and then cut corners in terms of what you do, or do something that you give visibility to but behind that, everything remains the same.

It has to be something that you genuinely want to do, that you can be proud of. And jumping away from that, the greatest weakness of India is poor enforcement.

So if you want to create low emissions in your plant, or that's mandated to you by the government, and if you can get around it and cheat on that, and enforcement will allow you to do that, that's not what a corporate should be doing.

So you could say the same through a whole series of issues. A corporate should not do it for the sake of saying it, but should be ready to have anybody survey or test whatever they've said in an open manner.

There should be a willingness to have an audit at any time that one chooses to do that.

You will find very few that will allow you to do that because they want to show you what they have.

So there has to be a willingness to really create a sustainability or prosperity in that area.

Some corporations do this and are very proud of what they do. There are many, I think, that say they do it but do not.

At the outset of this conversation, you spoke about your desire to maintain the level of ethics in the Group, particularly in the context of declining ethical standards in India. This is going back to the 1990s. What is your reflection on the ethical standards of the country now? Are they flat lining at a dismal level? Are they improving?

Regrettably, I don't think it's improving. I think it's getting deeply embedded in the system, unfortunately.

I've been criticized for saying that India should not become like a banana republic.

Oddly enough, I think of all the things I've said, right or wrong, this is the most correct thing I've said. Because we really need to be concerned that we do not become victims of a vindictive government or a vindictive administration at lower levels, that we work towards a common goal of making India into an economic power with equal opportunity for all people.

That's not where we are today, and I don't think there are too many people that want to change it. Or not enough people want to change it.

So a personal reflection, just watching dozens, hundreds, maybe even thousands of students, both at Harvard, of course, but also here: My reflection is that, at least amongst the better educated subsets of the younger people, many more of them seem to be willing to strike out on their own, as opposed to joining a corporation.

Not enough to move the needle, still, but significantly more than when I was starting my career or prior generations. And that gives me a lot of hope. If there was some way to take that -- for want of a better term, I would just call it at startup culture, and scale it across the country -- I would personally find that very heartening. Do you have any comment on that?

I think there's a definite change in the environment. Startups ten years ago would never have a chance to really take form, let alone scaling up. And even five years ago, a startup would be very lucky to survive the initial hardships of getting something in place.

There was no venture-capital funding available. Things were looked at in a traditional banking form, and there was never bankability of these projects.

There were no investors who were willing to take risks, so what would happen is that those entrepreneurs who were lucky enough to have an education abroad might form a very successful startup in the US or somewhere else, and possibly never come back to India.

Today, I think things are very different, mainly because of money from outside India, which is something we just look at as a wonderful thing that's happened -- that Alibaba has made big investments in India, or SoftBank has recognized some startups. But we have to realize that we are setting up Indian startups in India with foreign funds, which is fine.

I have nothing against that, but we need to ask ourselves why Indian funds are not wanting to make those investments, not willing to take those risks, not willing to support young people who have a good idea, not willing to make the effort to assess the value of the product or the system or service that is being talked of.

I think on that we need to encourage Indian venture funds to be established, giving our Indian startups a chance to grow in India. And this is, in fact, starting to happen. But you need much more of it to be truly satisfied that we have an Indian business at the base of the pyramid, or wherever it may be.

I think the important change is that we have a situation where some young people can get together, get an idea, and find the funds to establish and implement that idea, which didn't exist five years ago.

I wanted ask you a very open-ended question. If we again think about India, or for that matter, other developing countries, there are so many pressing problems that some days I wake up and I'm not sure whether to feel depressed or not. The environment -- Delhi has become now one of the most polluted cities in the world, for instance.

Water pollution is legendary, in a bad way, around the world. Our public health indicators are better than they used to be but still nothing to be proud of. We have a 100 million, maybe more, young people entering the workforce. Our government generally has not been proactive enough about providing the public goods that the textbooks tell us that governments ought to be providing.

To the extent that you have time to think about such encompassing problems, how do you think about them? Either consciously or unconsciously.

I'm sure the different companies in the Tata Group have had to deal with these sorts of issues. What approach should we be taking as a society to addressing these problems?

Well, first of all, all the issues you raised are essential issues. I would be the first one to say that anybody who considers any one of those issues as something you shouldn't be concerned about is defaulting on his responsibilities as a citizen.

Coming back to what I said a little while ago about enforcement, why are our rivers or our drinking water polluted? It's because people are putting untreated water from plants and industrial units into rivers -- sometimes toxic and, in fact, fatally so.

Why is the air being polluted? Because people are taking shortcuts on antipollution equipment or scrubbers at power plants and fertilizer plants, etc.

In any one of these areas, you find there are polluters and there are people who are going against the laws of the country, who can manage to continue to do that.

While everybody could determine what the cause is, the cause is skirted around because there's corruption behind it.

So we're back to an issue of one of the greatest things that could happen in India is to enforce the law as it should be.

Not to create new laws to take care of -- as though everybody is a defaulter. We need to enforce the law where it's necessary, and we should do it irrespective of who is involved.

The law should apply to everybody without exception -- sort of a Singapore kind of approach to enforcement.

If we don't do this, it's again an issue of creating a power base with a local politician or a local administrator who can enable you to bypass this if he wishes.

What can we do about it? The reason I am focusing on policy -- I mean on enforcement rather than policy -- is that the policy is usually in place.

If you look at the government policy network, there has been some law or some policy that covers this issue, but it's not enforced. And so, I keep coming back to the same thing that you need an enforcement agency -- for most part the police, but it could be the civil administration -- that has the responsibility for legally enforcing the law, not vindictively, but for everyone to abide by.

You can deal with these issues consciously in an environment that you may control, or around the environment you can control. But you can't do this on a national basis.

But sadly, I'm tempted to say that it's not an issue of education, because people know that polluting the river is a bad thing. There isn't any education necessary to communicate to those who do it.

My suspicion is we need to move beyond admonition, and I'm trying to think, is there anything that we could do creatively, perhaps get groups of corporates together to put pressure in a certain geography -- just thinking aloud -- to move away from the recognition that this is what's happening to something that maybe compels the government to enforce the laws, or compels the civil service to enforce the laws. Because the status quo will continue to yield even greater pollution and health problems than we have currently.

I think to a great extent the status quo is going to continue to exist so long as there are some people who can find ways of evading the law and can use influence, or power, or money to enable them to do that to their advantage. It's a double-edged sword.

It's to give them added margin where other people have cost, and similarly, in their own business it probably is the same way in which they get additional margins for that purpose. I'll give you an example, which I think typifies what you have said.

Our trusts have been funding schools in the state of Bihar. There are ten schools in the example I've been giving that we were funding, until we found out that the teachers received money, obviously, as salaries, and they received certain additional compensations for each class they taught. But they never taught the class.

The principal and they colluded, and they'd go away. They'd sign in and go away to do other jobs or whatever. The kids were very happy, never went to school.

This was appalling, and what was really appalling was the government was sending money for midday meals, which the kids never got.

The money was shared between the principal and the teachers again. We went to the police -- they didn't wish to interfere, and we pulled our money out of those schools.

This is just an example of hundreds of thousands of things that are happening in the same kind of way.

It just enumerates the kind of attitude that there is. So if we want to put an end to this, I think there has to be a total zero tolerance, nonacceptance, of this.

This can't be done by you or me. It has to be done by the government and/or its machinery of enforcement. It sounds a little draconian, but it is truly a problem.

I wonder if there's any benefit to highlighting the positive stories where somebody does do the right thing?

Yes, that's true. There is a virtue in doing that. But unfortunately, those examples are those who have done that despite the issues we've talked about, so the dark side continues to live a life of its own.

You know, by nature I'm an optimist, and one of the things that gives me a little bit of optimism, other than the entrepreneurship that I see starting to flower, is again an anecdotal observation that I'll ask for you to comment on.

Particularly in the last twenty years, as it has become possible to start new enterprises earlier than used to be the case, and some young folks have made modest or sizable sums of money fairly early on in their careers, I've been watching a number of them go into giving back in different ways. Into starting nonprofits that might be focused on education, or public health, or governance, or transparency.

Also observing some of them running for office from so-called respectable backgrounds -- whereas, when we were kids growing up in Bombay or wherever else, you joined the professions, or you went into a family business as a respectable career choice. You didn't go into politics usually.

I think that's largely a good thing to find good human capital going into political life or creating social organizations once they have reached a certain level of material comfort. Is that an observation that you would share or have any comment on?

I think you see this around quite a lot these days. I just want to correct an impression that you have.

I'm an optimist also but I'm frustrated from time to time.

I'm an optimist in the sense that there's such a tremendous potential amongst the people. Even if there is poverty, the young kid who is selling you a magazine at a red traffic light is making a living, or trying to make a living.

He's not sitting under a tree poking his arm with a needle. There perhaps is the highest degree of entrepreneurship in our country -- everybody has a desire to be doing something and making a contribution -- we need to harness that in some way.

We need to give everybody a sense that they're equal. There are people who don't have the opportunity of having a good education.

It doesn't mean that they're useless, and if you were to say, what can we do, I think we have to create more avenues of making this possible.

We need to look at vocational skills to be given. We need to upgrade people.

Once Mr Lee Kuan Yew [first prime minister of Singapore] told me that the greatest thing he did in Singapore was to make English the first language.

It has kept Singapore connected to the rest of the world.

There's a lot to be said for looking at a similar kind of thing to improve the market value of people in India in the service industry, in the tourist industry, in office environments.

I've often wondered if we had a curriculum, an optional curriculum, that taught colloquial English, which would raise the value of the person and enable him to operate in different environments, what would it do to the service availability of our people? I think it would be quite sizable. But if we did that, these people would have an urge to do something with that.

It's not like another country where they would sit back and bemoan the fact that they didn't have a job. They would go out and do something.

What's sad today is that there are so many people who cannot find work, not because the country is devoid of that opportunity, but because we are not doing enough in the country.

So I'm optimistic of what we can do. I've often felt that we have an Indian tiger that needs to be uncaged. And the only way to uncage that is to have an open environment where you have less regulation, better enforcement -- but less regulation.

That you treat everybody as equal. You don't have this -- I don't want to say caste system because it's not necessarily that -- but stratification.

Mr. Tata, on that optimistic note, let me on the behalf of both of us optimists thank you for taking the time to speak with us for this project. And thank you on behalf of this entire team since we've all been working together. We appreciate it greatly.

Thank you. It's been a very enjoyable experience interacting with you. And I hope I was able to add a little value to what you're trying to do.

Photographs curated by Manisha Kotian/Rediff.com

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025