The nation has many individuals like Kuldip Nayar to thank whose idealism and honour has helped keep the country on the path of freedom and democracy, says Ambassador K C Singh.

The nation has many individuals like Kuldip Nayar to thank whose idealism and honour has helped keep the country on the path of freedom and democracy, says Ambassador K C Singh.

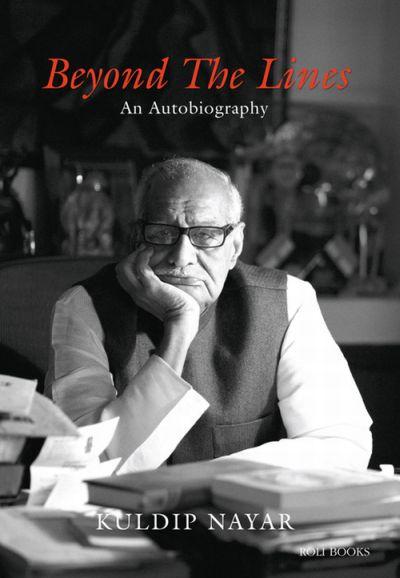

Kuldip Nayar's autobiography, Beyond the Lines, is an interesting testimony to an entire era -- from India's Partition and the birth of modern India as we know it to the UPA government.

It is largely chronological -- though occasionally, the reminiscing tends to relapse into a stream of consciousness, unusual for this genre. Nevertheless, his journey has been an eventful one, as he saw national life both from the outside as a journalist and then in multiple roles from inside whether as media adviser, informal counsellor or back again as a diplomat and finally as a member of Parliament.

The quality of his recounting is variable, revealing at times, superficial at others or sometimes downright inaccurate. The fact that an extremely nice man like Kuldip Nayar can also harbour prejudices shows he is human after all.

Six-and-a-half decades after Partition and three-and-a-half decades after the imposition of the Emergency, it is still important for these periods to be analysed and recorded by those who witnessed them, or as in the case of the author, were its victims. Those chapters are a must read for all, but particularly the youth as many of those who were the perpetrators of the Emergency are still in public life.

As George Santayana aptly put it, 'Those who cannot remember the past are destined to repeat it.'

Having had the opportunity to work with two successive home ministers as media adviser, first Govind Ballabh Pant and then Lal Bahadur Shastri, he throws light on the thought processes of these stalwarts.

Not enough material is available on Nehru's Cabinet ministers, their subtle jockeying for influence and the role of Indira Gandhi in the post 1962 phase. Was she the anointed successor or not of her father or her rise owed as much to fortune as to guile?

Nayar provides some missing narrative on how Shastri viewed her and the drama that occurred at Tashkent where Shastri died, hours after signing an accord with President Ayub Khan of Pakistan.

The narrative warms as he approaches the declaration of the Emergency in 1975. Although many others have written about this period, but his being at The Indian Express, which put up a stout resistance, gives new insights into the role of many in the media and the government, but particularly of the proprietor Ram Nath Goenka.

Where Nayar excels is his having maintained contact with the principal dramatis personae like Jayprakash Narayan. In his role as a journalist, as well as an activist having undergone incarceration, he could bridge many divides.

He makes no apologies for having actually mediated between warring personalities, though he may be overestimating his role. Politicians have a great ability to make each interlocutor feel that he is special and the only one they are relying on.

Perhaps it was inevitable that his persona as an activist for democracy and human rights was bound to overpower his role as a mere journalist. In a sense he became unemployable by any national daily when even Goenka started kowtowing to Mrs Gandhi after her return as prime minster in 1980.

As a confirmed liberal, an endangered species in India, he espoused many causes, mostly in defiance of public opinion. His efforts to help resolve the Punjab problem and the Kashmir issue, his consistently pro dialogue stance on Pakistan etc did not always endear him to the chattering classes.

His saga is of old world humanism, though he sounds at the end rather tired or even despondent at the state of the nation. In the chapter about his membership of the Rajya Sabha he demonstrates how a nominated member can impact the legislative agenda of the House, a lesson that most nominees never learn.

Where he was a mere onlooker the quality of the book flags as he lapses into clichEs or repeats inaccurate guesses made by others. An example is his analysis of the stand-off between President Zail Singh and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

His impression that he was the mastermind behind the strategy to catch the government on the wrong foot on legislation that was unpopular is wrong. I am witness to the President seeking the opinion of sundry legal luminaries, politicians and in-house advisers like me.

The Shah Bano case was in 1986, when the prime minister had still not lost his credibility and Muslim sentiments were a factor. The Postal Bill came in 1987, and had the entire public opinion ranged against it. Moreover by then the prime minister had been crippled by Bofors.

The President chose to strike when he felt the advantage had shifted to him. His reading was right and the government eventually backed off. On the Muslim Women Act 1986 they would not have.

His contribution to normalising the relations with the Sikh community in the United Kingdom as the high commissioner was laudable. He recounts the difficulties he encountered and the prejudice he had to fight. On the Babri Masjid, like former minister Arjun Singh, it is easy to demonise P V Narasimha Rao, the then prime minister. The reality was more complex.

Then there are obvious errors where the famous letter carried by External Affairs Minister Madhavsinh Solanki on the Bofors case was to the Swiss government and not the Swedish one as stated in the book.

Despite these glitches and drop in the quality of information or analysis in the last third of the book, it is a recommended read as it recounts the first-hand account of a veteran who saw much and experienced the highs and lows of national life.

The nation has many such individuals to thank whose idealism and honour has helped keep the country on the path of freedom and democracy.

Ambassador K C Singh, a former member of the Indian Foreign Service, served as joint secretary at Rashtrapati Bhavan during Giani Zail Singh's tenure as President of India.

© 2025

© 2025