'The much-awaited decision could be a welcome change at a time when the Indian armed forces are crying for self-reliance and the defence industry is looking forward to more indigenisation,' notes Nitin A Gokhale.

On May 16, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the corporatisation of the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB).

With over 40 ordnance factories under the OFB, it's a huge asset that has been a laggard since inception.

The finance minister was specific, that it wasn't privatisation, but corporatisation.

The establishment would be run like public sector undertakings.

Fifteen OFB units will be corporatised in the first phase.

Overall, the step should give the ordinance factories more autonomy, while enforcing greater accountability.

The shares of the factories would be listed on the bourses, thus bringing in greater transparency in their functioning.

The way ahead is not easy, but a determined thrust could lead to a more profitable restructuring of the OFB.

The issue of corporatisation is not new.

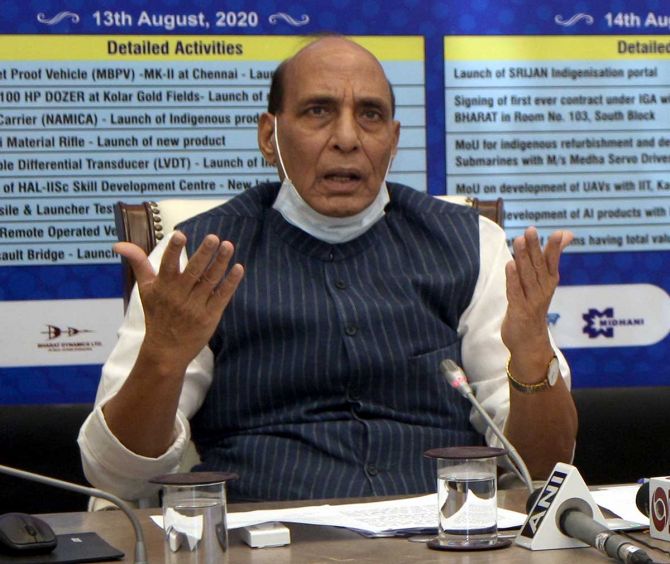

The Modi government wanted it done in its first term but it was not until now -- till Rajnath Singh took over as defence minister -- that this process has gathered pace.

OFB employees have opposed the Centre's proposal of converting ordnance factories into public sector entities to introduce greater professionalism in their management and increase the export potential of defence equipment.

However, OFB employees have opposed the idea for various reasons.

Hopefully, the plan will be executed and followed up in due course for privatisation.

Before getting into the arguments on both sides, it is essential to take a look at the history of OFB and the way it has evolved.

The Indian Ordnance Factories organisation -- a family of 41 ordnance factories under the aegis of its corporate headquarters, Ordnance Factory Board, Kolkata -- is a mammoth industrial setup which functions under the department of defence production of the ministry of defence.

The OFB comprises the world's largest defence equipment manufacturers, producing troop uniforms, tents and boots to parachutes, ammunition, tanks, artillery guns and armoured vehicles for the armed forces.

The OFB is over 200 years old.

It traces its origins to the Gun and Shell factory set up by the East India Company in Cossipore, near Kolkata, in 1801.

Since then it has made steady progress and forms an integrated base for indigenous production of defence hardware and equipment, with the primary objective of self-reliance in equipping the armed forces with state-of-the-art battlefield equipment.

Ordnance factories were set up as 'captive centres' to serve the needs of the armed forces, but have been facing performance issues for a long time.

Concerns have been raised in various quarters over the last few decades regarding the functioning of the OFB which, according to its critics, lacks a professional attitude as required from a manufacturing organisation like OFB.

Today, the board receives annual budgetary support of over Rs 20,000 crore (Rs 200 billion), has over 80,000 employees and holds over 60,000 acres of land.

More than 80 per cent of the OFB's orders come from the army, though the cluster of 41 factories meets barely 50 per cent of the army's requirements.

Once called the 'force behind armed forces', it has lost its lustre because of its peculiar organisational structure.

The present set-up and methods of OFB are inconsistent with the requirements of industry conglomerates that call for agility and flexibility at top managerial levels.

Every decision relating to them, from the modernisation of plants and machinery to entering into joint ventures with other companies, are subject to government rules and regulations, which reduces the leverage and flexibility of a professionally-run company.

Being an arm of the government, the OFB and its factories cannot retain profits and, hence, do not have the incentive to make any.

OFB in its present avatar of a departmental organisation may not be appropriate for carrying out production activities and competing with rivals in the sector who have all the managerial and technical flexibility.

According to the defence ministry, there are a few key issues concerning ordnance factories which impinge on its performance.

OFB has all along supplied products to the armed forces -- the captive customer -- on a nomination basis which has its inherent disadvantages.

Because of monopoly, there is no incentive for OFB to improve the quality of its products or to implement a dynamic system of getting customer feedback on both quality and on-time delivery issues.

Cost of items issued to the armed forces/CAPFs etc form part of its income.

Poor quality of OFB products have been a consistent cause for concern.

It's an open secret that the armed forces routinely take up issues concerning the poor quality of ammunition manufactured by the ordnance factories, pointing out that it has led to several fatal incidents.

The high cost of OFB products due to high overhead charges in OFB, including high maintenance charges, high supervisory and indirect labour charges, are major concerns.

This also results in high overhead charges being loaded onto OFB products, with minimal innovation and technology development taking place.

According to the Additional Controller General of Defence Accounts Report of 2016, the OFB was overcharging the army several hundred crores in cases ranging from battle tanks to clothing to general stores.

In the case of the T-90 tanks built under licence from Russia at the Heavy Vehicles Factory, Avadi, the OFB was charging the army Rs 21 crore per tank, nearly 50 per cent more than what an import would cost.

There is minimal innovation and technology development in OFB.

Generally, there is low productivity of plant and machinery and manpower.

Furthermore, working under the umbrella of government procedures and being the sole service provider for the armed forces, there is no penalty for delayed delivery to the customers.

Over the past two decades, the subject of restructuring/corporatisation of OFB has been examined by various committees.

The T K A Nair Committee (formed in May 2000) suggested corporatisation -- the conversion of the Ordnance Factory Board into the Ordnance Factory Corporation Limited.

It was further observed that maintaining the status quo of ordnance factories as cost centres in a government department would prove expensive, financially and strategically.

With a strong board consisting of senior officials from the government, army, research wings, public sector undertaking and from industry, the corporation can start its long journey of relying on its strengths, revenues and surpluses, for growth.

The proposed structure would also enable appropriate future changes in line with the dynamic, fast-changing global environment related to the production of defence goods.

In 2004, the Vijay Kelkar Committee also recommended the same, suggesting that it be accorded the status of a Navratna, along the lines of BSNL.

Corporatisation does not necessarily mean privatisation.

It was observed that the formation of a corporation alone would ensure that ordnance factories get the desired functional autonomy and make them accountable and responsible for their operations and performances.

Later, in April 2015, Vice Admiral Raman Puri Committee observed that it is essential to change the current functioning of OFB as an attached office of the ministry and a budgeted entity as it is completely incompatible with the modern methods of production and quality control.

It recommended corporatising the OFB and splitting it into three or four segments, with each one specialising in a distinct area like weapons, ammunition and combat vehicles.

The first moves to end the OFB monopoly came last year when the government notified 275 non-core items which the armed forces could buy from the open market.

In the past, the services had to buy these items exclusively from the OFB.

The first move to open up the OFB was started in September 2016 when it was assessed that the OFB was not meeting the Army's requirement.

This led to a series of policy decisions that gradually came to the present stage: whittling away the OFB's monopoly.

The corporatisation of ordnance factories was listed as one of the 167 'transformative ideas' to be implemented in the first 100 days of the Modi government's second term.

These ideas were proposed in early July based on the recommendations of the sectoral group of secretaries in consultation with the relevant groups of ministers.

OFB's top officials were called for a meeting with Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and ministry officials on July 18 last year, during which a decision to finalise the plan was taken.

Officials say a Cabinet note to give effect to corporatisation had been prepared and circulated to stakeholder ministries for consultation.

Finally, on the call given by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on May 12 for a 'Self Reliant India' amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on May 16 announced that the Ordnance Factory Board would be corporatised.

However, Sitharaman emphasised that it did not mean privatisation and the corporatised OFB will remain under government control, indirectly implying the ministry of defence having control over its functioning on the lines of defence public sector undertakings.

The much-awaited decision could be a welcome change at a time when the Indian armed forces are crying for self-reliance and the defence industry is looking forward to more indigenisation.

Nitin A Gokhale, one of South Asia's leading strategic analysts, is an author, media trainer and founder of the specialised defence-related Web sites BharatShakti.in and StratNewsGlobal.com.

His books include Securing India, the Modi Way; Rashtriya Rifles: The Home of the Brave; Beyond NJ 9842: The Siachen Saga; 1965: Turning the Tide: How India won the War; Sri Lanka: From War to Peace, The Hot Brew and R N Kao: A Gentleman Spymaster.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025