The short-lived strike by Air India employees makes one thing clear: the days of rampant trade unionism are over, says T N Ninan.

The short-lived strike by Air India employees makes one thing clear: the days of rampant trade unionism are over, says T N Ninan.

The tone of discussions on TV talk shows, where the airline's union representatives were on the defensive, and the public focus on the plight of hapless passengers leave little room for doubt.

The country's mood has changed when it comes to industrial action. The official statistics say it too, loud and clear.

Guess how many cases of industrial action there were in all of 2009 - a grand total of 69, counting both strikes by workers and lock-outs by managements. The number of man-days lost was 2.27 million. Back in the heyday of unionism in the 1970s and the 1980s, it used to be 10 times that number.

If there is a single episode which made the tide turn, it was the prolonged strike in Mumbai's textile mills that Datta Samant led in 1982.

That ended with almost none of the mills re-opening, except under government control - only for the majority to shut down anyway. Workers in Mumbai learnt the hard lesson that those in Kolkata were already absorbing: if you pushed things too far, you not only would not get a wage hike, you would lose your job. There hasn't been another such industry-wide showdown in 28 years.

It mattered that the courts changed their stance. Time was when political parties and unions could call bandhs and bring a whole state to a standstill. You could protest all you liked about the inconvenience and the loss of production, indeed the lawlessness of it all, but no one would listen.

Now, the Kerala High Court has cracked down against bandhs, and been backed by the Supreme Court. There has been a similar change of mindset on other labour issues. Time was when the Supreme Court asked Air India to absorb nearly a thousand contract workers (cleaners, canteen staff, etc) as permanent employees of the airline.

Now the same court has reversed its position on contract workers, although the law remains unchanged.

The arrival of competition has made a difference too. Monopoly unions in banking, telecom and insurance could hold their customers and the entire economic system to ransom.

But as in aviation, the entry of private players has given customers a choice and weakened the unions' coercive power. Finally, people have accepted the ups and downs of the business cycle, and job mobility (instead of lifelong jobs), as facts of life. The laws have not changed, attitudes have.

The pendulum could swing too far the other way, as there is growing evidence of employers not paying minimum wages, denying job security, and the like. Indeed, the Air India boss may have over-stepped with large-scale sackings. But, for the moment, managers find they are swimming with the tide.

Post-script: A word on labour statistics. The official figure for the country's workforce is 459 million, 268 million of them in agriculture. Of the remaining 191 million, only 26 million are said to be in the "organised" sector (establishments that have at least 10 employees).

Yet, the provident fund system (which covers establishments that have at least 20 employees) covers more people, not less as you would expect - 45 million members, in over 570,000 establishments. Since the PF system deals with real contributions made every month by members, its number must be more reliable than the figure for the organised sector, which must be a hopeless under-estimate.

Against this, the country's largest trade union organisation (the Marxist-affiliated Centre of Indian Trade Unions) has a verified membership of 2.6 million - a tiny fraction of the workers in the organised sector.

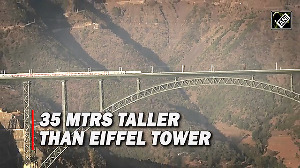

Image: Air India employeesPhotograph: Sahil Salvi

© 2025 Rediff.com -

© 2025 Rediff.com -