'By the time he gets done, he'll not only be the best player of his generation, but the best ever.'

'It'll take another 100 years for someone to break his records.'

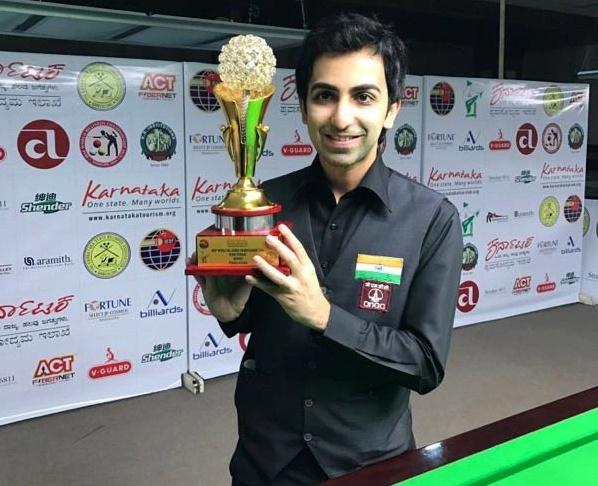

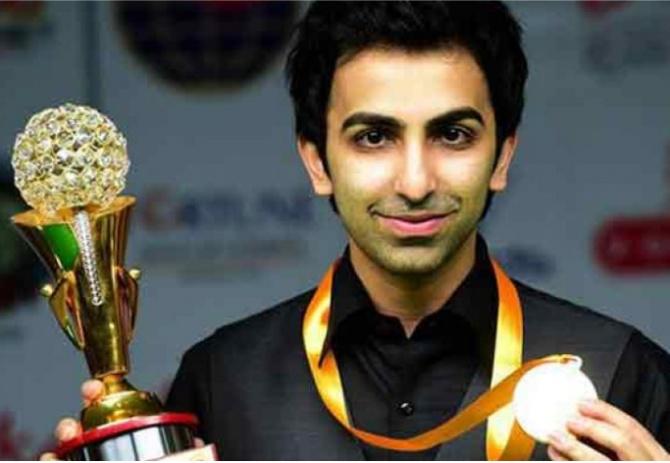

Dhruv Munjal salutes the magnificent Pankaj Advani.

Ask Pankaj Advani about some of his sporting heroes and he reels off names of some genuine heavyweights.

Dhyan Chand, Roger Federer, Michael Schumacher -- athletes who not only dominated their sport but pretty much reset the limits of what's humanly possible.

"For me, the greatest inspiration is people who become the very definition of their sport... athletes who raise the bar and become fine sporting ambassadors," he says.

Advani is one of the gentlest of souls you'll ever come across, but behind the unperturbed, smiling exterior is a man obsessed with being the best, a fierce competitiveness that marks him out as such an elite athlete.

How else do you explain the journey of a man who has won 23 world titles across snooker and billiards over the last 16 years, and remains committed to winning more, still eager to further a legacy that already seems unimaginable to surpass?

"I guess this is the only thing in life I'm good at, so I'm just making the most of it," he jokes self-deprecatingly.

Given its relative obscurity in India, snooker or billiards seems like a slightly odd choice for a sporting career.

The two are still seen as either a domain of the elite, or a sport played idly in shady basements at per-hour rates.

Irrespective of how you start out, stellar careers in the sport are rare. But then so was Advani's talent.

As a 10 year old shadowing his elder brother at snooker parlours in Bengaluru, Advani's potential was discovered early.

Among the first spotters was Arvind Savur, a four-time national champion in the 1960s and 1970s, and a giant in billiards circles.

After watching the young Advani stroke the ball with immaculate perfection on a small table, Savur decided to ring his mother and take him under his wing.

There was just one problem: The boy was just too short for the full-sized table Savur had at home.

"I actually had to send him back. And hearing that, he just broke down," recalls Savur. Not one to give up, Advani, having gained a few kilos and four-and-a-half inches in height, returned a year later.

"I had given him certain exercises and he did them daily. Once he could reach the table, I knew I was looking at a national champion, possibly a world champion," says Savur.

By the time he was 15, Advani was slaying seasoned champions like Geet Sethi, Yasin Merchant and Ashok Shandilya -- many of them Savur's own pupils.

Advani still takes the fitness aspect of his game very seriously. Despite his being a sport of immense concentration and little physical strength, Advani says that strong mental conditioning is only possible with adequate physical exercise.

"While you don't need to build muscles, you need a lot of flexibility and core strength. It's not easy being on the table for four hours straight if your body isn't in the right shape," he says.

Advani's dominance also reflects in the fact that in a country where cue sports are yet to go mainstream he is probably India's most decorated sportsperson ever.

Apart from all his world titles, Advani, still only 34, has already won a Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna (2006) and also been awarded a Padma Shri (2009) and a Padma Bhushan (2018).

For all his victories, Advani reckons that his biggest achievement has been representing India -- a major reason why he considers his billiards gold at the 2006 Asian Games in Doha one of his more memorable wins.

"Because I play an individual sport, some people think I'm playing for myself. But even then, I have the Indian flag next to my name. And that gives me the greatest satisfaction," says Advani.

This fulfilment has arrived after years of hard work, a fact that, amid all the revelling in Advani's glorious success, sometimes gets overlooked.

Advani was born in Pune, but spent his early days in Kuwait. His family's return to India -- and subsequent settling down in Bengaluru -- was fortuitous.

In 1990, while they were on vacation in the US, the Gulf War broke out and the Advanis could never return to Kuwait. Advani's father chose Bengaluru as their new home, primarily for the city's cool climate.

The anguish of abandoning home and moving cities almost overnight was followed by the passing of Advani's father two years later.

"I was too young to understand what was happening at the time, but it was unbelievably tough for all of us. That is when Shree (his elder brother) took on that extra responsibility," says Advani.

Shree, in fact, has been a constant presence in Advani's life. A sports performance psychologist based in Australia, Shree helped his brother bounce back from a terribly difficult phase in 2006, when Advani, suffering from a dip in motivation, looked set to give the game up.

"Shree has been able to programme my mind in such a way that I've been able to dream without limits," says Advani.

"And I know many athletes say this, but I don't worry about the number of titles. I'm just an artist trying to excel all the time. That is the mentality I take into every game." He draws much of that positivity from reading books on spirituality.

Such a mindset has enabled Advani to flourish in both snooker and billiards -- a unique mastery that often eludes the most accomplished of cueists.

Cue sports are full of subtle differences: Snooker is all about power and hitting, whereas billiards demands finesse and patience. "He's mentally tough and he's a great learner. That's why he has been able to maintain consistency in both," feels Savur.

Challenges of the mind for Advani were preceded by financial ones. His taking up a "rich" sport meant that his mother had to break a fixed deposit in 1999 for Advani to travel for his first international tournament in the UK.

This, in spite of Savur not charging Advani a single penny in the early years. "When I first started coaching him, his mother told me that she could not afford to get him dropped and picked up every day. I was so impressed with his talent that I didn't mind doing that myself," reminisces Savur.

Is the sport as elitist as people make it out to be? The question always leaves Advani confused. "It's weird," he says, "On one hand, so many people play pool as a recreational activity in parlours.

On the other, they say the sport is inaccessible. So I myself don't know what the perception really is." But it's not as expensive as people think, he maintains.

"In terms of personal equipment, all you need is a cue, which you only have to change after five or six years. So it's not that unaffordable -- most of our champion cueists have come from middle-class backgrounds."

Now that Advani, much like his idols, has set the bar impossibly high, he is keen to take his ambassadorial role more seriously.

He announced the launch of Cue Sports by Pankaj Advani earlier this year, an academy that will have branches in different schools across Karnataka. "It's just my way of promoting the sport, making it more accessible."

Which doesn't mean that Advani will be leaving the table anytime soon. In recent years, he has chosen his tournaments carefully, and practice has been designed in a way to maximise quality -- all indicative of a clear focus on longevity.

So much time away from home, after all, has denied Advani the chance to pursue some of his interests outside of snooker and billiards.

Like dance, he reveals, adding that he was offered a dance reality show a few years ago, but had to turn it down because of his busy schedule. "I'm passionate about it, but have never had the time to learn a particular form. Probably once I'm done playing," he smiles.

Advani hopes to continue for another decade, a period that can easily see him win another 10 world titles, feels Savur.

"By the time he gets done, he'll not only be the best player of his generation, but the best ever. It'll take another 100 years for someone to break his records."

© 2025

© 2025