| « Back to article | Print this article |

Sochi Olympics: At last women ski jumpers prove their point, make history

When US ski jumper Sarah Hendrickson sped down a snow-covered ramp and hurtled into the air at 90 km per hour, a piece of Olympic history was made in the Russian mountains on Tuesday.

Ninety years after the first male ski-jumpers competed at a Winter Games, women were finally granted the chance to prove their mettle in one of the ultimate sporting tests of power, technique and sheer daring.

Women fought lawsuit for the right to compete

For years they were told the sport was too risky, that there were too few top-class women competitors, or even that the impact of landing could damage their fertility. A group of US, Canadian and European women fought an unsuccessful lawsuit for the right to compete at the last Olympics in 2010.

But all that frustration was consigned to the past when Hendrickson became the first competitor to rise to her feet, stretch out her hands behind her and take off down the hill at RusSki Gorki in the mountains above Sochi.

'Every woman who is here is part of history'

"It was an amazing feeling. I was standing at the top, and processing all that was pretty surreal," Hendrickson, the 2013 world champion who suffered a knee injury before the Games and ended up in 21st place, told reporters.

"Every woman who is here is part of history," said Evelyn Insam of Italy, who finished fifth in a contest won by Carina Vogt of Germany.

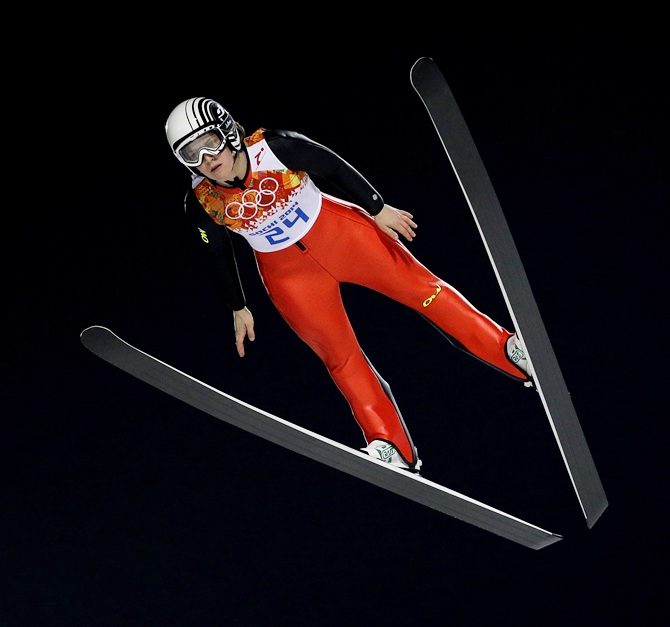

The spectacle is gripping. Seen from the stands, the competitors are distant specks in the misty night air as they shuffle on to the starting bench, point their skis downhill and set off, leaning forward and rapidly gathering pace until the moment of take-off.

'It's a feeling of freedom'

For more than three seconds they are airborne, straining forward with their upper bodies until they are almost parallel to the skis, which are crossed in a V for maximum lift.

"It's hard to describe, it's a feeling of freedom, you feel no support in the air and everything depends on yourself," said Daniela Iraschko-Stolz of Austria.

She took the silver medal with a second jump of 104.5 metres - only one metre shorter than the best effort of the men's gold medallist, Kamil Stoch of Poland, on Sunday.

France's Coline Mattel won the bronze, edging out Japanese teenager Sara Takanashi, the pre-event favourite.

'Sara Takanashi is giving us strength and courage'

The only consolation for the 17-year-old Takanashi was the loyal support of a group of fans sporting full-length white winter jackets with "Sara Takanashi Supporters, Kamikawa, Japan" in pink letters on the back.

"History is being written," said Toshie Ikaya, 46, with Japanese flags on both cheeks and pinned to the back of her baseball hat.

"Sara Takanashi is giving us strength and courage. She's providing encouragement for those who are coming next."

'It feels like we've arrived'

While US women finished well down the field, with Jessica Jerome in 10th place and Lindsey Van in 15th, there was satisfaction in getting to the Olympics in the first place.

"It feels like we've arrived, finally. We've shown we belong here and we put on a great show," said Jerome, whose father Peter founded Women's Ski Jumping USA and has been a tireless lobbyist to bring the sport to the Olympics.

'Fighting for all women in all sports'

For Deedee Corradini, president of the group, there was a wider significance in the long road to Sochi.

"We were really fighting for all women in all sports and hopefully in all aspects of life. Hopefully we have taught other young girls and young women around the world that if you really are persistent and never give up, fight hard...then you can achieve your dreams," she said.

"So go for it. That's what we hope."

Beyond normal

For many of the women, jumping from the so-called Normal Hill at the Olympics is not the end of the journey: they want to join the men in taking off from the even more daunting Large Hill, and in a team event.

"Maybe another competition on the big hill would be nice," said Italy's Insam.

By the time of the next Winter Olympics, in South Korea in 2018, she hopes she will get that chance.

© Copyright 2024 Reuters Limited. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Reuters. Reuters shall not be liable for any errors or delays in the content, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.