With so much bad news, everybody is hunkering down in readiness for Mr Modi’s next radical Big Idea, says Kanika Datta.

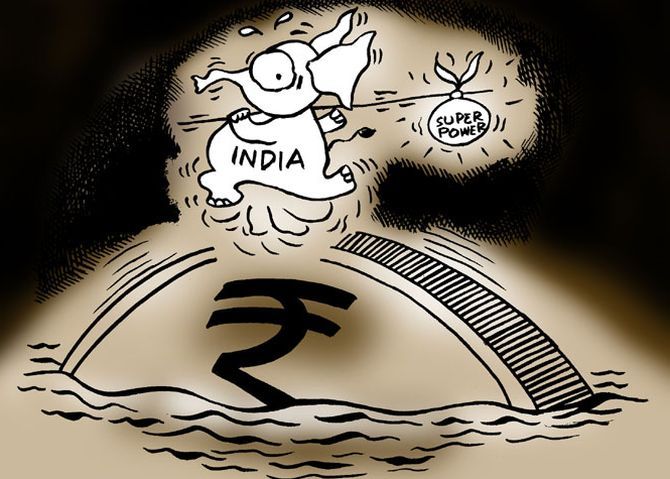

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com.

There is nothing like a sustained economic slowdown to embolden the critics of this regime and its Parivar adjuncts.

For this, due acknowledgement must go to respected party elder and former finance minister Yashwant Sinha.

His article on the state of the economy in The Indian Express in late September explained, in the bluntest possible terms, the truth about the emperor’s clothes or lack thereof.

Mr Sinha’s plain-speak echoed what apolitical economic commentators had been suggesting for months.

Indeed, the fortnight before, even the maverick saffron knight Subramanian Swamy had been no less candid about the government’s economic management.

“The economy is in a tailspin. Yes, it can crash,” he said in a CNN-News18 interview.

Mr Sinha’s unexpected radicalism concentrated minds because he claimed to speak for the party rank and file who dared not voice their misgivings, and its placement in a mainstream daily with a reputation for non-conformism clearly irked Raisina Hill enough to provoke a defensive and curmudgeonly response.

Ever so slightly, the dam of restraint is being breached under the flood of inconvenient facts: Five consecutive quarters of slowing growth, lay-offs, shrinking demand.

The mainstream media, cowed by the fell hand of an irate PMO, began to offer cautiously critical assessments.

The chatterati in urban drawing rooms and the febrile universe of social media do not speak for all India, it is true, but the noticeably changing tenor of the conversation in these spheres can be considered leading indicators of deflated optimism.

Till last year, India was the world’s fastest growing economy, as the hopefuls unfailingly reminded the doubters.

The business press anxiously waited for signs of a turnaround. Prominent business supporters stridently ascribed the expected bonanza to dynamic prime ministerial action.

Now, that same community is talking gloomily -- and, more to the point, openly -- of opaque horizons and the absence of demand.

Till late last year, the Modi government was invincible and sagacious, if you believed the popular narrative.

Now the worried questions are all about what the government can do to stoke growth and create jobs (short answer: Very little).

All the doubts that lurked below the surface are on the table-top now.

Till January, no one doubted that the Bharatiya Janata Party’s chances of a massive comeback in the 2019 elections.

Now, that forgone conclusion is an open question -- though the parlous state of the Opposition suggests that it shouldn’t be.

Can Rahul Gandhi and the Congress party rise to the opportunity (Berkeley eloquence notwithstanding, probably not)?

The demons of demonetisation, hailed as an act of supreme courage by a prime minister determined to fight the scourge of black money -- or so the official narrative went before the story changed to promoting digital inclusion -- have come to roost.

An impressive electoral victory in Uttar Pradesh seemed to vindicate the prime minister. That the impact of the world’s largest demonetisation exercise did not show up in the immediately following quarter, suggesting that the gamble had paid off.

Now we know otherwise but the economy did not get a chance to recover from that shock therapy before the government decided to administer another.

The Goods and Services Tax, with all its complexities and glitches, was introduced at warp speed without the benefit of extended testing that such a system would warrant.

The compelling election-style slogan, “One Nation, One Tax,” and a dramatic midnight launch proved to be India’s tryst with slowdown.

Unlike earlier criticisms, the aggressive defenders of the saffron faith will find it hard to defend this manufactured slowdown -- that too, just as comparable economies are growing.

And few governments have attracted such widespread serial protest movements almost from the get-go.

Each time, though, the armies of bhakts in saffron armour had an intimidating riposte.

Those who returned state awards in protest against a perceived climate of intolerance could be excoriated for being anti-national.

Those who rejected the burning of churches, the lynching of Muslims and outright communal overtones of banning cow slaughter could be dismissed as “pseudo secularists” and invited (for some mysterious reason) to go to Pakistan. Assassination was an option, too.

As the quality of the public discourse sinks lower and lower, the convergence between the ruling dispensation’s religio-social agenda and economic performance is also becoming clear.

Banning cow slaughter, restricting cattle trading and indiscriminately closing slaughter houses may fulfil a saffron agenda but they have impacted India’s most successful businesses -- dairy-farming, leather processing and beef exports -- with all the concomitant consequences of income and job losses, compounding the hardships imposed by demonetisation and the hurried GST deadline.

With so much bad news, everybody is hunkering down in readiness for Mr Modi’s next radical Big Idea.

No one of any political hue wishes India this fate. Time for a little secular pragmatism, perhaps?