'Banks are being encouraged to lend instead of parking their resources with the RBI and earn risk-free interest income,' points out Tamal Bandyopadhyay.

Nobody could have asked for more, even in their dreams.

The central bank, yet again, has gone for an out-of-turn cut in its policy rate.

Yes it is a rate cut even though the Monetary Policy Committee was not involved this time, unlike on March 27, when the last rate cut was announced.

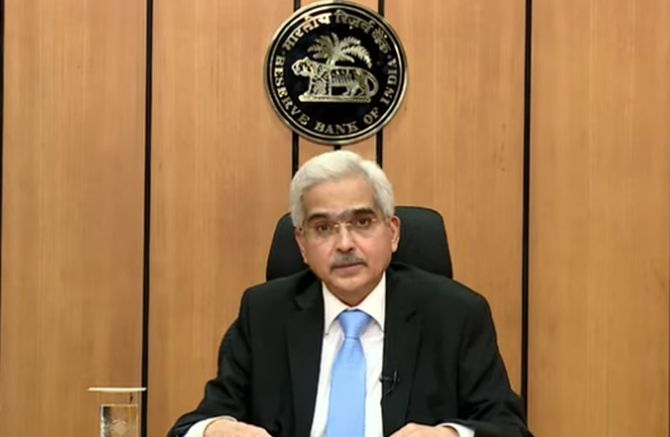

RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das did not need to convene an MPC meeting because this was not a repo rate cut; it's a cut in reverse repo.

That's a technicality. For all practical purposes, since March 27, the reverse repo has become India's policy rate.

Let me explain why.

By definition, the repo is the rate at which the RBI infuses liquidity in the banking system and the reverse repo is the rate at which it drains excess liquidity.

The repo rate is the policy rate, which goes up or down as decided by the majority of the MPC members, keeping in mind the growth-inflation dynamics.

The reverse repo rate, in contrast, is purely a liquidity management tool.

Hence, the RBI can tinker with it; the MPC has no say here.

The story till now is fine, but the repo has ceased to be the lone operating rate in Asia's third largest economy in the past fortnight.

The shift happened after the RBI stopped holding reverse repo auctions post the March 27 policy.

Till that time, the central bank was conducting a fortnightly reverse repo auction and banks used to keep money with the RBI through this route, earning just a fraction below the repo rate.

This means, when the repo rate was 5.15 per cent (till March 26), the RBI would take money from the banks through the fortnightly auctions at 5.14 per cent.

That demonstrated the sanctity of one operating rate -- the repo rate.

This was besides the normal reverse repo window where banks could park excess liquidity at 4.9 per cent.

In other words, till the last rate cut, the 5.15 per cent repo rate was the policy rate and the reverse repo was pegged at 4.9 per cent.

The gap between the two rates (the so-called liquidity adjustment corridor or LAF) was 25 basis points (bps). One bps is a quarter of a percentage point.

In the last policy, the RBI cut the repo rate by 75 bps to 4.4 per cent and brought the reverse repo rate down by 90 bps to 4 per cent, widening the gap, or LAF, from 25 bps to 40 bps.

Now, the reverse repo rate is down by 25 bps to 3.75 per cent.

By stopping the reverse repo auction since then, the RBI had actually cut its policy rate in March not by 75 bps but by 90 bps.

Now, by cutting the reverse repo rate further to 3.75 per cent in a little over a fortnight, the RBI has practically cut its policy rate by 140 bps -- from 5.15 per cent to 3.75 per cent.

The repo is the policy rate when liquidity is tight in the system and reverse repo dons the policy rate mantle when there is excess liquidity -- which is the case now.

How much excess liquidity is there in the Indian banking system? The RBI statement says on April 15, the amount absorbed under reverse repo operations was Rs 6.9 trillion.

Why has the RBI cut the rate? This has been done to stop lazy banking.

Banks are being encouraged to lend instead of parking their resources with the RBI and earn risk-free interest income.

When the savings rate is down to 2.75 per cent, just by parking the money at the reverse repo window, a bank can earn 1 per cent.

The cut in reverse repo will be a disincentive for commercial banks to keep money with the central bank.

The other option before the RBI is fixing a limit on how much money a bank can dump on its reserve repo window.

Instead, what the RBI has done is a rate cut, by stealth.

Historically, the gap between repo and reverse repo has varied between 25 bps and 300 bps.

It was 25 bps till the March policy. During uncertain times, it goes up.

For instance, in 2009, during the global financial crisis in the aftermath of the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., it was widened to 300 bps.

Das has said there is scope for action as the inflation is on a downward trajectory.

He has also reiterated that the RBI would monitor the evolving situation continuously and use all its instruments to address the daunting challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic.

We will wait and watch. For now, the governor has used the reverse repo instrument smartly.

He can do it again and widen the gap between repo and reverse repo further.

For the record, the RBI introduced repo as a liquidity management tool, signaling a fundamental change in the conduct of the monetary policy, in June 2000.

The use of repo and reverse repo marked a migration from the direct instrument of monetary control such as bank rate to indirect instruments in a market-based economy.

As a prelude to that, an interim liquidity adjustment facility or ILAF was introduced in April 1999.

Tamal Bandyopadhyay, a consulting editor with Business Standard, is an author and senior adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank Ltd.

© 2025

© 2025