Some 1,100 years ago, Uthiramerur had an election system similar to what India has today.

T E Narasimhan reports.

Tucked away in the Kanchipuram district of Tamil Nadu, 90 km from Chennai, is the small temple town of Uthiramerur.

It is located along national highway 45, running south-west of Chennai. A tight right straightens out on to the road that leads to this busy small-town market.

The 25-km road runs in the middle of the dry agriculture land on both sides slightly dotted by industrial establishments and education institutions

There are three famous temples in Uthiramerur -- The Sundara Varadaraja Perumal temple, dedicated to Vishnu; the Subramanya temple, for Muruga, and the Kailasanatha temple, for Shiva.

Besides, Uthiramerur has another rich institution it prays to, and that is 'democracy'.

Some 1,100 years ago, this town had an election system similar to what India has today -- including references to how elected members must be subjected to the right of recall.

Around the Sundara Varadaraja Perumal temple there are about ten traditional houses. 82-year old Srinivasan lives here, as does Sridhar.

Their families have lived in Uthiramerur for many decades now, and they have many stories to tell.

The Paranthaka Cholas ruled this area and introduced systems of governance that were the precursors of today's governance.

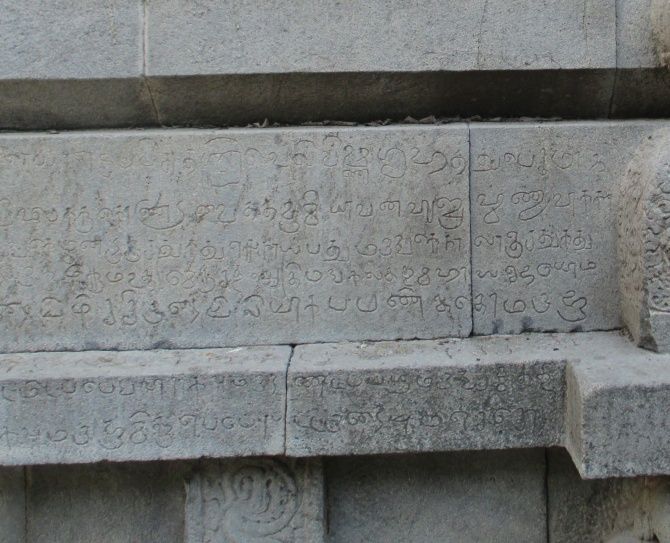

There is also evidence of a perfect electoral system and a written constitution prescribing the mode of elections in the forms of inscriptions on the walls of the village assembly hall (grama sabha mandapa), which is a rectangular structure made of granite slabs.

"This inscription, dated to 920 AD during the reign of Parantaka Chola is an outstanding document in the history of India," says a representative from the Archaeological Survey of India at the site.

The inscription gives astonishing details about the constitution of wards, the qualification of candidates contesting elections, the disqualification norms, the mode of elections, the constitution of committees with elected members, the functions of the committees and the power to remove the wrong-doers.

"On the walls of the mandapa are inscribed a variety of secular transactions of the village, dealing with administrative, judicial, commercial, agricultural, transportation and irrigation regulations, as administered by the then village assembly, giving a vivid picture of the efficient administration of the village society in the bygone era," the ASI official says.

As per the inscriptions, a huge mud pot (kudam) was placed at a central location of the town or village, which served as the ballot box.

The voters wrote the name of their desired candidate on the palm leaf (panai olai) and dropped it in the pot.

The leaves were taken out from the pot and counted. Whoever got the highest number of votes was selected the member of the village assembly, notes Ganesan, a former MLA.

The entire village, including the infants, had to be present at the village assembly mandapa at Uthiramerur when the elections were held. Only the sick and those who had gone on a pilgrimage were exempt.

According to the inscriptions, the village was divided into 30 families, and one representative was elected for each family.

Specific qualifications were prescribed for those who wanted to contest. The essential criteria were age limit, possession of immovable property and minimum educational qualification.

Only those who owned land, that attracted tax, could contest. Another interesting stipulation was that such owners should have a house built on a legally-owned site.

A person serving in any of the committees could not contest again for the three terms, each term lasting a year.

Elected members, who suffered disqualification, were those who accepted bribes, misappropriated others' property, committed incest or acted against public interest.

If one was proved corrupt during his tenure, he, his family members and even his blood relatives could not contest elections for the next seven generations.

A 10th century record, which was in the form of inscriptions at this site also reveals how the fines imposed on the wrong-doers of the village were administered.

Those who were fined for wrong deeds were called 'dhushtargal' (criminal).

The fines were imposed on them by the village assembly and the sitting elected members.

The fines imposed were to be collected from the 'dhushtargal' and settled by the village administrators through the assembly within the same financial year, failing which the assembly would intervene and get the matter settled.

Delayed payment of penalties had late fee attached to them.

Measures in place ensured that elected members of the village assembly do not escape fine or punishment using their influence. They were dealt with severely, if found guilty.

T Venkatesan from this panchayat town says even today candidates from the political parties visit this temple during election time to seek blessings.

The deity in the Vaikunta Perumal temple is referred to as 'Election Perumal' or the god for elections.

A DMK follower Kamala Kannan, a resident, points out another interesting factor -- whichever political party wins this constituency comes to power in the state.

Today, the temple town remains largely decrepit, dependent on sugar cane and rice farming, with just a few industries producing steel, cement and sugar.

When then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi was touring Tamil Nadu, along with his wife Sonia Gandhi, he visited the temple and enquired about the history and how democracy was practised here.

Seshadri, who knew some English, was to do the explanation. However, before he could do so, Sonia Gandhi interrupted and explained, for about 10 minutes to Rajiv Gandhi, the significance of the place, recalls Seshadri.

© 2025

© 2025