'The question is, how soon we can expect to re-attain the pre-lockdown levels of output and income.'

On March 23, 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi announced a lockdown in the country due to the coronavirus pandemic. Initially meant for a period of three weeks, it has lasted months, and brought economic activity to a standstill.

In the April-June quarter, GDP shrank by 23.9% -- the worst ever in India's history.

The slide continued in the next quarter.

As the government is in denial mode, the finance ministry always spoke of green shoots appearing in the economy.

The Reserve Bank of India's first ever published 'nowcast' admits that India has entered a technical recession in the first half of 2020-3021 for the first time in the history of independent India.

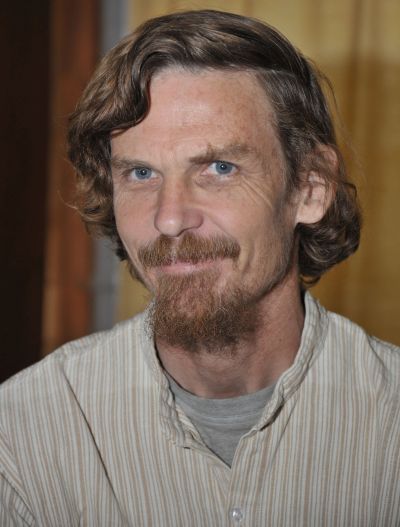

In an interview to Shobha Warrier/Rediff.com, Dr Jean Dreze, the well known Indian economist, analyses the state of the economy in the wake of the lockdown.

"I would argue for much greater focus on measures that serve the dual purpose of economic stimulus and social support instead of showering public money in all directions in the name of a fiscal stimulus, Dr Dreze says in the first of a two-part interview.

Finally, it has been announced by the RBI that India is in recession.

Even before the pandemic struck, the economy was slowing down and there was no demand in the market.

Some economists say it all started with demonetisation, followed by the faulty implementation of GST while others attribute it to the NPA crisis.

Do you think the problems in the economy are self-inflicted?

Demonetisation was certainly a monumental self-goal. It's hard to find any serious economist who thinks it was a good idea.

Unfortunately, support for demonetisation has become the most essential qualification of an economic advisor in the Modi government. So, the government is rather short of competent advisors, and that's another self-goal.

Even the NPA crisis is substantially self-inflicted. The government keeps kicking the can down the road, because it does not have the courage to stand up to the vested interests behind the crisis.

So, I would agree that some of our economic problems are self-inflicted, without necessarily blaming the government for every setback.

The COVID-19 crisis was not the government's doing, even if the government's response made it worse, at times, than it should have been.

The earlier IMF projection for this year is a contraction of 10.3%, but now it says India will register a growth of 8.8% in 2021. Is this a realistic growth projection?

Growth projections have to be taken with a pinch of salt at the best of times, and all the more so at a time when there are so many uncertainties in the national and international economy.

The basis of the 8.8% growth projection is not explained in the IMF's World Economic Outlook report. Read together with the estimated 10.3% contraction this year, it means that the Indian economy is expected to rebound next year, but not quite to the extent of re-attaining the 2019-2020 GDP level.

This seems like a plausible projection, but it is speculative at best, like most growth projections.

Despite the 23.9% contraction in the last quarter and the official declaration of a recession, the finance minister has been talking about green shoots appearing and a recovery happening. Do you see green shoots in the economy?

The expression 'green shoots' has a nice ring, but if it means that things are not as bad as they were a few months ago, it does not say much.

Naturally, after months of strict national lockdown during the first quarter, the economy is bound to revive to some extent.

The question is, how soon we can expect to re-attain the pre-lockdown levels of output and income, not just in terms of macroeconomic aggregates but also for the vast majority of the population employed in the informal sector.

And the truth is that we have no idea, because the informal sector is more or less off the statistical radar at this time. Spotting some green shoots in specific areas of the formal sector does not take us very far.

The finance minister cites the manufacturing purchasing managers index (PMI) for October rising to 58.9, the highest reading in a decade, and the GST collection Rs.1 trillion for the month of October and auto sales are up by 19%. Do you see this as economic recovery, or just a festive demand?

The PMI is just an informal indicator of business sentiment in the corporate sector. PMI data for the last few months suggest that India went through a more severe and prolonged contraction than most other countries for which such data are available.

The PMI is just an informal indicator of business sentiment in the corporate sector. PMI data for the last few months suggest that India went through a more severe and prolonged contraction than most other countries for which such data are available.

A high index for October simply means that October feels better than the previous month, which is what you would expect when the country finally emerges from the contraction.

As for the GST collections, if they are so good, then how about giving the states their due share?

Instead of playing up the green shoots, I wish the finance ministry would initiate some rapid surveys of the informal sector. Some useful surveys were conducted by independent research organisations during the lockdown, we need more information of this sort on a regular basis. Unfortunately, the government seems to prefer not to know.

The finance minister announced three stimulus packages, but they have not been able to create any stimulus in the economy. Some say they will help only tomorrow and not today. Do you think so?

Some measures did help today, such as the higher budget allocation for the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, expanded food rations under the public distribution system, and cash transfers to women's Jan Dhan Yojana accounts.

They helped not only to revive the economy, but also to support poor people in their hour of need.

These supportive measures, however, add up to less than one per cent of India's GDP.

The rest of the so-called stimulus packages is an odd assortment of bailout measures, credit guarantees, concessions to privileged groups and window-dressing.

Some of these measures may help, but many of them have very uncertain benefits. For instance, credit guarantees are just as likely to help zombie firms to survive and troubled banks to improve their balance sheets as to enable viable firms to tide over the crisis.

Similarly, it is hard to understand how a Rs 65,000 crore handout for fertiliser subsidies, or concessions to public sector employees, are supposed to be priority interventions at this time.

I would argue for much greater focus on measures that serve the dual purpose of economic stimulus and social support, instead of showering public money in all directions in the name of a fiscal stimulus.

Though the Covid mortality rate is quite low in India, economically it is the worst hit by a contraction of 10.3% globally. Is it because the sudden lockdown had a very serious impact on the economy?

India is not actually the worst hit, if you go by the recent IMF estimates, but it is certainly one of the worst hit.

One possible reason is the severity and duration of the national lockdown. Very few countries had a national lockdown rated 100 in terms of stringency by Oxford University's COVID-19 Government Response Tracker for a full month, as India did.

The Indian economy also had a relatively low ability to fall back on 'work from home' to avoid an economic crash.

The high dependence on labour migration, thrown out of gear by the paralysis of public transport, was another vulnerability.

Further, income support measures in India were quite modest, especially in comparison with affluent countries

Last but not least, about 90 per cent of the workforce in India is in the informal sector, where people can be thrown out of work without any formalities.

For all these reasons, it is not so surprising that the Indian economy was among the worst hit.

© 2025

© 2025