As the island heads for elections, two major factors worry Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

As the island heads for elections, two major factors worry Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

One is the division in the Sinhala vote and the other is the prospect of the Tamils and Muslims voting heavily against him.

Nitin Gokhale reports from Colombo on how Rajapaksa may be defeated.

In less than a week, Sri Lanka's 15 million voters will exercise their franchise in what may turn out to be that country's most important election this century.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa, bidding for an unprecedented third term in office, called for elections two years ahead of schedule in the hope of extending his decade-long tenure.

Till the end of November 2014, Rajapaksa looked set to emerge a comfortable winner in absence of any credible alternative.

However, Maithripala Sirisena, a long-time colleague of Rajapaksa and till recently his health minister, suddenly defected from the ruling combine, breathing a fresh life into the opposition camp.

Sirisena, a staunch Sinhala Buddhist much like Rajapaksa, has rallied the fragmented Opposition and has secured the support of former president Chandrika Kumaratunga and former prime minister Ranil Wickramasinghe, posing a serious challenge to Rajapaksa.

Two major factors worry Rajapaksa. One is the division in the Sinhala vote and the other is the prospect of the minorities -- Tamils and Muslims -- voting heavily against him in Sirisena's favour.

In the 2010 elections, Rajapaksa polled more than double the votes secured by his main opponent, former army chief General Sarath Fonseka in the Sinhala majority areas of the south, central and western provinces. This time, Sirisena has the advantage of the ultra-radical, right wing Sinhala party, the Jathika Hela Urumaya (National Heritage Party), backing him against Rajapaksa and his own background as a long-serving Sinhala leader from a rural background boosting his campaign.

For a clean victory from only the south, a candidate needs 58.3 per cent or 5.25 million Sinhala votes. If Rajapaksa fails to hold on to his 2010 vote share in these areas, he will have to look to make up that loss in the northern and eastern provinces which have not been his strongholds.

In the 2010 presidential election, Rajapaksa got 6.02 million (57.9 per cent) votes secured mostly from the south and the east.

On the other hand, in the 2010 elections Rajapaksa secured less than 30 per cent of the valid votes in the Tamil-dominated northern province.

In the eastern province too -- which has a mix of Muslims and Tamils -- except for Trincomalee district, Rajapaksa failed to get more than 26 per cent of the valid votes.

General Fonseka won more than 60 per cent votes in these areas.

Voting trends in the previous election cannot, however, be a clear indicator of the current position since there is a vast difference between the situation in 2010 and now.

Sirisena's campaign got a boost after a Sri Lanka Freedom Party minister Navin Dissanayake and an influential Muslim party, the All Ceylon Makkal Congress led by minister Rishad Bathiuddeen and Member of Parliament Amir Ali withdrew support for the president and cast their lot with the common Opposition candidate.

The Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, another influential Muslim party led by Justice Minister Rauff Hakeem, has also decided to support Sirisena, after intense debate within the party. Both the Muslim organisations had major grievances over the handling of the anti-Muslim riots last year and the free run that the Rajapaksa government allowed the extremist Buddhist outfit, the Bodu Bala Sena.

However, these parties have been unable to guarantee full support to Sirisena, as some sections are still in favour of Rajapaksa.

Sirisena also needs to make a dent in the Tamil heartland to get ahead of Rajapaksa who appears to have about 20 per cent of the Tamil votes in his favour. Sirisena has not yet spoken a word about the Tamil issue, about the 13th amendment, about reconciliation or about giving Tamils their dignity back.

His manifesto does not even mention the Tamils and their concerns. So far, he has not visited the Tamil areas nor has he spoken about the Tamils.

Although the largest Tamil group, the Tamil National Alliance has decided to support Sirisena, it is not clear if Tamils will vote in sufficiently large numbers to make up for any shortfall that Sirisena may face in Sinhala areas. TNA chief R Sampanthan, announcing the support, said the Tamil question can be solved only in a democratic set-up and not under a dictatorship or a totalitarian system, practiced by Rajapaksa or implemented by the Tamil Tigers under V Prabhakaran when he ruled the roost in the northern areas before being killed in the military operation in May 2009.

Under Rajapaksa, Sampathan said Sri Lanka has inexorably moved towards dictatorship and totalitarianism. On the other hand, Sirisena has promised to restore democracy, Sampanthan said.

Sri Lanka watchers point out that Sirisena has so far offered nothing concrete to the Tamils to fire all of them up. Those who are determined to get rid of Rajapaksa for the sake of restoring democracy will vote, but these may not be the majority who might like to sit at home.

Rajapaksa is assiduously wooing Tamils, both Sri Lankan Tamils living in the northern and eastern provinces, and the Tamils of Indian Origin, living in the plantations of central Sri Lanka.

He has not only toured the north and east more than once, but has made some promises, which will attract those who suffered during the war against terror.

In his manifesto, Rajapaksa said he would appoint a special committee to go into the question of releasing young men and women detained on the charge of collaborating with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

Vehicles and lands seized from the Tamils during the war and after would be returned. To the plantation workers of Indian origin, he has promised that each family will get seven 'perches' of land (enough to build a small house).

Rajapaksa, adept at playing on Sinhala nationalist sentiment, has promised a new constitution, committing himself once again to the unitary status. Against the backdrop of Tamil separatism, Rajapaksa/s promise to establish a domestic investigative mechanism for a probe into the alleged war crimes even while preventing any international scrutiny, appeals to the hardcore Sinhala voter base.

In Colombo, the revulsion against the Rajapaksas and yearning for change is palpable, but the rural vote outside Colombo seems largely behind the president.

Sirisena appears to be a dove who appears to have strange political bedfellows.

,p>There is also a lack of focus and cohesion among the disparate elements supporting Sirisena's campaign. The JHU and TNA are at the opposite end of the spectrum on the 13th amendment; there is also a difference of opinion in the Sirisena camp on the size of the military and its larger than life presence in Sri Lanka.

As the tiny island nation heads towards the climax of an unexpectedly close presidential race, its outcome will be keenly watched in New Delhi and Beijing. New Delhi has been rather unhappy with Rajapaksa of late for playing the China card against India too often.

His refusal to fully implement the Indo-Sri Lanka accord, especially the 13th amendment to the Sri Lankan constitution, does not inspire confidence in New Delhi.

Sirisena perhaps evokes unease in Beijing since the Opposition has spoken out against giving China a free run in Sri Lanka. Either way, it will be worth watching the result on January 9.

Nitin Gokhale is a well-known strategic affairs analyst and long time Sri Lanka watcher.

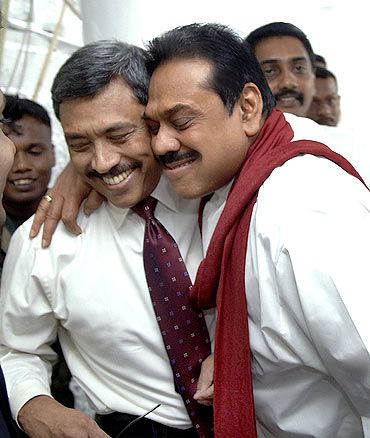

Image: Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, right, hugs his brother Gothabaya, the country's defence secretary. The Rajapaksa family has been accused of running a dictatorship in Sri Lanka, crushing democracy and its opponents. Photograph: Sudath Silva/Reuters

Also read: