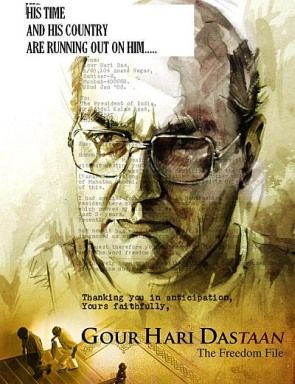

It took Gour Hari Das three decades to wrangle out a certificate recognising his work as a freedom fighter. His struggle is now the subject of a film In the dead of night during the mid-1940s, Gour Hari Das would customarily set out of his house and sprint alongside passing trains, relying on their beacons to guide his 14-year-old feet.

In the dead of night during the mid-1940s, Gour Hari Das would customarily set out of his house and sprint alongside passing trains, relying on their beacons to guide his 14-year-old feet.

He was joined in this exercise by others roughly his age, all part of a group called the vanar sena that nimbly ferried covert messages and publications of the freedom movement.

Many years later, the same pair of legs tirelessly carried him up and down the stairs of government offices in Mumbai. The communication he sought this time was a certificate recognising his work as a freedom fighter - it took three full decades to arrive.

The prolonged personal tryst for acknowledgment got him more attention than even his participation in the freedom struggle. His travails form the subject of an upcoming film Gour Hari Dastaan - The Freedom File.

After reading a newspaper report, director Ananth Mahadevan was struck by the irony in Das' experience.

"Here was a man fighting for identity in a country that he helped to free," he observes. Mahadevan traced Das to his current home in suburban Mumbai and convinced him to share his story. The film, with screenplay by journalist and poet C P Surendran, has been shortlisted for screenings at three Indian film festivals so far.

In his first meeting, Surendran says he did not find Das terribly impressive but noted an understated grit about him. Mahadevan too was nonplussed during an initial interaction.

"Leave alone three decades, this man did not look like he could have fought for three days."

His largely self-effacing persona led the film's makers to play on silences.

Das' extraordinary determination seems to stem from a desire to hold on to remarkable bits of an otherwise routine life.

"He has no interests outside his small life, no theatre, no art," says Surendran. "What happens then is your identity becomes more and more crowded around one or two events. You take that away and there is nothing left."

Das ushers in guests at his modest house in faraway Dahisar with a slow but unwavering gait.

His neatly tailored shirt, pants and enduring wreath of hair are all white.

A ball point pen and mobile phone share space in his breast pocket.

His hearing is weak, he warns before settling into a brightly-upholstered rocking chair for the interview.

On one wall are photos of goddess Durga and of his father, Hari Das, also a freedom fighter who encouraged him to join in the movement.

Another wall is furnished with a small clock and a calendar from Vijaya Bank fluttering gently under the fan.

Toppling expectations of short replies, the 84-year-old describes his story in fair detail.

In the border village of Jhadpipal in Odisha, Das volunteered in independence-related activities for five years.

At the time, colonial rule was at its fag end and the British grip on India was somewhat weakened.

It was a period of blithe political involvement.

He remembers equally being stirred by the speeches of emerging Indian leaders, and teasing or laughing with peers of the vanar sena.

After hoisting the Indian flag against orders on Independence Day (celebrated on January 26 during British rule), he was sentenced to nearly two months in jail in 1945.

Das was the second of nine sons and four daughters.

He met Lakshmi, who lived two villages away, on his father's suggestion.

The senior Das asked his son to seek her help in preparing voter lists for the first election after Independence.

Eventually, the two would marry and have two sons. Lakshmi is reticent, conversing mostly with her husband in rapid Odia. She has a habit of clutching a handkerchief tightly in her first, a trait actress Konkana Sen Sharma picked up while preparing to portray her.

Das, who studied under Gandhiji's nayee taleem or 'education through craft' programme, worked for the Khadi and Village Industries Commission throughout his professional career. He was called by the commission to help develop weaving technology in Maharashtra.

During a move to create records of freedom fighters in Odisha, Das had applied for identification but the endeavour never took off.

After moving to Mumbai, he revived efforts for recognition because it would have helped his elder son get an engineering seat at the Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute.

Of course, the request was not processed in time and his son later won admission to Indian Institute of Technology Bombay on merit.

Still, Das persisted, travelling in turns to the collector's office and Mantralaya.

The procedure was slowed by a decision of the then Maharashtra government to not support freedom fighters from outside the state.

Das had to gather proof that he was not drawing benefits in Odisha and that he had spent more than one month in jail during the struggle. He found support in his neighbour Rajeev Singhal and activist Mohan Krishnan of NGO National Anti-Corruption and Crime Preventive Council.

His first letter requesting acknowledgment was dated 1976 and the certificate finally came through in 2009.

Elements of fiction have been introduced in his cinematic character, which unlike Das, faces the onset of Alzheimer's disease.

Vinay Pathak, who plays the freedom fighter in the film, lost weight and focused on mastering Das' pauses and silences.

Mahadevan and Surendran also found it worthwhile scripting the pitfalls of the bureaucracy, with government offices constantly demanding an additional document, moving files slowly or even misplacing them.

As Surendran puts it, Das' story reflects the "inhumanity of people who actually are in a position to help, the lack of right to services and the very exacting art of sweating the small stuff that India has made a specialty out of".

Das admittedly has trouble remembering specifics or finding the correct term to describe something.

He narrates his experiences, often jumping back and forth between years and places.

He maintains physical records too, which, much like his memories, are exhaustive but stored in random order.

Das disappears into the bedroom for several minutes in search of his freedom fighter certificate and emerges with a box file and a plastic bag packed with documents.

Inside the portfolio are yellowing letters, receipts and newspaper clippings, reinforced with glue and blank sheets.

"I get yelled at for this. I keep a lot of kachra (trash)," he confesses sheepishly.

Mahadevan says Das would relate a new anecdote every time he met him, including one which he worked into the script much after it had been bound.

"Das talked of having a full head of hair in his youth and how right after one woman praised him for it, he began balding. It was the kind of moment that my film needed and showed a romantic side to Das that we did not know existed."

Indeed, Das' sense of humour is present, though not readily visible. While posing for photographs, he observes wryly, "All the smiles have gone out of my face."

The textile veteran insists he was never interested in the pension (he was already getting from the Khadi Commission), saying the struggle for freedom was selfless.

At 84 years, he is now general secretary of NACCPC. The much sought-after certificate, when it was ultimately awarded, was a bittersweet victory.

Instead of an engraved copper plaque issued for such honours, he received a statement on paper.

In a rare moment of anger, the patient Das remembers asking Mantralaya officials, "Is the government so strapped for money now?"

.jpg)

© 2025

© 2025