| « Back to article | Print this article |

Love lies in the sound

Love lies in the sound. That symphonic bellow of engineering excellence squeezed, by a man in a helmet using a foot and two thumbs, into a flawless note of phenomenal precision. That deafening roar grabbing you by the guts and by the loins, by the throat and by the knees, by the ears and by the heart.

The first time you truly hear the primeval holler of a Formula One engine at full tilt, your jaw will drop, your pulse will pound like a gorilla on cocaine, and your nether regions will instantly, if only momentarily, stiffen and throb with the dramatic suddenness of utterly unexpected and overwhelming arousal. Embrace it.

And as you get sucked into the sport -- headlong, like a scrap of rival debris hoovered fatally up by an exhaust propeller -- your ears and newly formed allegiances take over and you begin to ascribe voices and personalities to those dizzying sounds. The near-iambic constantly mounting gallop of a Ferrari turning into a scalded screech when pushed defiantly and deliciously past permissible limits; the fighter-jet whinny of a McLaren banking around the curves, swallowing them with inch-perfect accuracy; the Renault clearing its throat DarthVaderistically as its launch-control thrusts out a garrulous burst of power... You listen carefully, and, like a smitten band-aid hanging on to every arpeggio a guitar-god can toss out, you eulogise.

The intoxicating rise of the RPM to impossible Robert Plant heights; the quick but vital hiccup like a sharp gasp of sexually satiated breath as gears are changed; the determined guttural growl of a machine valiantly defending position around a particularly twisty chicane. Rock and roll.

(This feature first appeared in Man's World magazine)

Maybe it is about sound

For me, as with most Formula One fetishists, that sound came later. First came a German name flashed all over copies of Sportstar I borrowed from the neighbourhood library to read about Boon and Becker (and to gaze devotedly at Graf and Sabatini).

It amused me that Benetton, which made tee-shirts my mother bought me, had its own racing team, and that they were actually winning, beating the guys who made sportscars my father coveted. And it was apparently all because of this young fellow with the cobbler last-name. I didn't watch a full Formula One race till a few years later, but I soon knew that name and whimsically, without much at stake, decided it would be worth rooting for.

Maybe it is about sound; maybe I just liked saying it out loud. That first name, two common but perfect syllables, rhyming with 'cycle', which seemed, in those Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar days, racy enough; the last name somehow like both sneaker and machine, the end said as if to rhyme with the grrrr of an unforgiving engine... Hokum, yes, scribbled vainly in hindsight to try and make sense of that initial besotting, but somehow the name -- like that of the man who made me wake up at dawn to watch the Chicago Bulls win and win again -- instantly appealed and I chose his corner.

It wasn't one of those too-good-to-be-true names of sporting greats that seem conjured up by fanciful balladeers -- like 'Tiger Woods' or, more unbelievably still, 'Valentino Rossi' -- yet the words 'Michael Schumacher' had more than enough magic around the edges to win me over.

Cunning was as vital as the speed of the car

I did naively imagine, however, that Formula One was all about speed, about finding control and pushing the envelope and sometimes going over the edge and, um, dying, but essentially about pressing the accelerator harder and more foolhardily than the guy next to you.

The first time I actually watched the sport, the highlight package of a race, it immediately set me straight. Belgium, 1995. That fellow Schumacher is being pursued by a Briton named Damon Hill and the commentators are confounded as to how, despite being over five seconds a lap slower than Hill, the German driving on worn-out dry tyres on a wet racetrack, stays ahead lap after lap, eventually winning. That bit of canny racecraft, not to mention all that talk about tyres and pitstops, began to inject F1 heroin-deep into my spectatorial veins.

The cars stop, you see. These, to me, were revelations: the fact that the cars have to stop for fuel and tires; that these stops are done in half the time it takes me to type this sentence; that they can stop whenever they see fit; and, most critically, that stopping would probably lose them their place on the track.

This instantly implied a need for strategy, and as I went from mildly curious observer into regular viewer, I learnt this cunning was as vital as the speed of the car and the excellence of the driver. The sport demands it all: skill, smarts, speed, strength, supervision, stacks and stacks of sestertii.

F1 is the single most glamorous sport in the world

Oh, and skirts.

Given the astronomical cost of participation, extreme exclusivity and, morbidly enough, the fact that people can actually lose their lives on the track, Formula One is the single most glamorous sport in the world. Basketball players might find themselves on mass-produced sneakers and footballers may make more money (every now and then), but Formula One is a black-tie sport, glitzier than they could ever hope to be -- and F1 knows it.

It is gladiatorial gamesmanship from a different time. Obscenely exorbitant by definition, it sprawls luxuriantly across acreage and airspace, revelling in its own preposterous existence, an utter improbability given our politically-overcorrect, increasingly green world stressing on the practical. And, as befitting an unreal sport given to excess, it likes its women.

A brigade of striking pit-girls can be seen on a Formula One grid to this day, but that pales in comparison to the past. Well-documented legend has it that sensational beauties would coax their way into an F1 paddock the same way they now try and work their way behind the velvet rope at an impossible-to-enter club, and only the most ravishing need apply. Or the boldest.

Back in the shamelessly hedonistic 70s, pretty young women could enter the land where the Dom Perignon flowed unfettered only after lifting their skirts and displaying their knickerslessness.

F1 is inherently about characters

And many would doubtless have been charmed by a driver called James Hunt. Hunt began his career with Hesketh, a self-funded team run by a whimsical Baron of the same name, a team with a teddy-bear on its cars in lieu of sponsor logos. "Sex: Breakfast Of Champions," said the badge on Hunt's overalls, the driver epitomizing F1's playboy lifestyle above and beyond any imagined cliche.

There was eccentricity -- he took his Alsatian to dine with him at London's finest restaurants -- and excess, in the form of women, drugs and sleeplessness. Yet not just did he win 6 races in 1976 to pick up a World Championship, he also discovered a driver named Gilles Villeneuve, widely considered one of F1s very finest. And so what if Hunt went to formal McLaren galas in jeans and without footwear?

Formula One, like any sport to do with individual achievement and milestones, is inherently about characters. And while the same can well be said of, say, tennis, the perennially contrasting facets of personality sought out by motorsport -- ruthlessness, consistency, guile, hunger, bravery, pragmatism, recklessness, caution, loyalty, opportunism -- as well as, perhaps, the fact that their heads rattle around inside those helmets for an awfully long time, bring out some truly unique individual characteristics, gifted young men each finding their own zone, somewhere between kamikaze and zen.

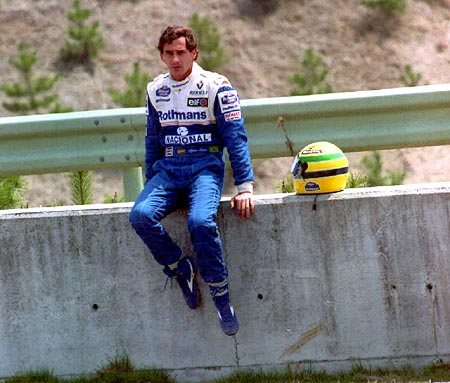

For every mercurial Ayrton Senna, there is a silken Alain Prost, and amen to that: for the sport would be far poorer without all its magnificently extreme men in their flying machines.

It is about winning, and about racing

And so it is about the men who pilot, and those that build the machines and those who let the machines be built. It is about those that commit to impossible victory and those that settle for second place. It is about ideal racing lines and impeccable technique, and it is about crashes and shunts and embarrassments.

It is about the girls who come and egg drivers on, and about the drivers who win races in memory of their mothers. It is about circuits steeped in history that reverberate with the thunder of races gone by, and about brand new circuits and virgin tarmacs with the promise of epics to come.

It is about being so near and yet so far, and about obliterating the competition with a dominance so severe the ignoramuses call it boring. It is about glory and about gluttony. It is about luck and about destiny. It is about winning, and about racing.

And, as I imagine a young lad of today reading about Formula One, dominated by a company that doesn't make racecars, with a grinning young German driver breaking all sorts of records, it is also about going round and round in a blessedly infinite loop.