Don't expect the synthetic stones to surpass natural ones anytime soon because the world's biggest miners of diamonds aren't looking to get into man-made diamonds.

The focus on man-made diamonds in India has grown, thanks to dubious practices by absconding jewellers, jailed diamantaires and missing tycoons that include usual suspects Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi, but the supply of synthetic stones has been in legitimate use since the 1950s and growing steadily.

According to industry reports, the worldwide production of synthetic stones grew to almost 7 million carats last year, while the production of mined stones slid to around 111 million carats -- down from a peak of more than 150 million carats mined in 2017.

But don't expect the stones to surpass natural ones anytime soon despite the Gemological Institute of America grading them as natural stones.

That's because the world's biggest miners of diamonds aren't looking to get into man-made diamonds, the scope for abuse and fraud persists with such stones, and, finally, because they have little or no resale value.

Sanjay Kothari, long-time jeweller and former chairman of Gems Council, said that for now, lab-made stones have fallen into the category of a separate business that will grow for sure.

"People are looking for other options and it is cheaper to a great extent, maybe 50 per cent or more, but there is no resale value and that is a worrisome factor," he said.

Lab-made diamonds were originally developed for use in telecoms, laser optics and industrial markets, but started to become an option in the jewellery business in recent years with the clamour growing around environment, social and governance norms that take aim at all commercial practices that damage natural habitats, reduce sustainability, and create inequalities in societies.

To an extent, the growth of lab-made diamonds is a positive in that it could potentially assist and support the diamond polishing and cutting industry that is in Surat, Gujarat, where the majority of stones in the world are processed. But their acceptance in the mainstream jewellery world has its own share of stumbling blocks.

For one, within the trade, the mode of buying man-made diamonds involves upfront cash purchases.

"Man-made diamonds are usually sold in cash and the natural stones against credit because the synthetic stones are made, like a tailored suit according to demand," said one jeweller who declined to be named. "That automatically reduces their marketability."

There are other advantages to natural stones. Jim Vimadalal, director in the Indian representative office of Alrosa, the world's largest diamond miner in carat terms, said, "In the history of natural diamond jewellery, contenders for our unique niche crop up on a regular basis: Moissanite, cubic zirconia (phianite), Swarovski crystals and now lab-grown diamonds, or LGD.:

"They are all very similar in appearance but what makes natural diamonds special is not their shine, nor their hardness or chemical composition -- it's mainly the fact that they are unique. It's similar to a work of art: No matter how good they are, copies and imitations are still just copies," added Vimadalal.

Experts estimate that people buy several billion pieces of jewellery every year worth $300-$350 billion globally.

"The average price is $100 per item. Diamond jewellery accounts for only 3-4 per cent of this sum," said Vimadalal.

"On the other hand, engagement rings with natural diamonds cost about $2,000. It is 20 times more expensive than the average item in the wider market, such as items containing Swarovski crystals, cubic zirconia," he added.

The problem, of course, is for the non-expert to judge authenticity. Jailed diamond mogul Nirav Modi and absconding jeweller Mehul Choksi have both been accused of using synthetic stones in their jewellery and products in a bid to inflate values.

Vijay Jain, formerly CEO of the Indo-Belgian Rosy Blue-controlled platinum company Orra, said that synthetic diamonds can be misused in the same way that gold ornaments were subjected to lower karat than promised in the past.

<p"No one will make a diamond necklace that consists entirely of synthetic stones but if it's a 50-carat necklace and there are a lot of smaller stones, there is a risk of the smaller pieces being synthetic."

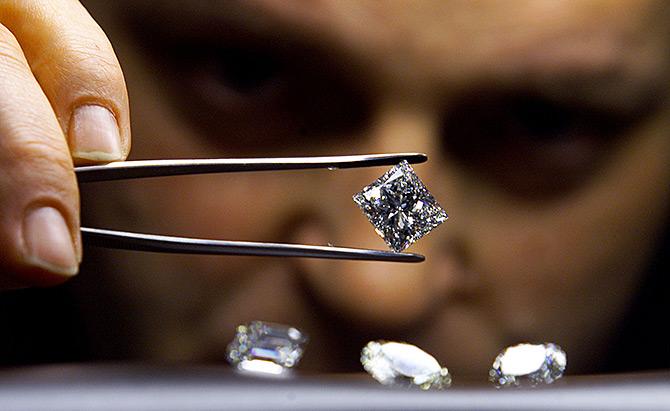

Though it is true that machines today can easily decipher natural and man-made stones, who is going to go and check every single small diamond in a complicated necklace? Experts say that a man-made stone can be detected.

"Lab-grown diamonds display the same chemical and optical properties as natural diamonds, which makes them very hard to differentiate with the naked eye," Vimadalal said.

However, there is specialised equipment, such as the Alrosa Diamond Inspector, which clearly distinguishes natural diamonds from LGDs, even in an item of jewellery, Vimadalal added.

Another way of differentiating them is tracing, a service that credibly tracks a natural diamond all the way from mine to retail.

Alrosa recently introduced a new diamond-tracing technology using non-invasive laser markings to distinguish its diamonds from others and provide detailed information about their origins.

Vimadalal does not see man-made diamonds surpassing natural diamonds in terms of demand, and it's clear that consumers in China and India (the industry's fastest-growing markets) do not view lab-made diamonds as a substitute.

While technology can depreciate the value of diamonds, synthetic stones are largely an accessory and not a core market for jewellery.

So the key question is: can it become a mainstream diamond market? The answer is unclear, given that the market depends on younger customers -- especially millennials -- with different tastes. But at least for now, real diamonds are forever.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025