Indian anti-slavery crusader Kailash Satyarthi will receive the Nobel Prize for Peace in Oslo today, December 10.

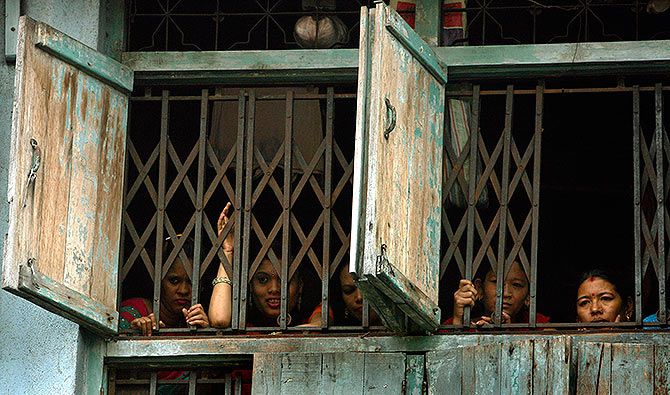

A Ganesh Nadar/Rediff.com visits the infamous cages of Mumbai's oldest red light district, Kamathipura, to find out how human trafficking has given India the awful reputation of the nation with the highest slavery rates in the world.

All photographs published only for representational purposes.

Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

The blood red lipstick is a signal. All the waiting women sport them. As your eyes meet, they smile invitingly, indicating they are available.

She was on the heavier side. Opposite her sat a thinner girl. Both were smiling. Both had dead eyes. Both had been hardened by a horrifying trade that does not respect men or women.

"You have come so early," said the stouter one. "Come here. Though she wasn't the one I was looking for, I walked towards her.

Then, I saw her. The one I was looking for. She was walking out of a building. She was very thin -- and very young.

"You," I called out. "Come here."

There was no greeting. No small talk.

"Rs 500," she said bluntly. "Will you pay?"

I nodded.

"Okay. Come with me."

This is Kamathipura, Mumbai's infamous red light district.

The girls can be seen in cages along the roadside. They wear bright lipstick, short skirts and tight blouses with plunging necklines.

There is no romance here, only sex which is bought and sold with a nod.

Once, the cages sprawled across 14 streets in the area. Over the years, the sex trade in Kamathipura has shrunk to a fraction of what it once was.

But everything else remains the same. That hasn't changed in the last century.

Many of the women and children plying the flesh trade have been sold into the profession by relatives, or by people they have trusted.

Organised gangs lure unsuspecting women and children to the cities under the pretext of employment or education and sell them to brothel owners.

Everyone knows this happens, but no one raises a voice because these children and women come from a province of Indian society which few care about.

Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

The thin young girl leads me back into the building she has just left.

"My first customer of the day," screams the angry woman I left behind. "You robbed him, you b***h!"

"Ignore her," advises the thin one. She is already running up the staircase.

I can only see the way until the first floor. After that, it is pitch dark. Outside, the sun shines brightly in the afternoon sky.

"Walk up," she shouts. "I am here."

There are girls all over the place. Most of them look sleepy.

"You wait here," she tells me and runs off to get a key.

We enter a tiny room. It has a bed and barely two feet of standing room. There is a tubelight near the ceiling and a tiny wall mounted fan that does not have a protective cover. I would have to make sure I did not raise my hand.

"Pay me," she demands.

I pull out Rs 500 from my wallet.

"And Rs 20 for the bed," she adds firmly.

I do not have change so I hand her an additional Rs 50. It is sad to see how the extra tenners make her happy.

"Come on, take off your clothes," she says as she starts to remove her own.

"I don't want to undress. I wanted to see you," I say.

"Okay," she shrugs. "See." She strips quickly, with practised ease.

"Please dress up," I tell her. "I meant I just want to talk to you."

She comes from a poor family. Her mother tongue is Bengali. She has studied up to Class 4.

"I was married when I was 15. We stayed in Delhi. About a year after we were married, my husband told me to get ready. He said we were going for dinner to a friend's house."

Her voice remains expressionless.

"There were many girls in that building. He took me to a room where a man and a woman were waiting."

Her husband said he had forgotten to buy sweets and it was bad manners to go to someone's house empty handed.

"He told me to wait. He said he would buy the sweets and return quickly."

He never came back. She tried calling him, but his phone was switched off.

"The lady asked me for my mobile phone and never returned it," she says.

When she tried to leave, they stopped her.

"They said my husband had sold me to them and I could not leave for two years."

"I told the lady I was two months pregnant, but that did not seem to bother her."

There were 15 other girls there, she says, but none as young as she was.

"The girls warned that I would be beaten up badly if I tried to run. They also said that, if I resisted, the customers would pay more to beat me up and rape me. The brothel owner liked girls who resisted as they brought in more money."

"I did not resist," she says quietly.

"As I was the youngest I got the maximum customers on any day. As my pregnancy advanced, one of the girls taught me about oral sex."

And so, she continued working.

Photograph: Vivek Prakash/Reuters

Her child was delivered by the woman who ran the brothel. The 'madam' gave her Rs 10,000 and told her to leave.

"The madam told me, 'You were sold for two years, but you have paid back in eight months'."

She went back to her village. "I told everyone that my husband was in Mumbai. Only my mother knew he had deserted me. My mother checked in his village, but my husband had not come back."

In Delhi, she had heard the girls talk about Kamathipura in Mumbai. "They used to say every girl got work there. No one was ever turned away."

She told her mother she had friends in Mumbai and left when her child was nine months old.

"I did not tell her about what I did," she says.

She was young and was accepted at the first brothel she entered in Kamathipura. But why did she return?

"I come from a very poor family. I didn't want to burden my mother."

She was just 18 years old then. "My madam told me to say 20 if anyone asked," she says.

Today, she is 21. And she sees no way out of the flesh trade.

"My daughter is sick," she says. "I have borrowed Rs 30,000 from Anna (a money lender). He charges 25 per cent interest. I have to pay him back in six months."

She has to give a part of what she earns to the brothel owner. If a pimp brings a customer, he takes his share as well. "And we have to pay for the use of this room by the hour," she says.

Life, though, she says, is not too bad. "What other work will a girl who has passed Class 4 get? I am happy here."

After six months, when she has repaid her loan, she plans to return home. "There is this boy who wants to marry me," she smiles.

"Old man, you finished so fast," says the other girl loudly. The other girls laugh.

I look at the girl, whose story I had just heard.

Despite the horrors that life has handed her, her eyes has not lost their innocence.

The tragedy is that this is not just her story. It is the story of millions of girls in India, who are sold against their will into the flesh trade.

Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

India leads the world in slavery and in the trafficking of women. Areas like Kamathipura in Mumbai, Sonagachi in Kolkata and G B Road in Delhi continue to exist.

The late 1990s that saw the rise of AIDS marked the beginning of a change in Mumbai's oldest red-light district. Tough police crackdowns made soliciting difficult.

The number of sex workers began to dwindle.

The government's redevelopment policy offered sex workers an opportunity to move out of the profession and subsequently out of Kamathipura. Land developers began taking over the real estate.

In 1992, the Bombay Municipal Corporation recorded 50,000 sex workers in Kamathipura. By 2009, there were only 1,600 sex workers; many had migrated to other areas in Maharashtra.

Senior Police Inspector Nandkumar Krishnarao Mhetar heads the Nagpada police station; Kamathipura falls under its jurisdiction. It is one of the most difficult areas to police in Mumbai, due to the presence of various ganglords who deal in prostitution, gambling and drugs.

"We conduct raids when we get information that new girls have come in. We always go with a NGO (non governmental organisation). The girls open up more easily to the NGOs. We ask them if they have come here of their own free will or if they have been forced or cheated," says Mhetar.

Depending on their answer, the police take them into custody. "We also arrest those who brought the girls here and those who are doing business with them."

But that applies only to adults, he says. "When we find a child, she is rescued irrespective of whether she came here on her own or was trafficked. All those who are using her are put behind bars immediately."

All cases are registered under the Prevention of Immoral Trafficking Act. "We can also chargesheet them for carrying on an illegal business," he says.

The rescued women are handed over to the court, which keeps them in protective custody in government and non-governmental organisations in the city. They can return to their homes with the court's permission.

But the profession takes its toll; most of the women don't go back.

"Earlier," says Mhetar, "there would be a lot of publicity when girls were rescued. Now that there are very few of them here, the media has forgotten this place."

Statistics obtained from the Mumbai police reveal that, in 2012, 119 women were rescued from Kamathipura. Sixty-four accused -- including nine male and five women brothel owners; 38 male pimps and two female pimps and 10 operators (operators manage the day-to-day business for the brothel owners) -- were chargesheeted under the Prevention of Immoral Trafficking of Women Act.

In the first six months of 2013, 31 women were rescued in four separate raids. Four brothel owners, two managers, six women and a pimp were put behind bars.

This year, the police stations at V P Road, D B Marg and Nagpada have conducted 23 raids and rescued 116 women and four young girls.

Eighteen women brothel owners, five male brothel owners, eight women pimps, five male pimps and thirty-three operators have been arrested.

Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

Preethi Patkar runs the Prerna Sanstha, which has been working in Kamathipura for almost two decades.

"Once the girls are rescued, their age is verified medically," says Patkar. "The children are sent to separate homes under the Child Welfare Committee."

The CWC is the sole authority when it comes to matters concerning children in need of care and protection, says the Delhi police Web site. A CWC has to be constituted for each district or group of districts, and consists of a chairperson and four other persons at least one of whom should be a woman.

Patkar says it is important to ensure that children are released into the custody of their legal guardians only if the latter are capable of looking after them.

"If they are financially weak, there is a good chance that the child will be sold again," she says. "In that case, we object and tell the magistrate that the child should not be released from the home."

Patkar's NGO teaches the children to work at petrol pumps and beauty parlours. They are also taught fashion designing. "The idea is to rehabilitate them properly instead of teaching them candle making and chalk making, as was done earlier," she says.

If you visit Kamathipura today, you will find doctors, beauticians, dentists, traders and money lenders running their businesses here.

Much of Kamathipura has been converted into a tailoring hub where readymade garments are made in minimum space. Cutters, tailors and washers work in horrifyingly cramped quarters to turn out cheap garments for the poor.

Low wages, long working hours, non-existent holidays and cramped living quarters ensure they are no better than the prostitutes who once plied their trade here.

All photographs published only for representational purposes.

© 2025

© 2025