Maruti Warke's basic understanding illustrated how far outside the system most less privileged Indians are -- simple, innocent people barely but admirably eking out an existence, with almost no knowledge of their surroundings or owning even the basic smarts to go about life.

The same people who instinctively and often astutely vote governments into and out of office in New Delhi without knowing the entire reality of this country.

The folks who are actually the essence of India.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

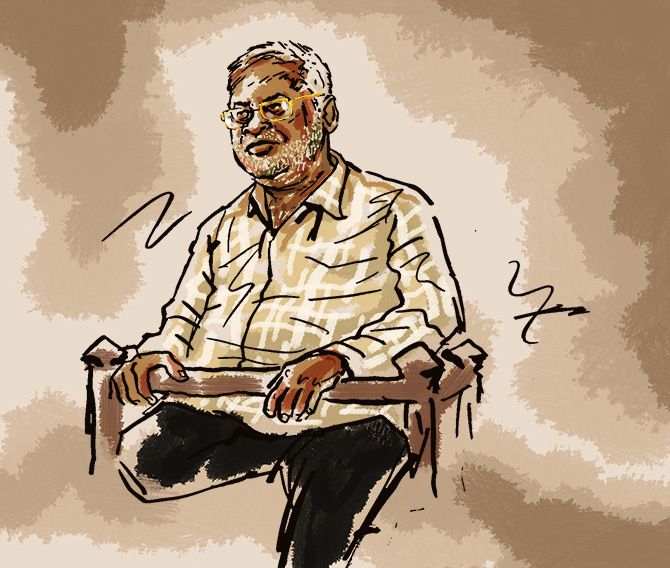

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Gargoti village in Bhudargad taluka, about 53 km from Kolhapur, Maharashtra, has approximately 3,500 homes, as per the last census.

Nearly half of its working population toil in the fields or have jobs in agriculture.

But literacy is well above the state's average at 85 per cent in this village town and the men folk are 93 per cent literate.

Clearly, Maruti Vithu Warke, 64, who hails from that locale in Kolhapur district and who took the stand on Tuesday, February 26, 2019, as Prosecution Witness No 36 in the Sheena Bora murder trial in Courtroom 51, Mumbai city civil and sessions court, south Mumbai, was not the best example of literacy that Gargoti had produced.

Simple-minded, clueless and mostly ignorant, in spite of the basic education he probably possessed, he was no ideal witness, even if he wasn't reluctant.

Largely ineffective, his gullibility and sense of confusion made him useful to both the prosecution and defence in a limited way.

Totally at sea in the court environment, it was not even evident if Warke had any grasp of what exactly he was in Courtroom 51 to do, although he had bravely embarked on this tough mission. His lack of understanding and poor comprehension skills were evident from the moment he began deposing.

But like many witnesses in this trial, he, perhaps, was brought in by the CBI for the sake of continuity -- so the case's narrative was not incomplete and moved logically from person to person. Each and every witness, whose life at any point intersected with Sheena Bora or the accused on those three or four fateful days in April 2012.

Uncomplicated and inadequate though Warke was, there was also something both refreshing and insightful about his testimony and cross examination.

His utter guilelessness swept into the courtroom a breath of fresh air all the way from rural Gargoti seven hours away.

Warke's basic understanding illustrated also how far outside the system most less privileged Indians are -- simple, innocent people barely but admirably eking out an existence and surviving in their dotage on probably a pittance, with almost no knowledge of their surroundings or owning even the basic smarts to go about life.

The same people who instinctively and often astutely vote governments into and out of office in New Delhi without knowing the entire reality of this country. The folks who are actually the essence of India.

How did the simple-minded Warke get caught in the Sheena Bora murder case?

Warke left his village in 1976 and journeyed some 375 km to come to Mumbai to seek employment and found work in India United Mills No One, Parel, central Mumbai.

When this cotton mill, along with a legion of landmark city textile mills, that were once the lifeblood of Mumbai, shut down, Warke was tossed out of a job.

He reinvented himself and found work in 2008 as a security guard in a firm named Vigilante. He was posted to Marlow building, where Indrani and Peter Mukerjea lived in Worli, south central Mumbai, and eventually went on to become the security supervisor, monitoring the work of four other guards there, of which he remembered only three names Shambhunath Kode, Subhas Parshuram and Shaligram Gupta.

Warke was on duty at Marlow, the evening Sheena Bora was murdered and on various days before and after, of which he had a sketchy, villager's memory.

A short, grizzled man, wearing a long cream checked shirt over dark slacks and black rubber bathroom chappals, who had now retired and moved back to his village, Warke seemed at least a decade older than the recorded 64.

Bespectacled, unshaven, white haired, with a mouthful of yellowed, broken-down teeth, the former watchman spoke in Marathi to the court. Cheerful and trying his best to be helpful, Warke unfortunately didn't have a whole lot of information to offer through his testimony conducted by CBI Special Prosecutor Kavita Patil.

Yes, he knew Peter Mukerjea and Indrani Mukerjea.

Yes, he knew that Peter was on the society committee at Marlow.

Yes, he knew they lived at Flat 19 and owned Flat 18 too.

Yes, he knew they sometimes stayed abroad in London.

Yes, he knew their former driver Shyamvar Pinturam Rai, Accused No 3 and approver -- "Sahib cha driver."

Yes, he knew Rahul Mukerjea -- "Sahib cha beta" who came to see Peter and he had let him into the building.

Yes, he knew Sheena Bora -- he had seen her along with Madam.

CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale to Patil wryly: "He has to name the Madams and Sirs. Every building will have so many Madams and Sirs."

Other than this not very insightful information, Warke offered, in Marathi, a rudimentary, uninformative account of the family's movements (whom he only referred to in the most respectful terms) during that period: "In April 2012 I was on duty as a security guard in Marlow. On April 23 Shyamvar Rai arrived in the building. On that day the whole day they were going outside the building and coming back. Yes, yes by car. On 24th also Madam went out and came back. On the 25th Sahib came."

After Warke acknowledged that Indrani and Peter were in court, Indrani's lawyer Sudeep Ratnamberdutt Pasbola spent 15 to 20 minutes cross-examining Warke.

The advocate, in an expansive, patient mood, a sardonic smile playing on his face, adopted a very gentle conversational tone with the retired guard, probing carefully the real extent of Warke's already visibly meagre facts.

These were facts, after all, disadvantaged by the enormous time that had elapsed between the crime and the trial.

The lawyer's aim, not at the expense of Warke, was to show how inconsequential his information really was -- just vague, sketchy, knowledge of residents of a building as its security guard.

Residents who would obviously have drivers, help, visitors and relatives and would quite naturally go in and out of the building in cars, as Warke had stated baldly in his thin testimony, because if they didn't do that, it would be abnormal.

For Warke the witness box was not very different from the chowk or a gathering place in his gaav and he got really comfortable in it. He shed his slippers, waved his toes about or squatted on the stool tucking one leg under his haunches.

His phone rang in between, much to the horror of the court policeman. A restless man, Warke would sit for a few minutes and then get up and pace from one side of the box to the next, pull up his shirt, hoist up his pants or fiddle with the water bottle next to the court stenographer, especially when faced with questions he was not sure he even understood or could fathom how to answer, looking utterly lost, the court experience proving daunting.

The court policeman, sitting next to me, cluck clucked quietly, muttering that Warke did not understand much.

Pasbola asked if Warke knew that 18 families lived in Marlow building and if each of the families had more than one car. Would he be able to recollect the names of all the families living at Marlow at that time? Did know the domestic help and who worked for whom?

Pasbola in Marathi: "You would not, for instance, know who was living in Flat 18 or Flat 14 or Flat 4?"

Warke thought for a moment. He tendered, obligingly and surprisingly brightly: "Sameer Tobaccowalla lived in No 14. And Dadabhai lived in No 3," showing that he should not be entirely underestimated.

There was a visitors's book at Marlow but Warke was not in a position to remember which visitors had come, when. Also, since as a supervisor he sat at the society office, situated near the garages behind, he could not observe who had come in and out of the gates of Marlow.

The former security guard agreed too that he had no idea of the make, model, license plates of the cars of the residents, which effectively meant he would not know who was coming in and out of building, from afar, if they were coming by car.

The society had a system of writing down the licences plates of the cars parked outside the garages every night, including those of outsiders. Warke had no knowledge then or now of which cars of outsiders were parked in the building on April 23, 24 and 25, 2012.

The security guards at Marlow did not ask the domestic help to make entries in the visitors's book and the movements of help was not monitored.

Pasbola in Marathi: "How many other visitors came to Marlow the day Rahul Mukerjea visited and who were they? Do you know their names or who they came to visit?"

Warke didn't have a clue. Nor could he, poor man.

Pasbola: "Did you know who was a relative or who was a friend? Can you describe who were the friends and who were the relatives of Mr and Mrs Mukerjea?"

The man from Gargoti neither knew nor remembered.

Once Pasbola was done, Peter's lawyer Shrikant Shivade had his turn with Warke. His objective was to elegantly disentangle Peter from the skeins of Warke's testimony.

To that end, he initially asked if there was any specific reason for Warke to have remembered the date Peter arrive in Marlow in late April that year. Or perhaps the arrival of Peter was an important fact because of the Marlow meeting (AGM) Peter was to attend as society chairman.

Warke's replies in Marathi were not conclusive and wandered about the countryside. It continued that way for successive questions.

The judge often took Shivade's queries and again rephrased them for Warke, not necessarily with better results, even if Warke earnestly tried to provide worthwhile answers.

What was conclusive was that he had not mentioned any details about Peter returning to Marlow on April 25, 2012 to the police, who first handled the case, when they questioned him at north west Mumbai's Khar police station twice.

If Warke's answers about most things were vague, the date of being questioned by the Khar police was tattooed in bold Arial Black 72 point size on his brain.

He repeated many times, with absolute certainty, like a mantra, that he had been called to the police station on September 1, 2015. He also stated that he had been called by the police once more on September 28, 2015.

Equally categorically and confidently, he declared he had been called by the CBI three or four days -- "teen kiva char divas" -- after he was first called by the police -- three or four days after September 1 -- when actually the CBI had only entered the scene on September 28, 2015, when they took over the case.

Shivade pointed out to the judge that Warke seemed to be certain of those dates, even if the sequence was skewed -- incorrect.

The judge looked at Shivade and slightly exasperatedly commented that it wasn't surprising Warke had mixed the dates up: "It appears he has been prepared. I have been recording witnesses's statements for 20 years."

In his statement to the CBI too there was no mention of Peter's arrival at Marlow or that fact that Rahul had visited. Warke insisted he had told the CBI.

Wrapping it up Shivade told Warke that he was falsely stating that he knew that Peter or Rahul had visited that day.

This part of the proceedings Warke was ready for and gave a toothy grin denying it.

In between, Shivade also made it a point to confirm with Warke if the garages at Marlow, including the Mukerjeas's garage, were visible from the flat of singer Sonali Rathod on the first floor.

The second witness of the day Nagpur's commissioner of police, Dr Bhushan Kumar Upadhyay, was not available, informed CBI Special Prosecutor Bharat B Badami.

Pasbola mumbled jokingly, on a day when 12 Indian Mirage 2000s had entered Pakistani air space that Badami always delivered: "Surgical strikes."

Peter's bail application was discussed. Shivade said he was waiting for Badami's arguments and progress on it.

Badami, grumpily: "You are always insisting on the bail."

Shivade: "Of course, it is about my (his client's) personal liberty."

"What personal liberty?" asked Badami, and in the next breath asked about "justice for Sheena."

Pasbola loudly: "What about for the accused persons?"

March 4 was chosen as the date of the next hearing.

The court had also received a plea for parole from Shyamvar Rai which read: 'Shriman mahoday Judge Sahib aapse namr vinti karta hu ki mujhe teen saal se zyada samay jail mein ho gaya hai aur meri ma ka meri vajah se mansik santulan bigar gaya hai (Respected Judge Sir I humbly request you that I have been in jail for more than three years now and because of me my mother has lost her mental balance).'

He said he needed to go home to his village (Danwa, Madhya Pradesh) to get her treated, as there was no one else to take care of her.

The former driver, who is lodged in Thane jail, further added: 'Aur me jail mein hone ki vajah se meri beti umra 11 saal hai bahut dari rahti hai uska padaiee mein man nahin lag raha hai pariksha nazdeek hai (Because I have been in jail, my daughter, now 11, is very scared and is not able to concentrate on her studies even though exams are nearby).'

Rai requested a month of parole to take care of these urgent personal matters.

Warke was headed back to Gargoti probably by a red ST bus with his son, who he said proudly was waiting below.

The judge and the CBI will weigh in on the plea from the man from Danwa in the next few weeks.

- MUST READ: The Sheena Bora Murder Trial

© 2025

© 2025