Will there be answers?

Will we ever know the truth about who murdered Sheena Bora?

Savera R Someshwar reports from the Sheena Border murder trial.

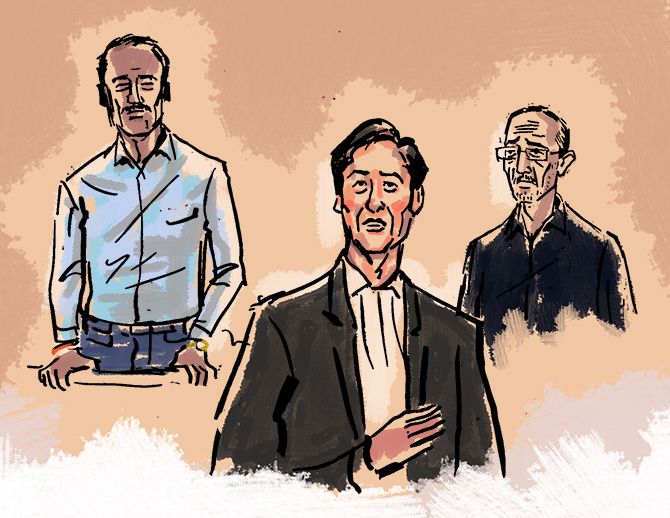

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

It's the little things that you don't think of.

Like a chair to sit on.

Like a bed to sleep on.

Like the freedom to meet your family and friends when you feel like.

Like savouring the first bite into a perfectly ripe Alphonso mango after waiting for a year.

Like picking the book you'd like to read.

Choosing the music you'd like to hear.

Binge-watching a show on your favourite OTT provider.

Watching a movie.

Or, maybe, if you are a pet lover, giving your dog or cat a little snuggle.

Watching the sun rise. Or set.

Yes, it's the little things that one always takes for granted.

When that freedom is lost, it is one the most terrible things that can happen.

Especially because, until it is taken away, you don't really know its value. But once it is gone, for every bitter minute that follows, you know what you have lost.

Sheena Bora, a 25-year-old just discovering Life, went missing on April 24, 2012.

It was allegedly the day she was, according to the confession of Accused No 3-turned-approver Shyamvar Pinturam Rai, a driver by profession, brutally murdered by her mother, Indrani Mukerjea, Indrani's ex-husband, Sanjeev Khanna and Rai himself.

Also implicated in the murder was former Star TV CEO and the man who launched INX Media, Indrani's husband, Peter Mukerjea.

In the years that have followed, Peter suffered a heart attack resulting in a 13-hour life-saving bypass surgery that required nearly 100 stitches.

Both Indrani and Sanjeev have seen their heath deteriorate. Indrani and Peter, who have been married for 16 years -- Peter has adopted Vidhie, Indrani's child with Sanjeev Khanna -- are on the brink of divorce.

All four accused have -- in a bid to get some semblance of that freedom back -- put in multiple applications for bail which, mostly, have been rejected

Peter's family, and Sanjeev's, have put their lives on hold to be there for their loved ones.

And, five years after her body was discovered, and over two years since the case went trial, a vibrant young life that was snuffed in its 25th year awaits justice.

Brick by slow brick, the CBI has been building its case Courtroom No 51 of the Mumbai Civil And Sessions Court, first helmed by Judge H S Mahajan and, later, within a few months, by Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale. While the three defence teams -- representing Accused No 1 Indrani Mukerjea, Accused No 2 Sanjeev Khanna and Accused No 4 Peter Mukerjea -- have been building theirs.

Judge Jagdale has been trying to speed the case along but, despite his best efforts, the wheels of justice apparently do move very, very slowly.

On May 29 and 30, when the rest of Mumbai looked to escape the broiling heat of the summer, the next panch took the witness stand in the Sheena Bora Murder Trial.

A tall, dark-skinned man whose hair has just begun to recede, Sandeep Pandit, son of Ravindra Pandit, had celebrated his 49th birthday earlier this month.

Here's how his story emerged, and evolved, under three able lawyers -- one for the prosecution and two for the defence. Neither Peter -- who is now back in jail, recovering from the aftermath of his massive surgery -- nor his lawyers were present in court.

The prosecution: The CBI

The familiar faces of the occasionally mercurial, white-haired Bharat Badami and the tall, sari-clad Kavita Pandit were missing from the prosecution's side of the table.

A little later, just after lunch, we would know why.

Instead, the fairly reserved looking CBI Special Prosecutor Ejaz Khan -- this is his second appearance in the Sheena Bora trial -- was at hand to question the new witness. His courtroom manner is restrained and non-confrontational as he finds his bearings in a case that has been going on for over two years.

Pandit, his bearing erect, explains in Marathi how he -- a resident of Sane Guruji Marg in central Mumbai -- was called to the Khar police station (the distance between the two places is almost 13 kilometres) on September 6, 2015, to act as a panch in the Sheena Bora Murder Trial.

And how, on September 7, 2015, he flew to Kolkata with the police to witness Sanjeev Khanna guiding the police towards the recovery of certain items that would tie him to the murder.

At the prosecution's request, he identifies Sanjeev Khanna in the courtroom.

The flight, recalls Pandit, left from Santa Cruz airport at 6.30 am and reached Kolkata at 8.30 am.

"We went to the traffic mukhyalaya (headquarters). Then we went to the local police station. We were given a Sumo car and a local driver." He also mentions two police officers, Ganame and Gaikwad.

The vehicle, says Pandit, the crispness of his blue shirt matching his demeanour, was "guided by Sanjeev Khanna."

After "deedshe-donshe (150 to 200) kilometres, Sanjeev Khanna stopped the car. There was a nursery there. Ek sattar varshacha manoos hota (There was a man there, about 70 years old)."

Khanna, says Pandit, showed them were certain items had been buried there. "We found a pair of tops (earrings), a purse and a pouch. They were torn." These items -- allegedly belonging to Sheena Bora, were shown to him and his fellow panch, Ravindra Narayan Aagwane -- and then "wrapped up" by the cops.

The always-efficient court clerk pulls up a cardboard box marked VPR 83/16 and quickly removes the tape had bound it shut. Its dusty innards show physical evidence that had been collected in the case, evidence that would hopefully, some day, help nail Sheena Bora's murderer(s).

For some time, there is silence, all attention focused on the petite lady clerk digging through the box.

She pulls out a transparent evidence bag of what looked like shoes.

"Yeh nahi, yeh nahi, yeh nahi (not this)," says Gunjan Mangla, part of Indrani Mukerjea's legal team.

"Ek minute (One minute)," the clerk quells her, "kadu tari dya (let me at least take it out)", so that she could search for the earrings, the pouch and the purse.

Mangla's smile is instantly conciliatory. The young lawyer from Accused No 1's defence team -- of the lawyers, she spends the most time with Indrani -- seems more relaxed in the courtroom now. She smiles more and does not seem as worn down by her demanding client.

The earrings remain elusive. Sanjeev Khanna's cousin, who has been a loyal visitor at almost every hearing, hurries to the front for a quick whispered conversation with Sanjeev's lawyer, Niranjan Mundargi.

Indrani, who is otherwise quite animated during court proceedings, seems disinterested. All you can see of her behind the aaropi (accused) box is her parted hair.

Sanjeev is frowning, his lips pursed. Is it because his sciatica is bothering him again, causing his lower back and legs to hurt, or is the struggle to hear the witness, who is answering in a tone barely loud enough for the judge and the lawyers to hear, wearing him down?

The conversational buzz increases in the ill-ventilated courtroom where everyone, except for the lawyers, the judge, his stenographer, peon and the clerk, has gone limp from the heat.

As the search continues, Khan nudges Pandit. "What happened next?"

"We went to the court," Pandit replies.

"You went somewhere?" Khan asked, somewhat enigmatically. Clearly, the witness has forgotten a crucial part of his testimony.

Sudeep Pasbola, Indrani's feisty trial lawyer, who spearheads the defence's 'cross', is quick to object, "Guiding the witness, your honour."

An argument erupts between Khan and Pasbola. Khan's eyes widen in irritation at the seeming ludicrousness of Pasbola's objection; Pasbola's body language screams annoyance at the prosecution's attempt to 'lead' the witness.

You could almost forget that these verbal cues are part of the complex dance that takes place in any courtroom; the animosity displayed is rarely personal.

Judge Jagdale seems inclined to proceed. Indrani's lead trial lawyer wants his objection put on the record.

Pandit, meanwhile, has had the time he needs. "We went ahead," he recovers his memory. "Some construction work was going on. Sanjeev Khanna led us to the back side. He showed us two pairs of Bata shoes, sizes five and seven. Nanthar they pack karoon gehtle (then they packed it up)."

The clerk reads from the CBI report, "Two pairs of gents shoes and one pair of lady's shoes." Then, she gingerly lifts the three items and places them on the little shelf that extends from the witness box.

"Only show the gents's shoes," Mangla jumps in. The witness has mentioned has only mentioned two pairs.

"Then we went to the court. Ganame saheb (of the Khar police station) and the others did the necessary procedures. I was sitting outside with Sanjeev Khanna."

Another CBI officer -- short, pot-bellied, wavy haired, dark-skinned, with a moustache that ends at the corners of his lips -- steps in at Khan's indication to help the court clerk hunt for the missing evidence.

Meanwhile, the clerk, at Khan's request, shows him the documents he has signed. Pandit examines them closely, signalling his attention to the task at hand with a severe frown.

"Are the signatures there?" Khan asks. "Are they correct?"

"Yes. Aagwane's and my signatures are there. In court, Gaikwad saheb signed."

By 3 pm, they were done and on their way to the airport.

"Is the man who showed you the way in the courtroom?"

Judge Jagdale's bushy salt-and-pepper moustache does a little wiggle as he smiles, "He has already identified him."

The judge's observation brings on Khan's first smile of the day. "It's for the second part. Otherwise they might claim the person was changed."

Even Pasbola can't stop his laughter.

Pandit identifies Khanna once again and proceeds with his tale. The team reached Mumbai by "12.30 am. They (the cops) dropped me on the highway and they went to the police station."

Meanwhile, the doughty clerk, with the assistance of the CBI officer, has managed to locate the elusive earrings. It is wrapped in white paper on which there is some writing. They are long, silver-coloured, seem shaped like a bottle. Some parts are covered with a green patina, probably due to exposure to the elements. They presumably belonged to Sheena Bora.

But Khan does not seem happy. He wants something else shown to the witness but Sanjeev's lawyer Niranjan Mundargi objects. "It has not been introduced or mentioned by the witness."

Some soil was collected from the construction site, which Khan's increasingly woolly-memoried witness has forgotten to mention.

"What happened there, at the second site?"

"We collected the shoes and some maati (soil)."

The defence lawyers -- Pasbola, Mundargi and their teams -- collectively shake their heads and sigh.

Even the judge is annoyed, "Kay he tumcha? (What's going on here?)"

Khan forges ahead, "Permission to show him the signature?" Every evidence bag has been signed off by the two panches.

"Doon polythene bags madhe maati aahe (two polythene bags filled with soil)," says the clerk, handing them over.

For some reason, Khan wants to show Pandit the shoes once again.

"It is in the statement, it is shown," the judge assures him.

"After dropping you, did the cops ever call you again?"

"The CBI called in October."

"In October 2015," Khan clarifies and asks, "Why did they call you?"

"About what happened," says Pandit.

"The same thing that you have now described?" asks Khan.

"Yes," says Pandit. "Singh saheb was there." The reference seems to be to CBI Investigating Officer Kaushal Kishore Singh, who along with Bharat Badami and Kavita Pandit seem have disappeared from Courtroom No 51.

The Defence: Sanjeev Khanna

Niranjan Mundargi would like to begin his 'cross', but the judge is pushing for a post-lunch session. Some of Judge Jagdale's colleagues have been transferred and it looks like he is either lunching or spending a few minutes with them.

Mundargi is persuasive. "15 minutes," he promises. "Else, we'll continue after lunch."

"Where" Mundargi turns to Pandit, "do you work?"

"Vashi market," says Pandit. "Then." (Vashi is located in Navi Mumbai.)

"Yes, yes," Mundargi smiles charmingly. "We are interested in then only."

Quickly, with his customary politeness, Mundargi establishes that Pandit then worked as a "private" security guard who wasn't sure of the of his employer.

"Balu, they called him," says Pandit

"You don't know his full name?"

"(Hesitatingly) Balu More."

He worked there for three years, Mundargi discovered, but had no appointment letter, no "kagaz-patri (documentation)" about his employment and took his salary in cash.

After three years, he quit because he no longer wanted to do night duty.

"Do you any proof about your employment?" Mundargi asks again.

No," says Pandit. "10 vyapari (traders) came together to employ me."

Mundargi then asks him about Akash Mangla.

"He is in the police. He's a friend."

"In which police station?"

"Naigaon (a town north of Mumbai, located approximately 22 kilometres from Pandit's residence at Sane Guruji Marg and approximately 65 kilometres from his place of work)."

"So he told you (Inspector Dinesh) Kadam (of the Khar police station) had called you?"

"Yes."

"That he had called for you specifically?"

"That he had called for me."

At which point, rather like how the interval pops up at an interesting point in a film, the court broke for lunch at 1 pm.

When the court resumed at 3 pm, CBI Prosecutor Ejaz Khan had an announcement. Introducing the members of his team -- he quickly rattles off the names of lawyers and CBI officers -- he told the judge, "Excerpt us, no one is allowed to touch the files of the Sheena Bora case on behalf of the CBI."

With that, the new CBI team continued on its first day at the Sheena Bora Murder Trial.

Mundargi is late, which allows us to catch up on the rumours surrounding the CBI change of guard. The judge, apparently, was not happy with the pace of the trial. Nor was he happy with the CBI's objection to every request from the accused.

Like, for example, Peter's request for a bed before he had the heart attack.

When an apologetic Mundargi rushes in, 10 minutes late, his face is flushed red from the afternoon heat.

"Did Akash come home to give you this message?"

"Yes."

Pandit says he rushed to the Khar police station and when he met Inspector Dinesh Kadam; Sanjeev Khanna was in the room, as was the other panch witness, Ravindra Aagwane.

Despite Mundargi's gentle manner, Pandit's demeanour has changed. Either the heat heat or the fact that he's been on the stand for a few hours could be getting to him; his stance is no longer as erect.

Somewhere between 4.45 and 5 pm, he says he signed the panchnama in which Sanjeev Khanna had confessed that he could show the places in Kolkata where he had disposed off certain items that would connect him to the Sheena Bora trial.

Half an hour later, when he was leaving the police station at 5.30 pm, he was told he would have to go to Kolkata the next day.

The next day, it took them "about half an hour" to get from the airport to the "traffic control mukhyalaya," Pandit tells Mundargi.

He says the building had "two or three floors" but can't recall its colour which could have been "white or yellow, like all buildings look..."

Mundargi laughs in surprise. "Not all buildings look the same... So you can't say for sure?"

"No."

Pandit does, however, recall a "football maidan" before the building.

Sometimes, the questions you hear in court make you question yourself. Would you remember the colour of a building that you visited just once, even if it was for an unforgettable occasion like being a panch on a murder case?

Do you remember the colours of some of the buildings you pass every day?

Don't look now, but do you remember the colour of the building opposite your doctor's office, whom you visit a few times a year?

Or the one at the corner? How many floors does it have?

If you were a witness to an accident, would you immediately write down the details so that you don't forget? Or would you, like most busy Mumbaikars, just move on with your life?

One wonders, sometimes, how witnesses remember.

As Mundargi's questions continue, Pandit remembers that he and Sanjeev Khanna were "sitting outside, building samor (in front of the building) while the cops went inside." He is not asked, and nor does he volunteer why the cops were in that building.

Their next destination, the police station, was 20 minutes away, he says.

"How did you go there?" asks Mundargi.

Pandit seems to be thinking. After a pause, he answers, "We came across the ground to the highway. They came to pick us up."

Mundargi: "So it is incorrect to say that you were provided a vehicle at the mukhyalaya."

Pandit nods carefully. Slowly, his memory seems to be flagging. He can't remember the name of the mukhyalaya or the name of the police station.

Judge Jagdale patiently translates the Marathi to English for the court stenographer.

Mundargi wants to know about the airline tickets. Pandit explains that, for the flight to Kolkata, he was given his boarding pass at the airport by Kadam.

Mundargi then casually poses the next question. "Were there journalists?" he uses his clenched fist to imitate the television media and their mikes, "waiting when you left and returned?"

"Yes," smiles Pandit as he quickly, almost proudly, answers, "But we didn't answer any of their questions."

Khanna, according to Pandit, was seated next to him on the flight and spent most of his time reading.

Sanjeev Khanna's affection for thrillers is now well known; his cousin regularly brings him a fresh supply of books.

Mundargi then makes the standard statement that follows every cross.

"You signed on these documents because your friend asked you to. It is my submission that you are lying on behalf of the CBI."

The Defence: Indrani Mukerjea

The next morning, Sandeep Pandit takes the stand in a dark blue shirt and jeans. A gold chain peeks through. His sun glasses rest comfortably in his pocket, one silver coloured rim holding it place. A faded holy thread is wound around his right wrist, a gold watch flashes on his left.

Pasbola, stance in place, asks his first question. He wants to know about Pandit's education.

"10th pass. 12th fail mahnoon 10th pass (I failed my Class 12 exams)."

"English vachayaka yetha ka? (Can you read in English?)"

Pandit nods.

Pasbola wants to know if there is a water plant in front of the nursery.

"There is a tanki (tank)," says Pandit.

"Not tanki, water plant," says Pasbola, letting a little impatience show.

"I don't know."

The tanki was on the opposite side of the road, says Pandit, but is unable to tell the lawyer how wide the road or how big the nursery was.

For once, the "don't knows" and the "cannot says" don't annoy Pasbola.

The tanki seems to be important. Later, the lawyer asks the witness if he has heard of "the Orsonic Free Water Plan at Bawli, 24 Parganas?"

"No."

"Did you recover anything from the water plant on September 7, 2015?"

"No."

"Did you tell the CBI that three pairs of shoes were found in the nursery?"

"Two pairs."

"And one pouch and tops?"

"Yes."

"How long were you there?"

"Half an hour."

"How many of you were there?"

"Six of us."

Pandit tells Pasbola that while there was a watchman, there were no workers in the nursery.

"Then you went to the court?" It was a clever question, designed to trip the witness.

But Pandit, who had goofed up the day before, was ready.

"No, we then went to the construction site," that, he said on Thursday, was about "5 to 7 minutes by car and would take 10 to 15 minutes if one walked."

There was "no security" at the construction site, he said, but there were "labourers".

"Pandit sahib," it's risky for the witness when Pasbola gets eerily polite, "Do you say you have said all this but the CBI hasn't written it. Do you know why?"

Pandit shakes his head.

"When you collected the shoes, you took some soil samples as well?"

"Yes."

"Naahi aahet (it is not there)," Pasbola tells the CBI prosecutor, probably referring to the CBI report.

"It is an omission," Khan admits.

Pasbola reads, "Sanjeev Khanna disclosed that some things that were kept in the office were taken to Kolkata. That he would show us where they are if he is taken there. Shoes..."

"Two pairs," Pandit interrupts.

"Documents." Pasbola repeats the word, "Documents. Tops. He will show us in Kolkata."

Judge Jagdale intervenes, "Did Sanjeev Khanna say that?"

"Yes," says Pandit.

"Did you tell the CBI?"

"Yes."

"Two (pairs of) shoes, 1 ear top..." Pasbola says.

Pandit nods and looks at the judge, "Pouch, purse ani maati (and soil)."

"Of these," says Pasbola, "the pouch and purse are not in court."

"Yes."

"These are articles that are easily available?"

Ejaz Khan is about to object. Pasbola grins, "Mundargi's junior (Sanjeev's lead lawyer is not in court) is insisting, so I am asking this question."

A few more standard questions follow. They establish that, before and after September 6, 2015, Pandit has never acted as a panch, been to court as a witness, has had a a case registered against him or been arrested. But, he has been a regular visitor to the Agripada police station.

Pandit's testimony raised some interesting questions.

1. Why would Sanjeev Khanna take three pairs of shoes, a purse, a pouch and a pair of earrings that could tie him to the Sheena Bora murder and abandon them in Kolkata? Why not burn them with the body? Why not chuck them into the vast Arabian Sea that hugs Mumbai? Why not abandon each shoe and each earring separately, at different places, making them that much difficult to find?

2. Why would the Khar police investigators call specifically call someone like Sanjeev Pandit, who stays near southern Mumbai and used to work in far-flung Navi Mumbai, to act as a panch in a murder case they were investing? Most of the other panches who have testified so far seem to have been passing the police station when they were called in to act as a witness.

3. Pandit consistently mentions two pairs of shoes in his testimony. The evidence box that is opened in court, if it is the box that only has evidence from the Kolkata trip, has three. The CBI report also mentions three pairs of shoes. So where did the third pair come from?

In his CBI statement, however, Pandit says he has stated to the police that three pairs of Bata shoes, two of size five and one size seven, and one top (earrings) were discovered there.

So why was he insistent on mentioning just two pairs of shoes in court?

4. Pandit's story changes. While answering Ejaz Khan, he says they went to the local police station in Kolkata where they were given a Sumo car and a driver.

Under Mundargi's probing he says they had to walk across the ground to the highway, where they were picked by the local driver in Sumo.

As does his estimation of the distance to the second location, the construction site. Pandit tells Mungdari it was a five to seven minute walk from their first location, the nursery.

To Pasbola, he says the distance is five to seven minutes by car and 10-15 minutes if one walked.

5. Pandit says six of them went to the nursery. If one had to tally this with the CBI report, which Rediff.com looked at, there were two inspectors, two constables, two panch witnesses, Sanjeev Khanna and the driver of the Sumo. Which would make it more than six people.

Will there be answers? Will we ever know the truth about who murdered Sheena Bora? One doesn't know.

But there have been a couple of changes since the CBI changed its prosecutors.

The defence lawyers are -- probably for the first time in this case, despite their repeated requests -- given the list of the next few witnesses. Four more panch are on the list, two of whom, Khan tells Judge Jadale, will be examined depending on who appears at the next hearing, scheduled on June 11.

And Sanjeev Khanna's appeal for a chair in his cell -- one that he offers to pay for -- is granted. Khanna has been complaining of back pain caused by sciatica.

In a way, it is a small thing. Sitting on a chair. Something that most of us take for granted.

© 2025

© 2025