| « Back to article | Print this article |

On the eve of the 1971 war between India and Pakistan, I was posted in Punjab. My battalion of Gorkhas was located at Ambala and had the task of defending a section of the border north of Amritsar.

I had never been to the Golden Temple and took the first opportunity to visit the shrine. Being a compulsive smoker, I had a packet of cigerettes on me. At the entrance itself I was told to deposit the packet in the locker and then go ahead.

During my first visit to this holiest Sikh shrine, I heard the shabad kirtan (devotional songs) being sung from the first floor of the Harmandir Sahib. Being an avid fan of Indian classical music, for me it was a treat to listen to some of the finest music, that too free.

From this time onwards, whenever I was passing through Amritsar I made it a point to visit the Golden Temple and spend some time there. It was always a rewarding experience.

It was quite common to see, at that time, that Hindu visitors to the Golden Temple far outnumbered Sikhs on a normal day. In my army days most of my close friends were Sikhs and therefore one was quite familiar with Sikh rituals and often visited gurdwaras as a matter of course on Sundays.

But less than 13 years later, I found myself again in Punjab, this time on the unpleasant duty of dealing with terrorists who thought that pulling out Hindus from buses and gunning them down mercilessly was their highest religious duty. As a participant in the painful but necessary Operation Bluestar, I can vouch that when General K Sundarji said that the Indian Army entered the Golden Temple with a prayer on its lips, he echoed the sentiments of all of us.

Today, when the memory of those nightmare years seems distant, there is an attempt to give a very different colour to the whole episode. Gulzar did that quite effectively with his film Maachis. The tragic consequences of that were seen in the suicide of a Sikh police officer (former Tarn Taran superintendent of police A S Sandhu) who had dealt with terrorism. It is therefore time for all Indians to understand the truth that led to a ten-year bloodbath in Punjab and not attempt to glorify the terrorists under the garb of human rights.

Most analysts agree that the troubles in Punjab began with the Nirankari-Sikh clash that took place on April 13, 1978, in Amritsar. The Nirankaris are a heretic cult that violates the basic tenets of Sikhism and yet claims to be part of the Panth. Forty protesters died in that clash and a feeling spread that the government was supporting the Nirankaris. It is noteworthy that at that time Punjab was being ruled by the Akalis. The violent movement that began initially as an anti-Nirankari agitation soon turned against the government and, later, Hindus.

The origins of the Punjab crisis and Sikh separatism go back to the British days. As in the case of Muslims, giving Sikhs a separate identity, not religious but political, was a part of the divide and rule policy. But the trauma of the partition of Punjab did much to wash off that myth and the Sikhs returned to the Indian mainstream.

The Akalis often used the slogan of 'Sikh Panth in danger' (not unlike the Muslim League's equally false and disastrous slogan of Islam in danger!) to garner votes, but consistently failed in their attempts. Sikhs, by the dint of sheer hard work, prospered and came to occupy a dominant position in many fields, including in the armed forces. A distinction needs to be clearly made between a distinct religious identity and political separatism based on religion.

Why then did Punjab erupt in the 1980s?

Several explanations have been offered. Some attributed it to the deprivation of the masses in spite of the Green Revolution. Others felt that the Akali frustration at their inability to attain political power (as the SC/ST Sikhs and Hindus combined to support the Congress) was at the root of the violence. Machinations by Indira Gandhi, who was credited with having deliberately created Sikh militancy to gather frightened Hindu votes, has also been floated as a serious theory.

But none of these explanations suffices to understand the widespread support that militancy enjoyed at its peak. To understand this phenomenon, one has to go back to the decade of the 1960s and the Green Revolution.

In 1965, when the US effectively used food aid to browbeat India, Indira Gandhi and her dynamic minister in charge of food and agriculture, C Subramaniam, fashioned a strategy to attain food self-sufficiency in the shortest possible time frame. The irrigated lands of Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh were targeted for application of miracle seeds, fertilizers and mechanisation.

The strategy succeeded and India became self-sufficient in foodgrain. But rising incomes and mechanisation brought in their wake social tensions.

In the hard work that intensive agricultural operations involved, the turban and the beard were seen as a hindrance. Sikhs in large numbers took to trimming or even shaving their beards and cutting their hair, both against the tenets of the Khalsa (pure) Panth. The hair and the beard are not mere external symbols for a Sikh, but a major part of his identity.

Worse, many took to smoking, a taboo in the Sikh ethos. A district like Amritsar, which has a majority Sikh population, became the highest revenue-earning district for cigarette companies. 'Paani piyo pump da te cigarette piyo Lamp da' was a catchy slogan that linked the smoking of Red Lamp cigarettes with water from the 'pump', subtly linked this symbol of the Green Revolution with smoking.

In travels through Punjab as an army officer, one was always welcomed with open arms. It was also common to share the charpoy and lassi with the farmers. During all these encounters, one frequently heard a lament from Sikh elders that at the rate at which people were deserting the faith, in a few years there would be no Sikhs left in Punjab.

The relationship between Sikhs and Hindus was such that the moment a Sikh shaved his beard and cut his hair, he became a Hindu. Sikh society felt insecure at the assault of this 'modernisation' and feared for the survival of its identity. This feeling was not confined to the villages but was commonplace even among the Sikh intelligentsia.

In this situation of fear and foreboding arrived Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale with his single-point programme of strict adherence to the Sikh symbols. His campaign against trimming of hair and shaving of beards found a groundswell of support amongst the Sikh masses. And he enforced his dictates with ruthless force.

His violent methods brought him into direct confrontation with the State and soon militancy began in Punjab.

But 'modernisation', the real threat, is a formless entity. So the violence first targeted the Nirankaris, then the government machinery, and then the Hindus. In the final stages, the terrorists turned increasingly against the Sikhs themselves and became predatory. It is at this stage that the militants lost support and were finally overcome towards 1993.

The situation was tailormade for Pakistan. It intervened with a generous supply of arms and ammunition and mayhem began in right earnest. The US and the UK also saw in this an opportunity to destabilise India, their long-term goal during the Cold War. The West used expatriate Sikhs as an instrument of its policy and gave shelter and support to all manner of terrorist groups.

Indira Gandhi saw this as a direct challenge to India's very existence and eventually decided to act, leading to Operation Bluestar. The rest, as they say, is history.

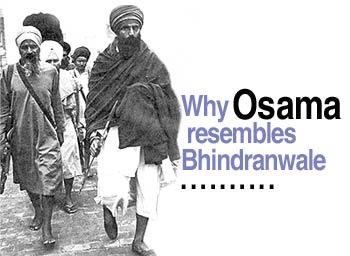

There is an uncanny resemblance in this to the Islamist terrorism that the world is witnessing today. Like Sikhism then, Islam today is afraid of modernisation and Westernisation. This also explains the wide support terrorists enjoy in the Muslim world. Osama bin Laden is a spitting image of Bhindranwale.

Like Sikh terrorism, the current wave of Islamist terror will subside once the terrorists turn predatory (as their recent attacks in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan indicate) and lose popular support. Only then will the world be able to deal with this modern scourge. Punjab does offer a valuable lesson.

Image: Uttam Ghosh