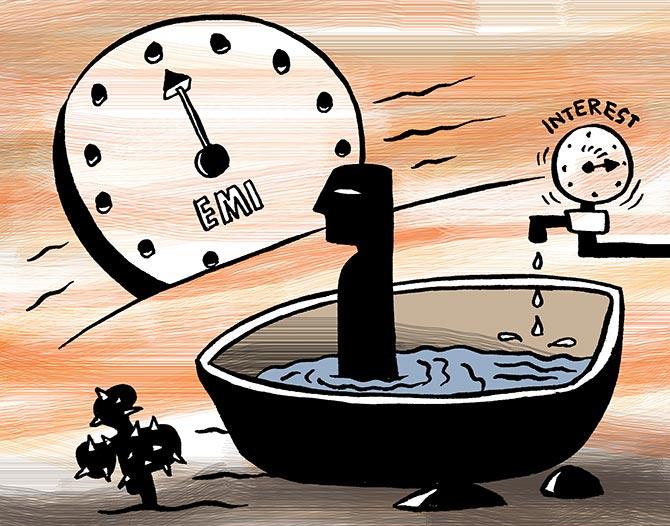

If banks cannot charge interest from borrowers during the moratorium, who will bear that cost?

Should the depositors subsidise the borrowers by foregoing interest on deposits?

In that case, we will turn banking on its head! notes Tamal Bandyopadhyay.

A string of public interest litigations entertained by India's highest court on waiver of interest on interest or compounding interest on loans during the six-month moratorium period, which ended in August, has provoked me to take a close look at the business of banking.

The Reserve Bank of India initially allowed banks to offer a three-month moratorium for all term loans, and later extended it to August 2020 to alleviate the pain of borrowers hit by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Moratoriums are typically imposed in response to temporary financial hardships.

During this period, the borrowers are not required to make any repayment but interest gets accumulated until the end of the moratorium period.

However, those who have moved the court strongly feel that asking the distressed borrowers to pay interest is just not fair.

That banks should not charge interest on unpaid interest or compounding interest or even simple interest.

The Supreme Court has asked the government to clarify its view on the matter by September 28, the date of the next hearing.

Meanwhile, the finance ministry has set up an expert committee to assess the impact of waiving interest payments on loans under moratorium and suggest measures to provide relief to borrowers.

The committee is headed by former comptroller and auditor general Rajiv Mehrishi, and has former Monetary Policy Committee member Ravindra H Dholakia and former managing director of State Bank of India and IDBI Bank, B Sriram, as members.

Just before this, another committee, appointed by the RBI and headed by K V Kamath, former chief of the New Development Bank of BRICS countries, outlined the norms for restructuring those corporate loans that the borrowers are unable to service because of their businesses being affected by the pandemic.

The loans can be restructured by funding interest, converting part of debt into equity and giving the borrowers more time -- as much as two years -- to pay up.

A commercial bank doesn't run currency printing presses. It is a financial intermediary or the so-called pass-through that takes money from depositors and lends to borrowers.

For every Rs 100 it takes from the depositors, it keeps Rs 3 with the RBI in the form of cash reserve ratio. On this, it doesn't earn any interest. Then, at least Rs 18 needs to be invested in government bonds to help the government bridge its fiscal deficit (in reality, banks' investment in such bonds is far higher).

Here, return is thin and laced with risks as a bank needs to provide for the so-called mark to market losses, if the price of a bond dips below the level at which it was bought.

The rest of the deposit (Rs 79) is used for giving loans, keeping a margin that takes care of a bank's wage cost, overheads, credit costs (as some loans can go bad) and profitability. Of course, a bank's capital is also used for giving loans.

A bank is a commercial entity. If it cannot charge interest from borrowers during the moratorium, who will bear that cost?

Should the depositors subsidise the borrowers by foregoing interest on deposits?

In that case, we will turn banking on its head!

The RBI will have to rewrite the norms, putting borrowers ahead of depositors.

The focus in banking has always been protection of depositors first.

Incidentally, the depositors earn compounding interest on their money kept with banks. For fixed deposits and recurring deposits, interests are compounded quarterly.

For savings bank deposits too, where interest is paid on the daily average balance kept, it is compounded quarterly and paid every quarter or twice a year, depending on the bank.

The RBI norms stipulate quarterly interest payment to the depositors and monthly debt servicing by the borrowers.

Let's look into the core of the issue. The loan book of the Indian banking system is around Rs 102 trillion.

Add to that the loan book of non-banking financial companies -- Rs 23.5 trillion (as on September 30, 2019, the latest figure available). So, overall, the loan book of the Indian financial system -- covered by the moratorium -- is Rs 125.5 trillion.

Assuming that average interest is 10 per cent, the annual interest cost on the borrowers is Rs 12.55 trillion. This roughly translates into a monthly cost of Rs 1.05 trillion.

Based on this, the simple interest for the six-month moratorium period is Rs 6.275 trillion and compounding interest, slightly more than Rs 6.4 trillion.

So, if the decision goes in favour of waiving the entire interest for the borrowers, the amount will be a staggering Rs 6.4 trillion.

And, if the waiver is for the 'compounding' part of interest, then it's Rs 13,219 crore.

This is, of course, assuming that each and every borrower has availed of the moratorium -- which is not the case.

I must also say that this is a bit of an over-simplification, presuming the interest is paid off right now.

If it gets added to the equated monthly instalments of the borrowers, after years, depending on the tenure of the loans, the amount will progressively rise.

The key question is: If at all, who pays this up?

Who imposed the lockdown that affected businesses or job losses for the borrowers? Did the RBI do this? Or, the banks?

Since the government announced the lockdown, the buck stops there.

Among many other schemes, the government has offered full guarantee for Rs 3 trillion fresh loans being given to the micro, small and medium enterprises.

The bankers have already sanctioned Rs 1.58 trillion by August-end and disbursed at least Rs 1.11 trillion.

The money involved in the case being heard in the Supreme Court -- if it is only interest on interest and settled now -- will be even less than Rs 13,129 crore since all borrowers have not opted for moratorium and not every one of those who have opted needs the support.

The case clearly exposes the inadequacy of appreciation of how commercial entities should function and the role of the banking regulator.

It will create a precedent, encouraging the community of borrowers to try out the legal route for interest rate waiver in future when they are hit by drought, flood or any other calamity.

Instead of loan waivers, we may start seeing interest rate waivers, or even both can run parallelly!

Finally, this will shake the confidence of the investors in banks.

Till now, the quality of loan assets of banks was often suspect, but the intervention of the judiciary in the business of banking will make the investors sit back and question the projected flow of banks' interest income.

Tamal Bandyopadhyay, a consulting editor with Business Standard, is an author and senior adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank Ltd.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025