'Concerns about India's future are hampering private investment.'

'If the private sector sees strategy, teams and execution on these issues, this will inspire confidence in India.'

'This should be our main strategy for 2017,' says Ajay Shah.

Difficult business cycle conditions have prevailed from 2012 onwards.

Investment is weak, and there is stress in one-third of the corporate balance sheet and three-fourths of the banking balance sheet.

The demonetisation shock will weigh on 2017-2018. How can policymakers respond to this situation?

Fiscal policy is largely ineffective. While there is a case for rate cuts, monetary policy will not make much of a difference.

This is a time for economic reforms.

From 2012 onwards, India has experienced a business cycle downturn.

Recessions in India feature a mix of low investment and low corporate profitability.

An additional feature that has adversely affected the economy this time is a balance sheet crisis.

Roughly one-third of the corporate balance sheet was under stress in 2016: These firms were not making enough operating profit to pay interest.

Roughly three-quarters of the banking balance sheet was under stress in the second big banking crisis in 20 years.

This was the sombre environment of late 2016.

Demonetisation has induced three shocks.

There is a demand shock, as people buy fewer things.

There is an uncertainty shock, and enhanced policy risk, which adversely impacts upon investment and adds to the demand shock.

There is a productivity shock as contracts and firms get disrupted, and banks shun banking in favour of counting notes.

The story does not end in March or April, when all ATMs are brimming with cash.

Some firms, which were teetering on November 7, will go bust.

Some firms and individuals will have piled on too much debt. They will have top priority of paring down debt, which will hamper their purchases.

The disruption of some contracts will take time to heal as firms and individuals find new ways of working to be able to produce effectively.

The demonetisation shock runs for five months (November 2016 to March 2017).

After that, 2017-2018 will be a time for healing from these difficulties.

There are scenarios where it gets worse, through feedback loops between firm profitability, balance sheet stress, the banking crisis, and investment.

Vigorous policy efforts are required in order to avoid those scenarios.

How can policy makers respond to this situation?

Let's start at fiscal policy.

Indian public finance hangs by a thread: Debt stability requires high GDP growth.

When GDP growth falters, there is fiscal stress.

Low GDP growth will hamper tax revenues.

The dividend distribution tax and the corporate income tax add up to 35% of tax revenues.

This makes tax revenues procyclical; in a downturn, tax revenues are particularly weak.

It is likely that corporate profits in 2016-2017 will be weak owing to the demonetisation shock in five important months.

In 2015 and 2016, the government rejected the proposal to expand the deficit.

This same discussion will doubtless take place again. The case for fiscal prudence is even stronger, as we now have greater fiscal fragility.

What about monetary policy?

Normally, a large demand shock yields softness in inflation, and some of this is visible today.

If the agricultural inputs for farmers have been adversely affected by demonetisation, this will unfortunately yield food inflation.

Let's be optimistic and hope that this does not happen.

In this case, there is a fair chance of headline inflation (year-on-year CPI inflation) going below the target of 4%.

In this case, the Monetary Policy Committee should vote in favour of lower rates.

The trouble is that such reasoning is for normal times. At present, the monetary system has been disrupted.

It will take time for banks to get out of counting notes, for cash in circulation to be restored to normal values, for money market conditions to return to normal.

While the monetary system is disrupted, cutting rates will have limited impact.

Further, changes in monetary policy have an impact over a long time horizon: Between one to two years out.

A 200-basis point rate cut today will yield little impact in calendar year 2017.

The standard tools of macro policy are not available. What is to be done?

The key thing to focus on is private investment.

Private corporate investment holds the key to business cycle conditions in India.

In the past, we have seen this fluctuate from 16% of GDP to 7% of GDP -- a move of 9 percentage points of GDP.

These are very large movements. Each 1 percentage point of GDP is Rs 1.4 lakh crore.

A change in private corporate investment of a few percentage points dwarfs anything that can be done by the government directly through its programmes.

At present, private persons are gloomy and holding back from investing.

The CMIE tracking of private projects that are 'under implementation' shows a decline from Rs 52 lakh crore in 2012 to Rs 43 lakh crore today.

The decline is worse once we adjust for inflation, and when we divide by GDP.

This calls for an emphasis on policy and not programmes.

Direct government action, through programmes, can do small things.

Indirect government action, through policy, can change the incentives of private persons and thus matter disproportionately.

What does this entail?

The laundry list of areas for reforms is well understood.

Judicial reforms, the criminal justice system, tax policy (GST and DTC), tax administration, financial reforms (IFC), labour law, building the NPS, NPS enablement of EPFO, policy and administration in the Companies Act, bankruptcy reforms, institutional arrangements in mining and infrastructure, road safety and regulation of pollution are high on this agenda.

The government has begun on two of these -- GST and bankruptcy reforms.

In these areas, there are weaknesses of follow through.

There is a need for strong technical teams that can be a part of this work on a sustained basis, which can hang on to essential ideas and see them through to execution.

Concerns about India's future are hampering private investment.

If the private sector sees strategy, teams and execution on these issues, this will inspire confidence in India.

This should be our main strategy for 2017.

Ajay Shah is a professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi.

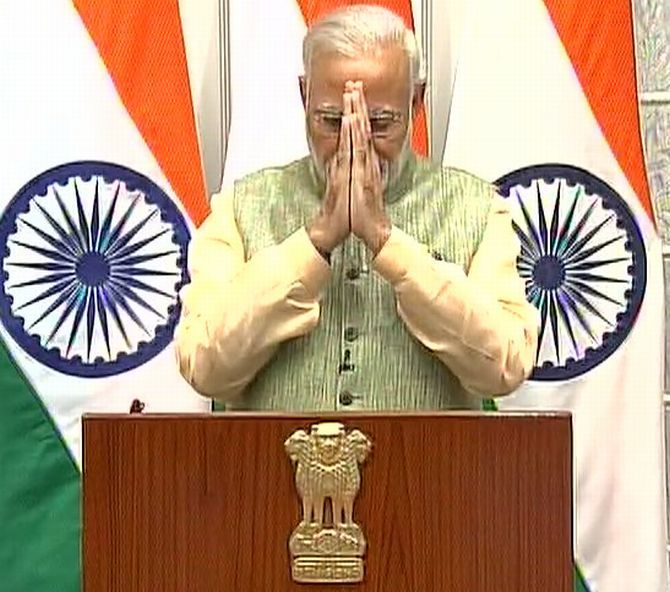

IMAGE: Prime Minister Narendra Modi after his speech to the nation, December 31, 2016.

© 2025

© 2025