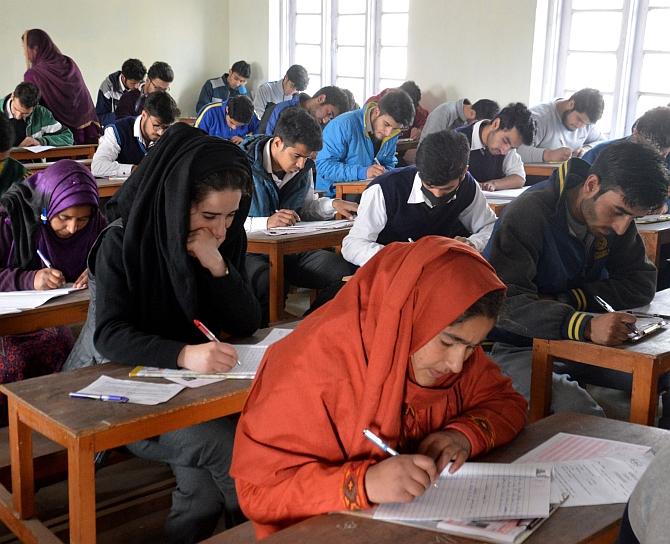

The ongoing violence in the valley is driving students to excel, but it is also making them angry, discovers Ritwik Sharma.

"I am used to my father being in jail," says Sama Shabir, a separatist leader's daughter who topped the recent CBSE Class XII exams in Jammu and Kashmir.

The humanities student grew up accustomed to visiting her father Shabir Shah in various prisons across the state.

But when the founder and president of the Jammu and Kashmir Democratic Freedom Party was locked up in New Delhi's Tihar jail last year, it was traumatic for Sama, her mother and younger sister.

"In Tihar, he is being kept like a criminal, although he is a political prisoner. It was very disturbing to know that he wasn't given medicines or proper food. But I thought I should not take it as a negative and do something to make him proud. With hard work and dedication, you can cope with any situation, however hard," says Sama, who scored 97.8 per cent.

The 64-year-old Shah, who was declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International, has spent over 31 years in jail and is known among supporters as the 'Nelson Mandela of Kashmir.'

Sama draws inspiration from him, as she prepares to study law.

In the past decade, ruthless State repression and civilian uprisings have drawn a new generation of youths to lead the resistance.

In July 2016, the killing of young Hizbul Mujahideen 'commander' Burhan Wani sparked furious unrest across Kashmir which was met with a controversial use of pellet guns by the police and paramilitary forces to quell protesters.

Scores of civilians were blinded by the 'non-lethal' ammunition.

Insha Mushtaq, a girl from a remote village in the Shopian district of the state, became the face of pellet victims.

On July 11, 2016, she had opened a window at her home to peek at the protests outside.

The next moment her face was riddled with hundreds of pellets fired by policemen.

She was first taken to a nearby facility.

The doctors referred her to Srinagar, where she was in a coma for 12 days.

Later, she underwent multiple surgeries at AIIMS in Delhi and in Mumbai.

Last year, she studied at home and this January she passed her Class X state board exams, which follows the NCERT curriculum.

Her achievement was celebrated across the valley.

She is now learning computers, Braille and English at the Delhi Public School in Srinagar.

Science was her favourite subject and she wished to study medicine, but after losing vision, she has chosen to pursue humanities.

Even though she regrets having to suddenly depend on others to go about her daily life, at home and outside, she is learning to adjust to her new life.

One of the things she loves doing these days is playing cricket at her new school.

"Aage jaake mera sapna hai Malala banna, bas (My dream is to be like Malala)," she says, referring to the Nobel Laureate from Pakistan who survived a gunshot wound in the head after an assassination attempt by the Taliban and went on to become a noted activist for education of girls.

According to Javid Ahmed Bhat, general secretary, National Association for the Blind, Jammu and Kashmir branch, the overall figures of those injured or blinded by pellet guns could be anywhere between 1,100 and 1,600.

After a survey last year, the voluntary organisation had identified over 100 persons who had lost vision completely.

Among them, 25 to 30 were of school-going age, he says.

The NGO trains volunteers to teach blind children at their homes or nearby schools.

It is supporting 10 such children, including Insha until last year.

Bhat says in the past decade schools have remained shut for long periods due to the ongoing violence.

Besides poor attendance, children are also suffering more than earlier because they have become direct targets.

Among the examinees who made news in January was Ghalib Guru, the son of Afzal Guru, the 2001 Parliament attack accused who was hanged five years ago.

Ghalib passed the higher secondary school exam conducted by the state board with distinction.

He is taking tutorial classes in Srinagar to prepare for the medical entrance exams.

His mother Tabassum, who stays at their home in Baramulla, says like everyone else, Ghalib had to mostly study at home after the unrest in 2016.

She was advised by a relative that Ghalib could apply for scholarships to study medicine in Turkey.

But the family has been denied passports, which she had applied for to be able to perform Hajj.

"I had applied for passport in 2015, but so far nothing has happened and the case is stuck in courts. What choice do we have then?" asks Tabassum, who has petitioned the high court.

A familiar refrain is the growing anger against state policies and the lack of fear among the young.

Sama says the youth are more aware and educated today and therefore less willing to ignore continuing injustice.

"I have many friends in India, who are like family. No one is my enemy. Kashmiris don't have problems with the people, but the policies of the government," she adds.

Parents express helplessness, even as they view provocations from the state as fuelling anger among youth.

Tabassum points to the incident of a 21-year-old protester being run over by a CRPF vehicle in Srinagar a week earlier.

"Why do you need to kill protesters? Why not beat them up or even jail them instead? Killings only spark off more anger and resistance."

Sama's mother Bilqees Shah, a medical superintendent, says, "What I am more worried about is that people -- be it youth, militants or the elderly -- earlier used to rush away from an encounter, today it is the opposite."

"For the youth of today, it doesn't even matter if they get killed. What is pushing them towards it? That has to be addressed."

Writer and policy analyst Radha Kumar, who was one of the three government-appointed interlocutors for Jammu and Kashmir in 2010, says school children have been caught in the cross-hairs for decades, and that on an average the valley has lost almost a third of school days per annum over the past 15 years.

Children from poorer families are the worst affected because few of them can catch up on studies at home, and their dropout rate is also high, she adds.

According to the local media, the latest economic survey report tabled by the state government in the legislative assembly showed a significant increase in dropouts.

The dropout rates in primary (age-group of 6 to 10) and upper primary (11 and 12) classes grew from 6.93 per cent and 5.36 per cent in 2015-2016 to 10.30 per cent and 10.20 per cent in 2016-2017.

When asked about administrative failure to secure school environment, Kumar says prior to shutdown calls militants largely left educational institutions unharmed, but the burning of schools a couple of years ago suggested a further dark turn in the insurgency.

"Certainly, the government could do more, for example, by talking to the JRL (Joint Resistance Leadership, an alliance of separatist leaders) to declare that schools and education centres should be treated as protected zones that are not affected," she says, adding that the JRL needs to specify exemptions from shutdowns, such as schools and colleges, and governments need to build a peace process.

Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025