| « Back to article | Print this article |

After 'Rush', a film on F1 safety hits the screens

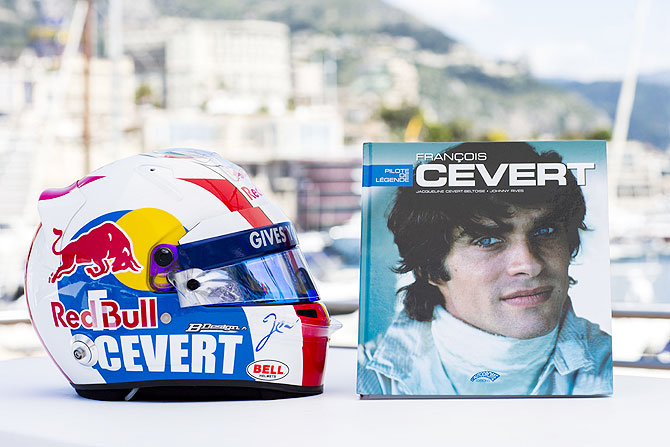

Francois Cevert had the most piercing blue eyes, the presence of a movie star and a Gallic charm that melted hearts wherever he went.

Those eyes, that gaze glimpsed through the visor slit of a 1970s helmet, are still haunting in the Formula One documentary 1: Life on the Limit due to be released in selected British cinemas in January and then further afield.

A pitlane heart-throb, the Parisian was a hero of more carefree times -- one moment escorting Brigitte Bardot or playing the concert piano and the next risking his life in the most dangerous and glamorous of arenas.

More than a decade before Alain Prost captured his first title in 1985, it was Cevert -- Jackie Stewart's friend and teammate at Tyrrell -- who had seemed destined to become France's first world champion.

Instead, at the age of just 29, he died in qualifying for the 1973 U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen.

The sense of what might have been, the waste of so much young talent in those 'golden' years when sex was safe and motor racing frequently fatal, hangs over the film without sensationalism, recrimination or gratuitous gore.

'1' compliments 'Rush' and 'Senna'

"We all know, every one of us, that death is in our contract," Cevert had declared earlier in his career. He knew the risks, loved the sport, lived -- and died -- for racing.

The story of Formula One combines both horror and heroism, evident in the archive footage, and in later years has focused on the fight to reduce the carnage and improve safety as attitudes common enough in the immediate decades after World War Two began to change.

1… has been long in the making, with a preview shown in Austin last year during the first Grand Prix weekend at the Texas track and then at this year's London Film Festival, but the timing looks right.

Anyone who has seen Rush, the Ron Howard movie with Daniel Bruhl playing Niki Lauda to Chris Hemsworth's James Hunt, will be familiar with the dramatic 1976 season and the Austrian's comeback from a near-fatal crash at the Nuerburgring.

The same applies to fans of Senna, the multiple award-winning film about the life and death of Brazilian triple champion Ayrton Senna.

The latest documentary complements the previous two films, connecting storylines and filling in the background with the drama provided by original footage.

'1' charts F1's progress from 1950s insouciance to the modern era

Narrated by German-Irish actor Michael Fassbender, star of X-Men and Inglourious Basterds, and directed by Paul Crowder, 1 charts Formula One's progress from 1950s insouciance to the modern era where drivers expect to walk away from big crashes.

It includes interviews with Stewart, Stirling Moss, Mario Andretti, Jacky Ickx, Lauda and Nigel Mansell as well as more recent racers Lewis Hamilton, Sebastian Vettel and Michael Schumacher.

Formula One's 83-year-old commercial supremo Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley, former president of the governing International Automobile Federation (FIA), also have their say as key players in the battle to improve safety and men who lost friends along the way.

While younger audiences may not be familiar with the history, the fascination for the committed F1 fan lies in the archive material.

We see Jim Clark at home in rural Scotland and witness the shock and confusion on the faces of spectators in the Hockenheim grandstand in 1968 when his death was announced over tinny loudspeakers before flags were lowered.

There is the tear gently rolling down the cheek of Professor Sid Watkins, who died in 2012, as the eminent neurosurgeon and F1 doctor recalls his last conversation with Senna.

Stewart quit F1 after Cevert's death

There is the poignancy of Austrian Jochen Rindt, the only posthumous world champion, asking his wife shortly before his death at Monza in 1970 what one thing she would wish for.

"For you to stop racing," she replies.

Then there is Cevert. The camera follows Colin Chapman, the Lotus team boss who was already no stranger to fatalities in his own cars, pacing anxiously in the pitlane as he sought information from others about the October 6 accident.

"Cevert? Bloody Hell," he sighs.

Stewart did not compete the next day, or ever again in Formula One. He had already decided to quit as champion, with Cevert -- who had not been told of the plans -- set to take over as Tyrrell number one.

"We arranged to send flowers to his mother and to his grave on that date of every year that followed, until she passed away," the Scot, who likened the Frenchman to a younger brother, wrote in his autobiography Winning is not enough.

The triple champion has continued to do so ever since.

'One is always haunted by the past'

Many others had been mourned already, including promising young Briton Roger Williamson who died earlier in 1973 after a fiery crash at Zandvoort in the Netherlands.

The footage of that accident, with the driver trapped in the flaming upside-down wreck while David Purley struggles in vain to rescue him while the race carried on, remains stomach-churning 40 years on. The viewer is spared nothing.

How much has changed since Senna's death in 1994 is emphasised by the opening shots of Martin Brundle running down the pitlane after a terrifying, flying shunt in Melbourne in 1996 that broke his Jordan in two.

He was unscathed, getting back in a spare for the re-start.

A generation of drivers has now grown up that has never suffered the loss of one of their own at a racetrack, nor started a season wondering whose funeral they might be attending before the year was out.

But there can be no complacency even now, with 2014 marking the 20th anniversary of the last driver fatality (Senna). As Mosley, who started the same Formula Two race in which Clark was killed, observes quietly: "One is always haunted by the past."

© Copyright 2025 Reuters Limited. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Reuters. Reuters shall not be liable for any errors or delays in the content, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.