The cumulative cost of these three initiatives for social pensions, urban employment and rural allowance would be less than the current peak NYAY estimates of Rs 3.6 trillion, with double the reach of at least 110 million families and fewer expected exclusion errors. There are also several other options to slice the cake, says Swati Narayan.

The Congress Party's poll promise of Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY) has earnestly attempted to shift the pre-election slugfest to real-world priorities.

An injection of one to two per cent of GDP is undoubtedly welcome, in a country renowned for social underspending. But while details are sketchy, unless the straitjacket design of "Rs 6000 per month to 20 per cent of the poorest households" is judiciously fine-tuned, NYAY is unlikely to reap its full potential of anti-poverty or political dividends.

For one, NYAY targets a mere fifth of Indian households. For perspective, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) provides employment to as many homes at a sixth of the cost.

Further, currently a poor Bihari family will receive Rs 72,000 annual NYAY handouts without lifting a finger, which is more than the maximum NREGA wages they can earn across four years. So, it is unclear if the maths of this cash transfer makes prudent fiscal sense. It is also unlikely that NYAY's restricted coverage will sufficiently translate into a pan-Indian vote magnet.

Crucially, NYAY as a "surgical strike" on the poorest quintile erodes the fundamental advantage of Universal Basic Incomes (UBIs) as universal transfers. After all, as Amartya Sen has pointed out, "benefits meant exclusively for the poor often end up being poor benefits."

A recent "Hit and Miss" Development Pathways research, of 38 cash transfers across low and middle-income countries, demonstrates that poverty-targeted programmes ironically miss over half of the poorest quintile of entitled recipients. The exclusion rate of intended beneficiaries ranged from 97 per cent in Rwanda's Vision 2020 which used community targeting to 44 per cent in Brazil's Bolsa Familia even with the simplest means-test.

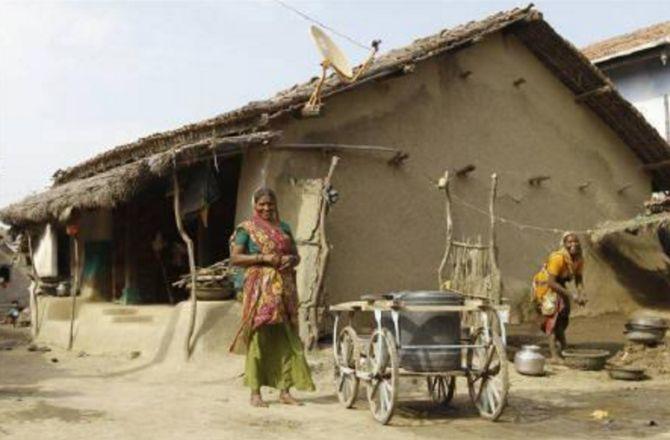

Similarly, NYAY's centralised income cut-offs especially in a country with entrenched rent-seeking is likely to increase the vulnerability of the poor to middlemen. In the last five years, for example, four of every five families with starvation deaths, predominantly dalits, adivasis and minorities, were invariably denied their eligible subsidies.

NYAY too, if opaquely targeted, even with the best of "data science", is unlikely to stem this inhuman starvation in the sweltering heat of rural oppression. Instead, lucid universal "categorical targeting" increases the agency of beneficiaries to be aware of and demand their rights.

Georgia's Old Age Pension paid to all the elderly or Mongolia's universal Child Money Programme for all children under 17 years, had error rates of less than two per cent.

Therefore, rather than experimental pilots, the time is ripe to expand time-tested lifecycle safety nets, championed by social movements for decades, which could be neatly dovetailed into NYAY. These could include a diverse basket of cash transfers.

For instance, while NYAY can subsume social pensions the lifeline must also be universalised. Currently, more than half of the 160 million elderly, widows and differently-abled persons are excluded as only those below the poverty line (BPL) or income thresholds are eligible.

Worse, the Centre pays only an insulting Rs 200 per pensioner each month at a tight-fisted 0.04 per cent of GDP, among the lowest in the world. Instead, as illustrated by Jean Drèze, one option is for NYAY to provide individual rather than household entitlements to all pensioners of at least Rs 1200 per month.

The second crying need, especially after the suppressed job survey pegs unemployment at its highest peak in 45 years with women acutely impacted, is an urban employment guarantee akin to NREGA. Recently, the victorious Congress in Madhya Pradesh has already introduced a scheme, modelled on Tripura and Kerala. A similar nationwide urban guarantee can be rolled out at the proposed national floor minimum wages.

Lastly, it is paramount to halt starvation deaths. While the National Food Security Act (NFSA) feeds 75 per cent of the rural population, due to pervasive corruption, elite capture and Aadhaar, acutely marginalised families remain vulnerable to exclusion. On the other hand, Odisha, West Bengal and Chhattisgarh with universal coverage, have had fewer deaths. So, the NFSA can be universalised solely in rural areas or left-out families compensated with a cash allowance.

The cumulative cost of these three initiatives for social pensions, urban employment and rural allowance would be less than the current peak NYAY estimates of Rs 3.6 trillion, with double the reach of at least 110 million families and fewer expected exclusion errors. There are also several other options to slice the cake.

However, one aspect of NYAY which is insufficiently appreciated is the transfer to female heads of households, as highlighted by Priyanka Gandhi, unlike the BJP's farmer support PM-KISAN. Given that intra-household distribution of resources in India, including food, is heavily gender-biased, the three proposed NYAY variants will further strengthen the support for poor women -- to tide over women's disproportionate brunt of unemployment, care-giving of the elderly and household kitchens.

In any case, the mere announcement of NYAY on the back of PM-KISAN heralds a welcome new competitive chapter in electoral politics to prioritise welfare. This alone is a giant leap forward. Now the electoral pulse of the nation will determine the verdict on NYAY and its potential variants -- to cash in on time-tested lifelines.

Swati Narayan is a social activist.

© 2025

© 2025