A big part of what India is missing here is talent or expertise in precision engineering and manufacturing.

Tata Motors recently cut the sales forecast of its luxury car brand, JLR, due to chip shortages, scaling down its production numbers from the earlier 120,000 units to 60,000-65,000 units by September, and leading to an almost 10 per cent fall in the company’s stock.

In May this year, Bosch India, too, had stated that chip shortfalls would impact its production, as supply chains were getting disrupted.

It saw the scarcity continuing until 2022.

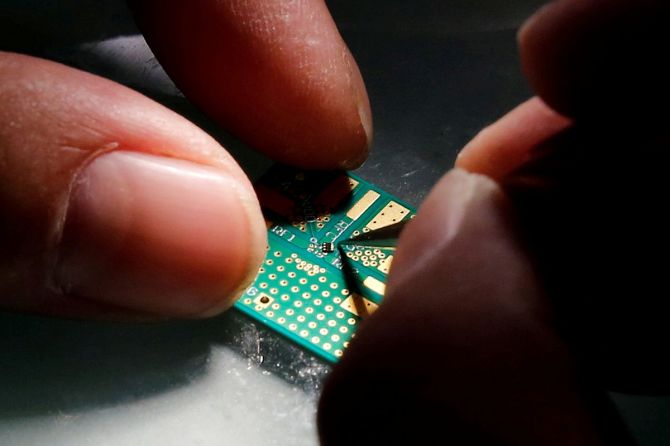

The world is facing a shortage of chips, and India is no exception.

The question is, when will India have its own semiconductor plant?

And if India is far away from having a full-fledged semiconductor fab, what other options does it have?

Rajeev Khushu, chairman of the India Electronics and Semiconductor Association (IESA), believes that the country should take the first step towards manufacturing semiconductors by setting up ATMPs (assembly, testing, marking and packaging) and then get into specialty fabs.

“ATMPs as the first step would be ideal for India. This gives some presence in the semiconductor ecosystem and they require much less investments and generate more employment,” says Khushu.

Many ATMPs are situated in south-east Asia.

Taiwan and China are the leading players but Vietnam, Singapore, and Thailand also have a considerable number of them.

The second option is to set up “specialised fabs”.

Instead of focusing on the most advanced technology, these fabs use more mature and older technology.

Technology advancement in the semiconductor industry is defined by the nanometer number.

Leading-edge technology today would be 10 nanometer nodes (nm), 7 nm, and so on.

“But there are a lot of devices that can be fabricated with older technology like 90 nm, 130 nm, 65 nm. These are specialised fabs, and have big applications in industrial, power and automotive verticals.

"Most of the current shortages of chips that you hear of nowadays is of chips fabricated on older technology,” says Gaurav Gupta, vice president, semiconductor & electronics, Gartner.

The other advantage of specialised fabs is the cost.

A full-fledged fab would require an investment of about $15-20 billion, whereas specialised fabs would need around $3 billion.

Since these fabs are based on older technology, the technology upgrade cycle is also set to a lower pace, which suits a country like India.

Industry experts feel that the government's focus should be to take one step at a time.

So far the government has received 20 expressions of interest (EoIs). Amitabh Kant, chief executive officer (CEO), NITI Aayog, said at a recent webinar that a lot of work is going on in the direction of getting a semiconductor ecosystem into the country.

“This is our top priority. We are working on it, and we are in touch with TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company),” he said.

Building a semiconductor ecosystem needs big investments and also the infrastructure to support it.

For instance, the plants need continuous supply of electricity and water.

According to a Harvard Business School report, a single manufacturing plant can use anything between two and nine gallons of water per day.

“I think a big part of what India is missing here is also engineering talent or expertise in precision engineering and manufacturing, which has been the case across different manufacturing industries.

"This requires a fundamental shift, as the focus of the education system is more theoretical,” adds Gupta of Gartner.

He points out that that there has been progress on software, but hardware has always lagged behind.

“Even smaller south-east Asian countries are much ahead in terms of high-end manufacturing.

"That ecosystem is a critical enabler of success with chip fabrication.”

There is a section of people who believe that India should prioritise investment in “fabless” design firms that generate chip demand, control intellectual property rights and direct product sourcing.

“Once such an ecosystem is built, it can be followed up with a semiconductor fab.

"Private companies may not be able to make such high investments without a clear return on investment, and a strong fabless ecosystem gives them that return,” says Parag Naik, co-founder and CEO of Saankya Labs.

He thinks that the recently announced schemes that the government is offering may not be sufficient for this purpose.

He suggests that instead, if the government can incentivise R&D, “we can have many homegrown companies doing chip designing and this will invigorate the ecosystem.”