'We all know nations that can be identified by the flight of writers from their shores.

'These are regimes whose fear of unmonitored writing is justified because truth is trouble.

'It is trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the political hack, the corrupt justice system and for a comatose public.'

The legendary Toni Morrison passed into the ages on August 5.

A powerful voice in the literary world, the 88-year-old, who impacted millions across the world with her words. she was the first African-American woman to be awarded with the Nobel prize for Literature.

In 2002, she was honoured with the Presidential Medal for Freedom by President Barack Obama.

Morrison's words hold a mirror to Life.

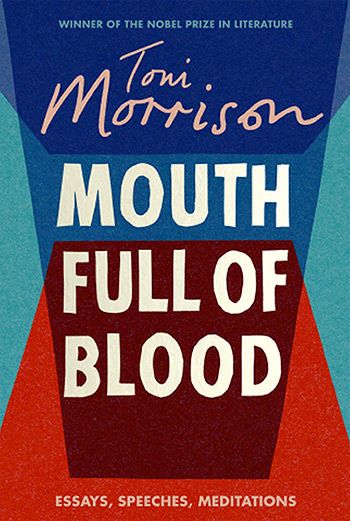

This excerpt, from her recently released Mouth Full Of Blood (February 19, 2019), reflects what is happening in many countries across the world today.

Authoritarian regimes, dictators, despots are often, but not always, fools.

But none is foolish enough to give perceptive, dissident writers free range to publish their judgments or follow their creative instincts.

They know they do so at their own peril.

They are not stupid enough to abandon control (overt or insidious) over media.

Their methods include surveillance, censorship, arrest, even slaughter of those writers informing and disturbing the public.

Writers who are unsettling, calling into question, taking another, deeper look.

Writers -- journalists, essayists, bloggers, poets, playwrights -- can disturb the social oppression that functions like a coma on the population, a coma despots call peace, and they stanch the blood flow of war that hawks and profiteers thrill to.

That is their peril.

Ours is of another sort.

How bleak, unliveable, insufferable existence becomes when we are deprived of artwork.

That the life and work of writers facing peril must be protected is urgent, but along with that urgency we should remind ourselves that their absence, the choking off of a writer’s work, its cruel amputation, is of equal peril to us.

The rescue we extend to them is a generosity to ourselves.

We all know nations that can be identified by the flight of writers from their shores.

These are regimes whose fear of unmonitored writing is justified because truth is trouble.

It is trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the political hack, the corrupt justice system and for a comatose public.

Unpersecuted, unjailed, unharassed writers are trouble for the ignorant bully, the sly racist and the predators feeding off the world’s resources.

The alarm, the disquiet, writers raise is instructive because it is open and vulnerable, because, if unpoliced, it is threatening.

Therefore the historical suppression of writers is the earliest harbinger of the steady peeling away of additional rights and liberties that will follow.

The history of persecuted writers is as long as the history of literature itself. And the efforts to censor, starve, regulate and annihilate us are clear signs that something important has taken place.

Cultural and political forces can sweep clean all but the “safe,” all but state- approved art.

I have been told that there are two human responses to the perception of chaos: naming and violence.

When the chaos is simply the unknown, the naming can be accomplished effortlessly -- a new species, star, formula, equation, prognosis.

There is also mapping, charting or devising proper nouns for unnamed or stripped-of-names geography, landscape or population.

When chaos resists, either by reforming itself or by rebelling against imposed order, violence is understood to be the most frequent response and the most rational when confronting the unknown, the catastrophic, the wild, wanton, or incorrigible.

Rational responses may be censure; incarceration in holding camps, prisons; or death, singly or in war.

There is, however, a third response to chaos, which I have not heard about, which is stillness.

There is, however, a third response to chaos, which I have not heard about, which is stillness.

Such stillness can be passivity and dumbfoundedness; it can be paralytic fear. But it can also be art.

Those writers plying their craft near to or far from the throne of raw power, of military power, of empire building and countinghouses, writers who construct meaning in the face of chaos must be nurtured, protected. And it is right that such protection be initiated by other writers.

And it is imperative not only to save the besieged writers but to save ourselves.

The thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being posed, unstaged plays, cancelled films -- that thought is a nightmare. As though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.

Certain kinds of trauma visited on peoples are so deep, so cruel, that unlike money, unlike vengeance, even unlike justice, or rights, or the goodwill of others, only writers can translate such trauma and turn sorrow into meaning, sharpening the moral imagination.

A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity.

Excerpted from Mouth Full Of Blood by Toni Morrison, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

© 2025

© 2025