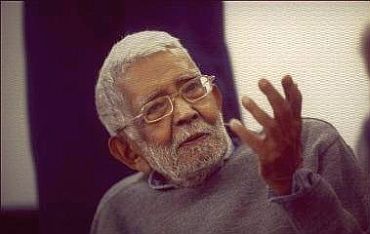

Noted political scientist Rajni Kothari passed into the ages on Monday.

Noted political scientist Rajni Kothari passed into the ages on Monday.

Renowned as a scholar and an activist for his continuing search on intellectual, political and ethical dimensions of contemporary reality, Rajni had reflected on India's past and future, for rediff.com as part of a series commemorating the nation's fifty years of freedom.

We reproduce the 1997 feature below:

As we enter the last few years of this century and move into the next millennium, the country seems to be in the throes of a series of changes in both the structure and culture of political power, the ground for which had already been laid before the end of the half century of independent nationhood.

These 50 years encompass both a blossoming of the democratic enterprise that the country had set its heart on and its gradual erosion and dissipation.

Historical change, however, cannot be described as a mere sequence of ups and downs. Despite the steady erosion of both institutions and the values that were cherished in the early decades after Independence, much of what had started then is still part of our national consciousness.

The peculiar bland of creative nationalism and persisting pluralism of indigenous society that had produced India's democratic culture is still with us. It is still woven into whatever remains of the institutional fabric of the polity.

These characteristics will continue to inform the emerging future of democracy in India, even though the key actors and their social bases as well as ideological moorings will change in some basic ways.

The problem with the first 50 years after Independence was that while it should have been clear from the beginning that democracy entailed a political process where the majority of the people should be deciding the course of events, as also that notions of justice and equity were inherent in the democratic idea and therefore there was a necessary and compelling socio-economic logic to it, the leadership (including Nehru and other 'founding fathers') had failed to build into the scheme of things an egalitarian ideology and a corresponding set of policies and programmes.

This led to a situation in which a small minority of people continue to dominate the working of the polity and, over time, the politics of manipulation and willful deceit got the better of the politics of fulfilling the inherent logic of democracy.

This having been the case, both the failure to live up to the expectations of the people from the system, and the gradual erosion and eventual undermining of the institutional fabric through which these expectations were to be realised became inevitable.

Failure to build into the democratic edifice a set of ideological contours necessarily resulted in steady decline and growing redundancy of the democratic spirit.

There were still a large number of individuals, both within the confines of the system and pressing on it from outside, who were keen to preserve the values of justice, equity and democracy as spelt out in considerable detail in the Directive Principles of State Policy of the Constitution. But in the end they proved powerless (including those who happened to be 'in power' whether in governments, in the running of the economy, in diplomacy, in business or in the voluntary sector) and failed to produce results.

Inevitably, they got increasingly driven to merely making rhetorical noises.

Meanwhile, the 'system' itself was found to go back on its commitments of removing poverty, unemployment, social exclusion and growing atrocities on vulnerable sections, especially women and children. Indeed, there developed in the elite a peculiar amnesia on these issues.

Meanwhile, thanks to the widening gap between the small minority that operated the system and the large majority that was left out of it, there grew a generation of middle and lower middle class youth that could not care less about basic values, and which was instead almost wholly consumed by the new economic logic of money, the yuppie culture of consumerism and a free for all.

And of course, reinforcing all these pathologies affecting the democratic enterprise has been the mass media and advertising agencies, the most subtle manipulation of all ideas and institutions coming from the very bearers of 'freedom of expression,' both the electronic and the print media.

And yet, there is already emerging a whole variety of counterforces to this degenerate and derailed system, based on the very premises and assumptions of the democratic polity.

Tired and demoralised by the continuous slide-down of the system and its institutions and operators, no longer willing to leave things to existing parties and agencies of governance, there has been under way, for some time now but particularly reflected in the 1996 election, an emergent new politics of mass aspirations and assertions, in effect rejecting the system as it operated, especially the political parties and the party system as also the long held preoccupations with 'national' goals, issues and slogans.

Six major parameters of this shift to a new set of actors insisting on their rights as laid out in the very concept of democracy, and seeking a new political order that could uphold these rights can be identified.

First, there has taken place a considerable awakening, mobilsation and political and ideological assertions of what can be called the 'Dalit' movement in politics.

The concept of Dalit being conceived as a broad, encompassing, set of castes and classes, producing a new form of radicalism than has been represented by either the Liberal or the Marxist or the 'new social movements' perspectives, most of which were found to lack of social agenda and failed to concede to the Dalits their rightful claims, and a clearly defined role in running the affairs of the state through direct access to political power.

Second, there has taken place a large-scale politicisation of caste groups and minority communities at the lower reaches of the social hierarchy, resulting in a challenge to existing structures and hegemonies despite efforts (which are inevitable) at sowing seeds of discord among them by existing parties and governing structures.

Third, thanks to a series of progressive legislative enactments, a large variety of hitherto disempowered social strata have been empowered through reservations and other forms of affirmative action (building further upon the rights assigned to the SCs and STs through acceptance of the report the Mandal Commission by the National Front government) which have now been accepted, at least in principle, by all parties and governments at different levels and which, in consequence, has put quite a number of individuals from these strata into positions of power.

Fourth, 1996 saw a major electoral backlash against a discredited political elite (both leaders and parties) and derailed system of governance. The result was that no single party returned to power (in the sense of enjoying a majority in Parliament) and with the voters' preference for local issues, the system was forced to structure the process of governance around a coalition of small and regional parties which, incidentally, happens to be a coalition mostly composed of middle and lower castes in the social hierarchy.

Fifth, this necessity forced the acceptance of a far more federal system of governance (both regionally and socially speaking), than was ever achieved by the proponents of states' rights earlier on (including by a cabal of state level chief ministers in the early and mid-eighties).

And sixth, and perhaps more basic than anything else, there has taken place an unprecedented coming together of secular forces, at both mass and institutional levels, for the first time putting on the defensive communal and fundamentalist forces.

The combination of these six factors, each one of them building on the idea of democracy which had been promised at the very dawn of independence, but had been sidelined due to the hijacking of the whole democratic apparatus by a small minority of politicians and bureaucrats in league with entrenched interests in rural, urban, professional and international arenas can lead to the beginnings of a transition -- transformation -- to a new system of governance.

The political process unleashed by this new awakening, will, of course, be subjected to a lot of backlash from those who have enjoyed power and privilege for close to half a century.

Also, the new bearers of power from the deprived sections will not necessarily pursue the interests of the large masses in whose name they are likely to assume power (as some of them already have). There is still a long way to go as far as the masses are concerned. They will continue to have to press upon the merging new coalitions that come to power following 1996 and other succeeding elections.

In reality, they will have to get engaged in transforming the very process of governance and the nature of the State.

In large parts of the world governments are found to pursue policies that prove inimical to the well being of large sections of the people.

This includes governments that claim to represent - and some of them do represent - deprived social strata, progressive ideologies and sets of policies that were designed (at least to begin with) to benefit the poor and the oppressed.

There are always limits to what governments can do.

The modern State is a complex of promises and betrayals. There is never a respite in politics, never a point of final arrival.

Of all the things that India has inherited and imbibed, in both theory and praxis, democracy stands out as having the most cutting edge, at any rate for the poor and exploited mass of the people.

As the torch of democracy passes down the social terrain, it must make things better. But it will still be an uphill task.