'Professor Christopher Alan Bayly was undoubtedly the tallest of his generation. For so many of his students who were privileged to be taught by him he was much more than the rarest of rare scholar.'

Professor Seema Alavi remembers a teacher who left an indelible imprint on Indian history.

I moved to Delhi's prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University, JNU, from the sedate and disciplined portals of Loreto Convent College, Lucknow.

In the early 1980s when the Communist parties of India inspired the urban intelligentsia, JNU became the nursery of radical Left politics. I too was brought up on cries of 'Imperialism down down' outside the classroom and ideas of anti-imperial nationalism and colonialism that dominated scholarly discussions within the lecture theatres.

That was my little world. And I enjoyed every moment of its self-sufficiency. Like most students I was embarrassed to even express the faintest desire to go to the bad imperial world for further studies.

Even more remote was the possibility of any fleeting thought that questioned the singular and uncomplicated history of Indian nationalism or modernity.

1983 changed all that. That year we were introduced to a new book titled Rulers Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1780-1870. The author was Christopher Alan Bayly.

The book stirred us intellectually like nothing before. It suggested that modern Indian history was incomplete without tracing its long connections with the early modern world. That colonialism may have had a longer more entangled history with Indian society; and that nationalism may not be crassly singular in its one and only anti-imperial avatar.

The predictably controversial nature of these arguments raised a storm in South Asian studies. Within departments of history students began to question the periodisation of Indian history into medieval and modern with its serious pedagogical implications and classroom logistics.

By 1987 Bayly's influential book had made the critical career decision for me: I was ready to leave for Cambridge to do a PhD with this esteemed professor. I was excited, but very tense. It was my first trip abroad. My first aeroplane journey.

To make it worse my father's instructions to wear black polished shoes when I met my new English professor, and to wrap myself in a heavy winter coat, gloves and muffler, did not make things any easier for me!

But even if I felt confident to handle all the logistics of travel and appropriate dress I was less than sure of how the first meeting with Professor Bayly would go.

As I walked up the staircase to his office at St Catharine's College I did not need to knock. He stepped out with his characteristic warm smile and offered to take my coat. Before I could ramble my well-rehearsed lines he was pouring hot English tea for me and talking about Lucknow, my family, and the beautiful University town of Cambridge.

Before too long we were walking on Kings Parade. As he walked me around Cambridge pointing to all the cafes and bookshops, and treated me to lunch he was for me no more the formidable Professor.

At the end of that first meeting I came home confused: He was truly exceptional in his warmth and generosity. But we had not talked about work. Nothing at all about South Asian history. All the reading I had nervously looked up in preparation for this meeting was in vain!

This first impression was not misplaced. Being his student meant that the normally lonesome and arduous process of PhD research work became an exciting voyage of discovery.

His wonderful style of demanding high quality work without making it seem as some mountainous task or grueling chore ensured that I enjoyed every moment of my four year stay at Cambridge. The pleasures were seamless: Wallowing in the archive, discovering the treasures at the University Library, listening spell-bound to a galaxy of visiting international scholars, participating in the weekly seminars, and most importantly sharing my ideas as the chapters of my thesis slowly took shape.

Every day was a delight. Every moment a learning process under the watchful and caring eye of Chris as we fondly called him. I remember calling him one afternoon from the public payphone of London as I had discovered a rare document at the India Office Library and wanted to instantly share it with him.

Chris was always there for me: Listening patiently as I rambled and lending that one line of wisdom, like a full stop, when I was finished.

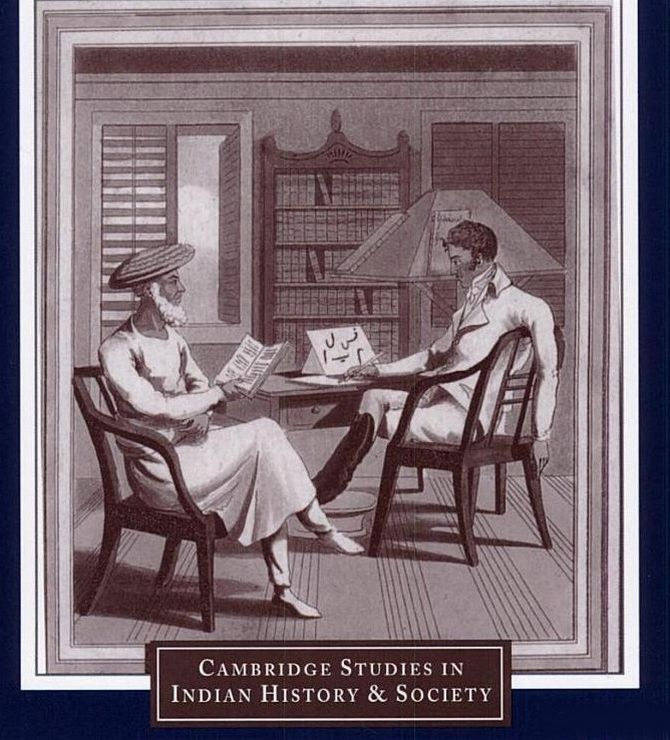

A master of the historian's craft Bayly could weave the most fascinating social history from what could go unnoticed as mundane and ordinary bits of information. His pathbreaking book Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 alerted us to the fact that British colonialism in India was entangled in webs of formal and informal information networks that welded pre-colonial India together.

As he went on to lay out the long history of India's information ecumene from the early medieval period he shifted the focus from official policy and State actors and put the spotlight on people and communities who worked in the shadows of Empire.

Merchants, pundits, barbers, midwives, holy men and ascetics who spanned across the length and breadth of the Subcontinent suddenly grabbed headiness as critical agents who made both the Mughal and the later British rule possible.

Bayly's influential writings on the role of social groups and communities who made the Empire possible and whose long histories he traced to the pre-colonial Mughal society had serious implications for the way we studied modern Indian history.

It was difficult now to talk of communalism and nationalism without referring to its long history and origins in the pre-colonial past. His more recent interests in global history and the new intellectual history of the Subcontinent urged South Asianists to look beyond the borders of South Asia and carve out a more connected history of the Subcontinent.

One that was not only entangled in local politics and society but also hooked on to global currents in Asia and Europe.

His untimely and tragic death in Chicago last Sunday, April 19, is a huge blow to South Asian studies. He was undoubtedly the tallest of his generation. His unparalleled intellect and ability to draw connections across Empires and political cultures was enviable.

Even more inspiring was his ability to push the frontiers of South Asian studies beyond the Subcontinent even as he steadfastly put the spotlight on the intricacies of its local entanglements.

But for so many of his students who were privileged to be taught by him he was much more than the rarest of rare scholar. We will also remember him as an exceptional teacher, a keen listener, a kind and generous friend whose English austerity concealed a warmth that touched and left an indelible impression on anyone who was lucky to have known him.

He will be deeply missed by all of us.

Seema Alavi is a Professor of History at the University of Delhi.

Top image: The book cover of Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870.

© 2025

© 2025