'I am sceptical of the Indian economy returning to a sustained high-growth trajectory any time soon.'

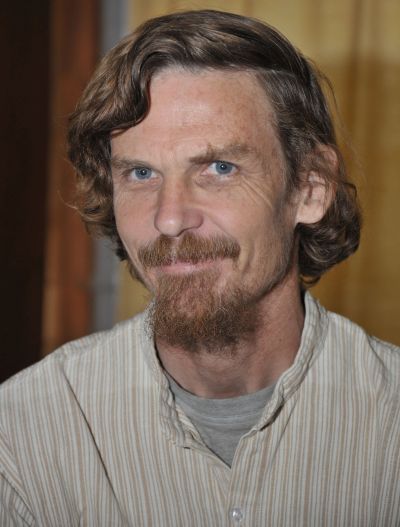

"Most people do not realise how unusual it is for an economy to grow at around 7 per cent per year for as long as 12 years, as the Indian economy did before demonetisation," Jean Dreze, the well-known economist, tells Shobha Warrier/Rediff.com in the concluding segment of an enlightening interview.

A country with 100 million migrant workers and majority of them returning to their villages, what kind of burden will this place on rural India?

It so happens that many migrant workers returned to their villages around the time when they tend to return anyway, to join the kharif agricultural operations as farmers, sharecroppers or agricultural labourers.

The difference is that they were forced to return in abominable circumstances, and with little savings.

Some of them are reluctant to migrate again for now, but many of them are likely to resume migration after the festival season, if they have not done so already, because they have no choice.

Others are looking for fallback occupations around their place of residence, for instance by setting up a makeshift stall to sell omelettes or chowmien.

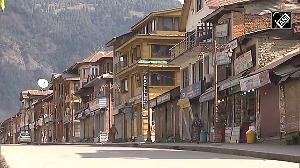

The recent proliferation of street vendors is quite visible in many small towns and even in rural areas. More street vendors, however, does not necessarily mean more output and income. Quite often it means that the same income is divided between more vendors.

So, what seems to be emerging is a situation of extreme underemployment, where huge numbers of people are eking out a living in occupations and activities that are way below their capabilities and earn them meagre wages.

The waste of human capabilities, a chronic feature of India's economy, is being magnified to tragic proportions.

When do you see an economic recovery happening in India?

As long as the coronavirus does not flare up again, I think that there is a good chance of substantial recovery in the next financial year.

But I am sceptical of the Indian economy returning to a sustained high-growth trajectory any time soon.

Most people do not realise how unusual it is for an economy to grow at around 7 per cent per year for as long as 12 years, as the Indian economy did before demonetisation.

The reason why spells of fast growth rarely last long is that they require a fragile combination of favourable circumstances, such as good trade prospects, sound macroeconomic policy, high expectations and so on.

Now that this fragile equilibrium has been disturbed, it is not going to be easy to restore it, though the economy may grow fast in specific years.

It is possible that the Indian economy will grow at 8.8% next year, as predicted today by the IMF, but it is one thing achieve high short-term growth in the rebound of a crisis and quite another to cruise at high speed for a length of time.

The head of the World Food Program warns world leaders that 2021 is going to be worse than 2020, and we are going to have 'famines of biblical proportions' Do you think the entire world irrespective of whether they are 'developed or under developed or developing' will suffer if it happens?

That biblical prophecy actually goes back to the month of April, and the predicted famines have not materialised, at least for now.

The fact is that famines are easy to prevent, and when they do occur, they typically involve a monumental failure of public action, related for instance to the perverse effects of an armed conflict.

In India, at any rate, there is absolutely no reason why a famine should be allowed to occur.

Not only does the country have ample food stocks and well-tested tools of famine prevention, the political system also makes famine too much of an embarrassment for any government to let it to happen.

Having said this, we could easily see rising levels of hunger and undernutrition, without the sort of mortality spike typical of a famine.

Indeed, that has already happened, during the national lockdown, and it could happen again, not just in India but even in rich countries like the United States.

Chronic undernutrition in India is very high at the best of times, we have every reason to be concerned about a possible worsening of the nutrition situation.

India, a country that produces surplus food, is placed at the 97th position out of 107 countries in the Global Hunger Index behind Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

We have the National Food Security Act 2013 to ensure food security to all. Still, people are hungry and 14% the population is undernourished.

Who is at fault for this situation?

Is the public distribution system insufficient or inefficient?

The so-called Global Hunger Index does not measure hunger, but an odd mixture of calorie availability, child nutrition and child mortality.

The PDS on its own cannot much difference to this sort of composite indicator. What it can do is to protect people from hunger in the literal sense of the term, and also give them a modicum of economic security.

In that respect, I think that India's PDS is playing a useful role, even if it is still far from efficient. The PDS certainly protected millions of people from hunger during the lockdown and the economic crisis that followed.

The fact remains that about 500 million people have no PDS entitlements under the National Food Security Act, with only some of them covered under state-specific food schemes.

The fact remains that about 500 million people have no PDS entitlements under the National Food Security Act, with only some of them covered under state-specific food schemes.

Not all of them are exposed to food insecurity, but even if just one out of five are, that would add up to 100 million people.

It is a mystery why the central government is not releasing more of its gigantic excess foodgrain stocks, in this crisis situation, to expand the food safety net.

Coming back to nutrition statistics, there is plenty of evidence that undernutrition levels in India are among the highest in the world.

There has been much discussion of the so-called South Asian enigma, namely the fact that nutrition indicators in South Asia are worse than those of many countries with comparable levels of poverty.

Today, there is also an Indian enigma, in so far as India's nutrition indicators are the worst within South Asia, particularly in terms of low weight among children, and among adult women too.

I suspect that a major clue to this enigma lies in India's extreme levels of inequality, including caste and gender inequality.

Just to pursue the latter, the subjugation of women plays no small role in the persistence of chronic undernutrition in India.

When women are deprived of education, voice, earnings, property, power, and freedom, their ability to take good care of children's nutrition and their own wellbeing is severely reduced.

We observed this at close range last year, in a survey of pregnant and nursing women. In states like Uttar Pradesh, where gender inequality is more extreme than almost anywhere else in the world, the special needs of pregnancy were grossly neglected, with dire consequences for both mother and child.

Many women, for instance, had no idea whether they had gained weight during pregnancy.

In places like Himachal Pradesh, where women are relatively independent, well-educated and self-confident, the situation was much better.

It is not surprising that regional patterns of child undernutrition in India tend to match those of gender inequality.

Caste-based inequality and oppression also help to explain the Indian enigma, since India is the cradle and stronghold of the caste system.

This is only one part of the story, but we would do well to pay more attention to it.

© 2025

© 2025