Though active funds charge 10-50 times the fee of index funds, most do not give remarkable returns, points out Avinash Luthria.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The active mutual fund (MF) industry keeps repeating the statement that 'the average Indian active MF beats the index and delivers alpha'.

And they use various deceptive arguments to support this statement.

These, however, are not borne out by data.

The belief in the fairy tale of alpha is dangerous because it will tempt investors to save less for retirement; invest too much in equities believing that an active MF will partially insulate them against a significant stock market crash; be willing to pay a very high fee if an MF can make an exciting case about generating alpha.

Let us examine some of the flaws in the arguments put forward by proponents of active investing.

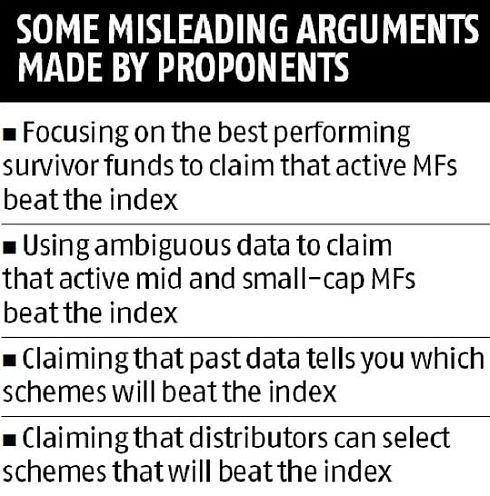

Focusing on best-performing survivor funds

Active MFs keep repeating the statement that 'the average Indian active MF beats the index'.

Active MFs' fees are 10-50 times the fees of the most actively traded Nifty50 ETF.

Hence, the onus of proof is on active MFs to prove that their expensive products provide value for money and beat the index.

The only robust analysis of Indian active MF performance is the Standard & Poor's (S&P) Indices Versus Active Funds (SPIVA) India report. The SPIVA India report shows that the average Indian active MF does not beat the index.

This report has been saying so since the first one appeared in April 2010 for the period 2005-09.

And it continues to say so in the latest report for the period 2009-18.

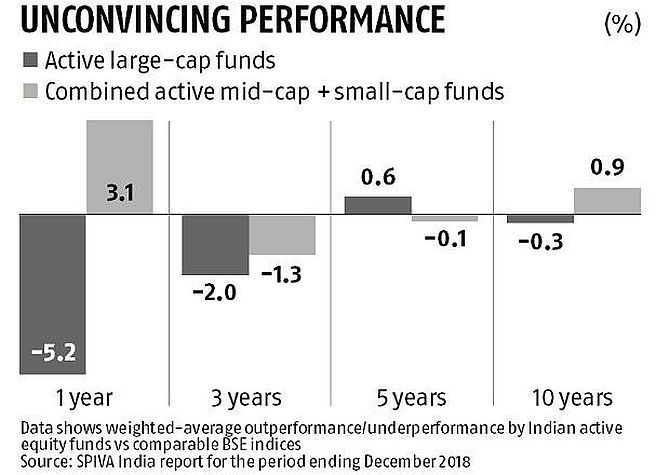

The most relevant metric is the weighed-average returns, so we shall focus on that in this article.

The cleanest data is for large-cap funds for the past 10 years, and there active MFs underperformed the large-cap index by 0.3 per cent per annum (see table).

S&P's additional research 'The opportunity cost of active management [in India] shows that the worst-performing schemes get merged into the better-performing ones.

This ensures that the data for the worst-performing schemes disappear from MF databases.

All the other analyses of Indian MF performance do not correct for this survivorship bias.

Using ambiguous data

Proponents of active MFs then argue that 'large-cap active MFs do not beat the index but mid-cap and small-cap active MFs do so, hence invest in them'.

The higher fee charged by mid-cap and small-cap funds should make one naturally suspicious about this argument.

Moreover, it would be very risky to put a disproportionate amount of one's net worth in mid-cap and small-cap funds, which are more risky than large-cap funds.

But let's focus on the data.

The BSE mid-small cap index returned 18.4 per cent per annum over the 10 years ending 2018.

The combined category of mid-cap and small-cap active MFs outperformed it by 0.9 per cent per annum.

There are several signs that this 0.9 per cent is just noise in the data.

First, over those 10 years, the average mid-small cap active MF outperformed the BSE mid-small cap index but underperformed the very similar NSE mid-small cap index.

Second, these active MFs underperformed even the same BSE mid-small cap index by 0.1 per cent per annum over the five years ending 2018, and by 1.3 per cent per annum over the three years ending 2018.

Third, because of the small sample size, S&P had to combine the mid-cap and small-cap categories.

So, the data for this combined category is noisier and more ambiguous than the data for the large-cap category.

Fifteen years of data would have helped, but no one has high quality data for the Indian market for 15 years.

Asking you to pick the right schemes

Active MF supporters then say that 'even if the average active MF cannot beat the index, our CIO (chief investment officer) is a genius and hence more than half of our large number of schemes will beat the index. So, pick us'.

The S&P's 'The Opportunity Cost of Active Management [in India]' research also shows that knowing which schemes outperformed during the previous five years will not help you select schemes that will outperform during the coming five years.

Since luck or randomness has a huge impact, it is difficult to determine whether past outperformance was due to luck or skill.

So, it is very difficult to figure out which of the hundreds of schemes will outperform the index over the next 5-10 years.

Active MF proponents' final line of defence is that 'a distributor can tell you that our CIO is a rare genius and also figure out which of our schemes are likely to beat the index'.

The distributor would have to be a genius indeed to be able to figure all this.

So, this just changes the problem to finding a distributor who is a genius.

Bear in mind that the annual commission of the distributor will make it even more difficult for the investor to outperform the index.

Due to lack of space, I have omitted many of the other arguments in favour of active MFs that are even more spurious.

Nobel prize winner William Sharpe proved mathematically that the average active investor is, net of costs, guaranteed to underperform the index.

Further, promoters of companies have the most amount of information, so they are likely to be the above-average active investors.

Hence, it is difficult for the average MF to be an above-average active investor.

This is the rationale for index funds -- the greatest financial innovation of the last century.

Nine-and-a-half years since the publication of the first SPIVA India report ought to have been long enough for Indian individual investors to get over the delusion that they are above average investors and exit the cult of alpha.

Avinash Luthria is a Sebi-registered investment advisor and founder of Fiduciaries.in.