In prior elections, not only have opinion poll forecasts been very different from the results, the error margin has increased over time.

One need only look at the charts that show the Sensex half a year before and after the results day for the last six elections. The markets did not change direction in any, says Neelkanth Mishra.

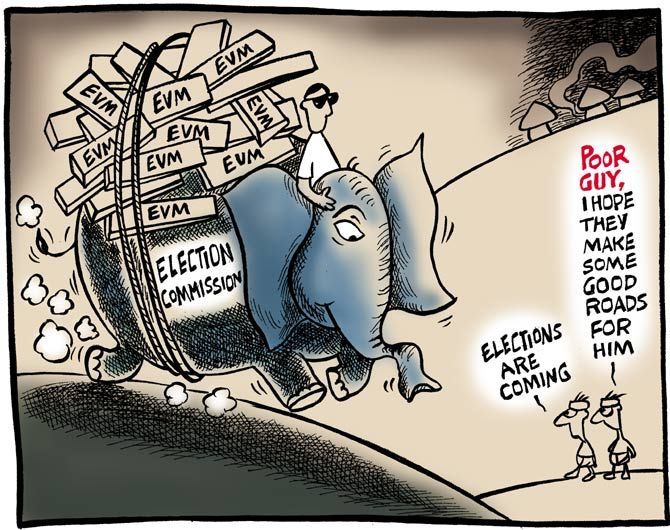

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

What do you think will happen in the elections?

This is a question that comes up in every investor meeting these days.

I usually start by explaining that elections have no lasting impact on markets: One need only look at the charts that show the Sensex half a year before and after the results day for the last six elections.

The markets did not change direction in any.

In two, of which more famously in 2004, there was volatility on results day, but soon enough prior trends resumed.

In fact, despite investor apprehensions of significant volatility around election results, four of the past six elections did not see any meaningful rise in volatility either.

That elections have no lasting impact on markets is an observation, and not the result of analysis: An analytical framework can be debated for accuracy and bias, but an observation is hard to dispute.

I then bring up the unpredictability of electoral outcomes (to show that pre-results positioning on any outcome could be tricky): In prior elections, not only have opinion poll forecasts been very different from the results, the error margin has increased over time.

Whereas the error margin was 10 to 20 seats in 1998 and 1999, it widened to nearly a hundred seats in 2014.

Contrary to the false sense of certainty that opinion polls seem to provide, psephologists working for political parties, some of them surveying tens of thousands of potential voters every few weeks, and with serious skin in the game, generally talk of a range of seats they may win in a state.

Uncomfortable as the width of these ranges may be, these are more realistic.

Outcomes after all depend not just on voter preferences, but also voter turnout.

We recently discovered, for example, that in some constituencies of Bihar, only 30 per cent of registered men turn up to vote, as against 70 per cent of registered women voters.

Bihar is rapidly catching up to Kerala in outward migration to West Asian countries, explaining the drop in male turnout; better security provisions around elections explain the rise in the turnout of women.

While this has not been studied yet, women are expected to be less caste-loyal when voting than men.

Further, some popular leaders and parties account for a substantial share of votes in a particular constituency, even though their aggregate votes are rounding errors at the state level.

Imagine a forecaster building a forecasting framework: How would one adjust for such changes?

Let us run through four key reasons why markets should be unaffected by the results of general elections.

First, since 1991, the Centre has whittled down its economic presence, and most major reforms now need to be done at the state level, which have different election cycles.

Constitutionally, state governments are empowered with control of land, labour, environment, power distribution, and municipal administration: The issues that matter most to corporations.

States altogether employ four times the number of personnel that the central governments do, and collectively spend nearly 90 per cent more than the Centre.

Civil servants’ reluctance in recent years to leave their positions in state governments and move to the centre for deputations is partly driven by the drop in the discretionary powers of the central government.

Second, differences between the ideologies of political parties in India are generally social and not economic.

This is not to say there are no differences: On issues such as fiscal discipline, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) governments have shown more discipline than others.

However, in times of stress even the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) and third front governments have attempted consolidation, and the NDA has also given in to distributing handouts when politically necessary.

Most importantly, all political parties have to navigate the rigid bureaucracy when driving institutional change.

Third, the economy and market are not the same.

More than half of the revenues of companies in the mainstream indices are not India-linked.

This includes export-driven sectors like IT services, pharmaceuticals and automotive companies and component makers.

In sectors such as metals and petrochemicals, too, profits are linked to global trends, even though the bulk of the volumes may be consumed locally.

These are unlikely to be affected by a change in government.

Further, even the revenues that are linked to India are mostly in private banks and consumer firms that have remarkable stability in growth: Steady market share gains of private sector banks that allows them to sustain 20 per cent growth is likely to stay unchanged irrespective of the government in power.

Fourth, more than 40 per cent of the free float of the Indian equity market is owned by foreign investors, who have nearly complete freedom to enter and exit.

Their views on the market are affected by other assets they can invest in globally, bringing in the impact of trends in global financial markets.

The recent surge in the Nifty, for example, which many believe was due to falling chances of an unstable government at the centre, was largely due to a flight to safety by global investors.

Two-month flows into India hit a record $7 billion as investors responded to higher uncertainty in global growth (India is considered a relatively insulated economy), and the fall in sovereign bond yields in the US reduced concerns about the expensive valuation of Indian equities.

A study of the market around elections since 1996 throws up several other market-influencing developments: The Asian and Russian crises, sanctions after the second Pokhran blast, the build-up and bursting of the dot-com bubble, the synchronised upturn in global economy and markets between 2004 and 2008, the recovery from the financial crisis in 2009 and the taper-tantrum in 2013.

The current year may have its own share of global stimuli.

There can be pockets of the market that get impacted by elections, like the stocks with smaller market capitalisation and lower trading volumes: (small-caps and mid-caps).

These have greater exposure to the Indian economy, have higher domestic ownership (that is, lower foreign ownership), and given the lack of liquidity in trading, can be significantly more volatile due to a change in sentiment.

But for the rest, interesting as it indeed is to discuss political trends and scenarios, it may be prudent to look through the developments around May 23, when election results are to be announced.

Neelkanth Mishra is co-head of Asia Pacific Strategy and India Strategist for Credit Suisse.

© 2025

© 2025