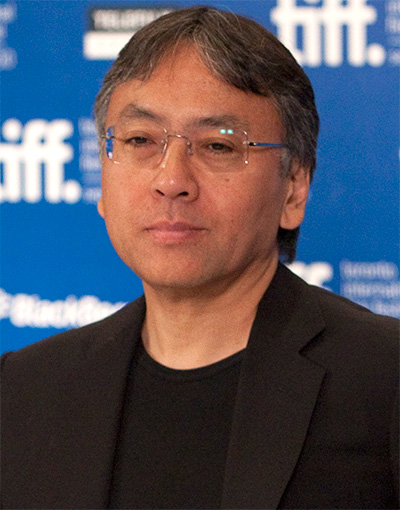

Celebrated novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, who has just won the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature, spoke to Arthur J Pais of Rediff.com in 2009, recalling his wonderful association with Sonny Mehta, editor-in-chief of Alfred A Knopf and chairman of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, who had just won a special award.

Nominated four times for the Man Booker Prize, Kazuo Ishiguro won a Booker in 1989 for his novel The Remains of the Day, later made into a

critically acclaimed film by producer Ismail Merchant and directed by James Ivory.

Born in Nagasaki, Japan, the 55 year old has lived in the United Kingdom since he was 5. His recent book Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall has received good praise.

His novel Never Let Me Go was featured on Time magazine’s 2005 list of the 100 greatest books in the English language.

He spoke to the late Arthur J Pais from his London home:

Sonny Mehta may not remember this, but he once told me a story about following his father-in-law across India during an election campaign. I had the impression it made quite an impact on him, and I think it has been a big influence on his various publishing strategies.

He had to accompany his father-in-law (the late Biju Patnaik, chief minister of India’s Orissa state for many years) on muddy paths to remote, difficult to reach places. It was important for his father-in-law to campaign not only in big cities but also in tiny villages. Sonny must have seen

then the link between small gestures and the big picture.

He felt it was important for writers to go on book tours in small cities as well as big ones, and for publishers and writers to be connected with booksellers and readers at the grassroots level.

When I’m touring, I’ve often had a bookseller, in a city thousands of miles from New York, talk about the time they discovered that the person who’d walked into their store to say hello was none other than Sonny Mehta, president of one of the nation’s great publishing houses. Booksellers are used to reading about publishing heads in trade magazines, but for most part someone of Sonny’s calibre doesn’t tend to make the effort to personally visit stores in person.

I should emphasise that this isn’t just good public relations. Sonny has a near-reverential attitude to a certain kind of bookseller of discerning taste, and I suspect he goes to pick up ideas and tips, as much as to establish a personal business link.

I have known Sonny for nearly three decades.

But long before I met him, when I was a student in 1970s Britain, I was reading the stylish paperbacks he’d launched under the Picador logo.

These books seemed to be very much for our generation, slightly counter-culturish, books like Michael Herr’s Dispatches. The designs were strikingly different from the books of that time, and what was inside felt cutting edge, alternative, quite highbrow. They were very important for my generation: In a way, as important as the music albums of that time.

I met him at a party in London shortly after I published my first novel.

I was 27 and unknown, but Sonny came up to me and talked to me with great respect and kindness, telling me he’d read my novel, how much he’d liked it and how he wished his company had published it.

I was very touched and encouraged by this.

Our professional relationship began with my third novel, The Remains of the Day, which he published in America in 1989, a year after he’d joined Knopf. He really threw himself behind that publication. I’d won some recognition in Britain by that point, but was still largely unknown in the States. I think Sonny made it something of a personal mission to make the book a success in America.

I stayed in his apartment for about a week during the publication, and he and Gita took me out to various places and introduced me to all kinds of people. Since then, whenever I’m on a tour of the States, he has insisted I stay with him during the New York stop. I know he regularly has his authors staying with him. In my experience, this is quite unique in a publisher.

On one occasion, Knopf put me up in a hotel in Manhattan, a very good hotel. But the stay lasted only a few hours. Sonny found out, turned up in the lobby, and checked me out. After that, I was his guest, and he and Gita looked after me morning till night.

I remember him telling me once, with genuine outrage, how when he was out of town, (novelist; Flaubert’s Parrot, Arthur & George) Julian Barnes had passed through, he had been put up in what Sonny called ‘a businessman’s hotel’. I’m sure this was some utterly luxurious place, but for Sonny, it wasn’t right for an author he respected.

He has a very special sense of how authors he admires should be treated.

During one of my stays, in the middle of an afternoon, he suddenly announced that the two of us were going for a walk. I thought it was going to be a leisurely affair, but instead we marched around Central Park at a frantic pace, not talking. I had real trouble keeping up with him even though I was then a young guy. I discovered later this was part of his fitness regime.

He works very, very hard. He’ll work late into the night, then get up early to read manuscripts before breakfast.

Once I had to get a ridiculously early flight out, and was sneaking around the apartment trying not to wake up Sonny and Gita. When I got to the kitchen -- this was around 5 am -- I found Sonny there, in his night clothes, reading a manuscript at the kitchen table. I gathered this was part of a regular routine.

I believe you can’t understand what makes Sonny tick without taking into account Gita, who has one of the liveliest intellects I’ve ever come across. They spend a lot of their time testing out ideas on each other -- about politics, literature, social trends, movies, anything.

Their scope is very international, and when they’re at home, you’ll hear them arguing, sometimes quite heatedly, with the unselfconsciousness of people thinking aloud to themselves and each other. They know one another very, very well, and Sonny tends to be at his most relaxed when Gita is present. I think she is by far the biggest influence on Sonny, the way he thinks, the way he behaves, what he thinks is important.

Sonny is devoted to his writers and worries a lot about them. He might seem distant during a meal, and then he’d reveal that he’s worried about how a particular writer of his would react to the bad reviews her latest novel was getting. What impact would this have on the book she’s currently writing? Would it discourage her from continuing with her career?

Quite often, he worries about writers he doesn’t even publish.

He once confided to me how excited he gets when he overhears people, at a party or in a restaurant, discussing with enthusiasm a Knopf book. A real twinkle came into his eyes even as he was telling me this. He told me he’s seized by the urge to interrupt and say: ‘Excuse me, but I

just wanted to say, I published that book. And I’m so proud and pleased you like it.’ I got the impression he’s never actually done this, but this told me a lot about why Sonny Mehta is in publishing.

He has a wry sense of humor, which sometimes stretches to the blackly comic. About ten years he had a serious health problem; he underwent bypass surgery. I spoke to him by phone while he was still in the hospital, and when he related the whole story of his emergency treatment and operation, everything he said was screamingly funny. There was a very darkly funny part about how after surgery a number of patients are led into a room to be lectured about exercising during convalescence. And in the middle of one exercise session, one patient started to have another seizure.

I’ve heard people talk about him as mysterious, even hidden.

But I’ve always found he’s very open in talking about what makes him happy and what brings him down. He knows how to laugh at himself, and the strange things we all do to keep going.