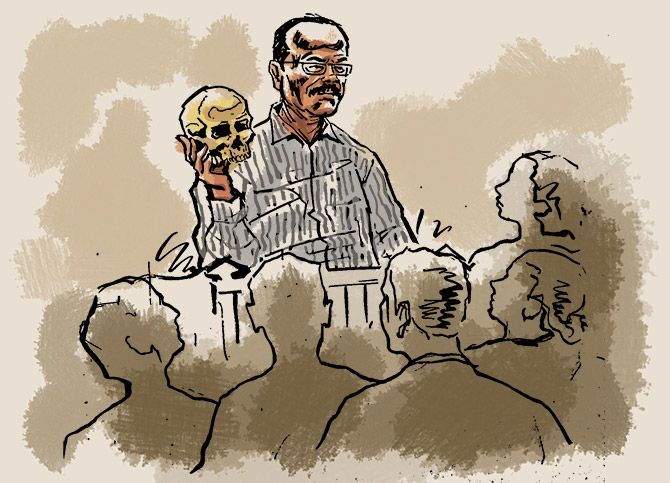

As Indrani, Sanjeev Khanna and Peter pass cupboard no 6 -- where the skull is stored -- what thoughts pass through their mind?

Savera R Someshwar reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Hidden behind the brown wooden door that guards the entrance to the Mumbai civil and session court's Courtroom No 51 is a dark blue steel cupboard, labelled No 6.

Crowning this cupboard are two steel trunks.

Like its 19 odd brothers that line the east and west facing walls of the courtroom, it guards the evidence from various cases that are presided over within the courtroom's walls.

Normally, no one pays attention to them unless certain evidence they store is needed, at which point the petite court clerk wrestles a grating cupboard door open to reveals its innards, usually filled with cloth bound bundles of evidence.

On the afternoon of Friday, November 8, Accused No 4 Peter Mukherjea's lawyer Shrikant Shivade -- who had returned to the courtroom after missing a scheduled hearing on November 4 due to cataract surgery -- was in the middle of his cross examination of Prosecution Witness No 58, Dr Shailesh Mohite, when he looked at the court clerk and mouthed, "Skull", his right hand, curved fingers wide apart, imitating a bowl.

At a nod from the lady clerk, the two male peons brought down the two trunks that otherwise rest peacefully above cupboard no 6.

One of them was brought over to the long lawyer's desk facing the clerk and laid on the floor. The taller peon walked past the barricade that separated the judge, his clerks and the stenographer from the rest of the courtroom. There, from another set of trunks he dug in for a key.

He re-crossed the barricade, bent and emerged with a light green packet. The younger lady clerk accepted it gingerly and there it stayed, a few centimetres from her left hand for the next half hour.

That sturdy green packet enclosed what is purportedly Sheena Bora's skull and, as it stayed in your line of vision, a chilling thought crossed your mind -- how many more human remains did Courtoom No 51, the evidence storage room next door -- where a grey cat balefully prowls -- and indeed the whole CBI court building hold?

The skull, and a certain number of bones, first made their appearance as part of the 'chief' (the prosecutor's examination) in the last week of August.

When the skull was displayed, Sheena Bora's mother, Indrani Mukerjea -- accused No 1 in the trial -- asked to see the skull from closer quarters.

As she, and Accused No 2 Sanjeev Khanna and Accused No 4 Peter Mukerjea, pass cupboard no 6 -- it is not something they can avoid -- during their appearances in court since, what thoughts pass through their mind?

Or has the whole process since their arrest in 2015 inured them, or forced them to take one moment at a time in order to survive, that they don't think about it at all?

On November 4, Indrani made yet another eloquent, if somewhat bizarre, appeal after her fourth bail application was rejected by the prosecution on the grounds that "her crime was very serious in nature and deserved a death sentence".

Her then husband Peter's brush with death -- that resulted in a live-saving, intensive bypass heart surgery -- left her wondering why even after she had shown symptoms of a brain stroke in September 2018 -- "and two millions brain cells are lost even after a minor stroke" -- she was not being granted bail.

"I have an irreversible terminal condition," she told the judge dramatically. "I might pop it any time."

She told the court she didn't want to die before her time because of the indifference of the prosecution. "They have decided on my death sentence."

She needed bail, she said, so that she could research her illness and consult doctors. A police escort and a visit to a private hospital would cost her "Rs 38,000" a day, a sum she said she simply could not afford.

She said she had been in jail for over "50 months for a crime I have not committed", that she had no "criminal antecedents" and "it was now time for the court to give her the benefit of the doubt".

The usually Judge Jayendra Chandrasen bristled at the implication that the case was dragging on because of the court and that he was giving the prosecution the benefit of the doubt.

"Each and every time," his voice rose a few octaves, "the court is insisting that the case proceed quickly. The court has urged that the case be finished soon. The court had mentioned time and again the plight of the undertrials."

"Why is the court only insisting? If you are pointing a finger at the court, we will also look at how many times the defence lawyers have not been available and how long the defence has spent over the cross."

Indrani quickly assured the judge she was making no such accusation and equally quickly moved on to state that her court-mandated quarterly examination by a panel of expert doctors had not taken place since the fourth quarter of 2016.

"No medical reports have been submitted as required to the court because there has been no examination."

Her voice broke. "I haven't done this (the murder). I haven't done this."

Red-faced and red-eyed, she continued, "I have a young daughter. She turned 18 the day after I was arrested. She is 22 now. She was mugged at gunpoint in Spain. They took her passport. She is traumatised by what has happened and is under psychiatric treatment. I am not able to be there for her. I will show you proof. I will produce the letters written by my daughter that have been sent to my lawyers if you wish."

How does a mother cope with the death of one daughter and the danger another finds herself? Does she mourn the death of the one she is accused of cold-bloodedly murdering as she worries about the other, younger, one who has to cope with the fact that the parents -- her mother, adopted father and biological father are behind bars -- accused of snuffing out the life of her half-sister.

Indrani's lawyer, the feisty Sudeep Pasbola, has finished examining the prosecution most credible, and most impressive witness yet, Dr Shailesh Chintaman Mohite, professor and head of the department of forensic medicine at the Topiwala National Medical College and the attached B Y L Nair Hospital.

On November 8, Peter's lawyer Shrikant Shivade took his turn at chipping away at Dr Mohite's testimony.

Shivade began by asking if the CBI officers took a statement from the doctor before or after his reports were ready. Dr Mohite had prepared two reports, one dated August 28, 2015 and the other dated September 2, 2015.

While Shivade's questions were in Marathi, Dr Mohite chose to reply in English, with a rare smattering of Marathi.

Dr Mohite said he was questioned by a team of doctors at the CBI, which led an exchange of words between the judge, the lawyer and the witness.

Judge Jagdale: "The team of doctors came from the CBI?"

Dr Mohite: "I don't know who appointed whom."

Shivade: "Doctors are not allowed to interrogate. A CBI officer has to do it."

"Pudhe baghu ya (let us consider this later)," the judge patiently chivvied Shivade along.

Unlike the cross-examination by Pasbola, there was a certain amount of friction between the doctor and Shivade.

Under Shivade's deft probing, the witness revealed that while he and the team of doctors "observed and measured" the skeletal remains, he personally keyed in the observations into the computer. There were no interim notes taken nor was each entry given a date or a time; a point that Shivade underlined.

The report was dated September 2 -- the date on which it was printed and signed, clarified the witness, but work began on August 28. Dr Mohite would carry out his forensic duty in the Sheena Bora case between lectures, exams, other post- and ante- mortems when he had the time.

The report aimed to answer questioned raised by the Pen police station, under whose jurisdiction the bones of Sheena Bora were discovered near actor Ranjeet's bungalow in Gagode Khurd in 2012, re-buried as unidentified and dug up once again after Accused No 3-turned-approver Shyamvar Pinturam Rai revealed it was where they took Sheena Bora's dead body and attempted to burn it.

The questions included:

- Was the skeleton that of a man or a woman?

- What was the age of the deceased?

- How long ago did the person die?

- What was the exact cause of death?

The doctor wanted to volunteer information, which did not make Shivade happy.

"If he wants to volunteer," Shivade told the judge, "it has to be related to my question."

"Yes," Dr Mohite said unsmilingly. "I want to volunteer." On a priority basis, the bones which gave the maximum information on age and sex were examined first.

Dr Mohite submitted a second report, dated September 5, work on which began on August 31.

The reports were sent to the police on September 15, 2015.

Shivade challenged the delay, saying that since it was an urgent police request it should have been complied with more quickly and the report sent as soon as it was ready.

The doctor stayed firm that there was no policy about sending the reports immediately "We don't post or send the reports. The police come and collect it."

"I will show you the rules later," said Shivade.

"Doesn't JJ (hospital) have one of the biggest anatomical departments in Maharashtra?" he next asked.

When the doctor agreed, Shivade wanted to know how many "forensic reports" are prepared at JJ every year, whether it was 500 or 600 or even a hundred.

"No. 10-15."

At Nair, where he worked, Dr Mohite told Shivade "1-2 skeletons were examined in some years, in other years there were none."

Dr Mohite seemed to take pride in the hospital where he worked; after agreeing he had visited JJ's radiology department, before which he explained to Shivade that anatomy and forensic were different departments at JJ, he said, "We (Nair hospital) do CT scans of dead bodies at well."

Which gave Shivade the opportunity to pounce. "Doesn't a CT scan give exact measurements of the skull and bones?"

The fencing match between the two began in earnest.

If Dr Mohite parried saying radiology machines were constantly being updated and he was not aware of the exact details, Shivade asked why he didn't know and how far back did his awareness of the radiological machines go?

"Ten years."

"So 10 years ago, were radiological machines able to record bone measurements?"

"I don't know."

Shivade tried another tack. He asked the doctor if modern techniques should be applied during forensic investigations since the result would mean life or death for the accused.

When Dr Mohite agreed, Shivade wanted to know why the doctor relied on manual measurements of the bones, where the scope of error was greater, instead of opting for mechanical measurements.

The discussion, which bordered on the gruesome, was strangely dispassionate. "It is difficult to take the exact measurement when there is flesh on the bones." But yes, a CT scan of a skeleton could be done.

Was it just a matter of blindly following laid down procedure or is a CT scan a better way of measuring bones. As a layperson, one does not know.

But Dr Mohite was clear that it was not correct to say a radiological examination was better than a physical one when it came to measuring bare bones.

"It depends on the operator."

"Doctor," Shivade face expressed shock at the doctor's seeming prevarication, "asa naka karu (don't be like this). Then doesn't a physical examination also depend on the operator?" The giggles in the courtroom made the two protagonists smile. "Sorry," said Shivade. "The examiner."

Patiently, much like a dentist extracting a stubborn tooth, Shivade got Dr Mohite to agree that the person who operated the radiology machine at Nair Hospital was "well-qualified" and that computer software delivered measurements that were accurate upto "micro-millimetres", something that is "difficult to do by hand".

Shivade next focused on a patch of skin with hair, collected from the alleged murder site at Gagode Khurd, and sent to JJ. A patch of skin -- 7 x 6 x 3 cm -- that, like the skull and the bones, allegedly belonged to Sheena Bora.

The senior lawyer's next question had everyone grinning and examining the back of their palms.

"Normally, the dorsal portion of the palm (wording that was arrived at after some discussion and pointing at the back of the palm), the fingers, will have no hair?"

"Perfect," said the professorial Dr Mohite. "The hair will measure in millimetres, varying from 5 to 12 mm. There will be variations according to age and sex."

"The hair is normally more in male and less in female."

"Could be," said the bemused doctor.

The skin the doctor examined was "dried, hardened, leather and hairy (hair length up to 1 cm)." The report says the skin could come from "the chest or any of the extremities," said the doctor, which Shivade was quick to point out "included the dorsal palm."

He then wanted to know if such skin could belong to a sophisticated, urban, young woman, which left the doctor embarrassedly confessing that he had not examined the hands of sophisticated, urban, youg women.

Even the judge's bushy moustache could not hide his smile.

As the discussion on hair length continued, and the witness said that hair on the fingers could be "0.5 cm to 1 cm long", Shivade turned to judge with a "Even I don't have such long hair and me purush aahe (I am a man)."

Even the histopathological examination of the skin -- which was undertaken after to doctors could not come to any conclusion -- did not reveal of the skin belonged to a male or female or, for that matter, to a human being or an animal.

"We sent it for DNA," said the doctor.

"I will come to the DNA," assured Shivade.

"Come at 2.45 (pm)," grinned the judge, as the court adjourned for lunch.

Post-lunch, Dr Mohite agreed that that "articles" sent to him were "examined minutely and carefully." The "articles" included the exhumed remains that were sent to the JJ hospital in 2012 and the remains re-exhumed under Dr Mohite's supervision in 2015.

Like he said in his 'chief' to the prosecutor and in his cross-examination by Pasbola, Dr Mohite repeated that "remains from JJ do not match the remains of the exhumed (2015). All the teeth do not belong to the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw)."

There were five teeth in the JJ sample, but only "two empty sockets were observed in the mandible on the left side. JJ's sample included a tooth which was sectioned longitudinally. I found it highly unlikely that such a tooth came from the place of offence."

No skin tissue found on the samples exhumed in 2015. Nor, Dr Mohite added, was any similarity found in the burnt area between the samples.

"The doctor at JJ (Dr Sanjay Thakur, who performed the post mortem in 2012) had examined the bones, but did not mention the names of the bones or identifiable burnt pieces of the bones."

He also stated that though Police Inspector Suresh Mirghe's letter from the Pen police station mentioned that they had sent the bone of the right hand, no such bone was found in the JJ sample.

The doctor continued, as he had done through the entire duration of his presence in Courtroom 51, to succinctly dictate and spell words for the benefit of the court stenographer, possibly making this one of the cleanest transcripts of the case.

Like Pasbola, Shivade's next arrow aimed at discrediting the medical method Dr Mohite chose to opt for examining the bones.

Diving into anthropology, he began by listing various races -- "Caucasian, Mongoloid, Negroid and Indian (incidentally, the 1951 Census of India has done away with racial classifications)" and how each race's bone structure varies depending on age and sex.

Listening bemusedly to Shivade's list of races, Judge Jagdale asked. "Azun kay rahile ahe? (Is anything left?)"

The senior lawyer then grilled Dr Mohite about when the Karl Pearson formula -- which was applied to examine the bones -- was derived (the 1800s, which Dr Mohite did not know, but, after checking his notes, said it was mentioned in an article in 1889), what database Pearson used, whether he only considered white and black people (Wikipedia says he considered only white men and women), whether he used Indian samples, which country Pearson belonged to, what his qualifications were and whether Karl Pearson was the name of one or two people.

To all of which the doctor either replied, "I do not know" or "I don't recollect."

A gruelling 20 minutes had passed and Shivade rubbed his eyes, which reminded him that he needed to use his scheduled eye drops.

Post-eye drops, Shivade waded in deeper, outlining that people from different places in India have different race characteristics, which impacts their stature (height).

He also pointed out that "over centuries, the stature of human beings has changed", implying that the Pearson method, derived in the 18th century, would not offer the right results in the present age.

Dr Mohite refused to be disturbed. "The margin of error is 2 to 4 cm on either side."

Referring the testimony that the body was burnt, Shivade asked if the doctor agreed that "inflammable substances cause more damage to human bones than corrosive substances. When bones are burnt, the water content evaporates and the bones can shrink, causing a difference the bone size."

Dr Mohite agreed, which gave Shivade ammunition he could use later to discredit the skeletal remains.

Shivade wanted to know why the doctor ignored the uniform guidelines for post mortem and exhumation that mandate collecting soil from above and below the body/bones and control samples from a distance.

Dr Mohite said "it was not the doctor's role."

Soil collection is important because its pH value (which determines how acidic, basic or neutral a substance is). Since, in this case, the soil was not collected, its pH value could not be determined.

Again, Shivade was the dentist and Dr Mohite the reluctant patient who admitted "pH value is one of the factors that affects the rate of decomposition and that the human body is acidic."

But he refused to agree that the pH value plays an important role in determining the estimated time since death.

While Shivade underlined that the time of death was estimated without considering the pH value, no questions were asked about how much of an impact exhuming and re-exhuming a body affects determining the estimated time since death.

He did, however, ask Dr Mohite if this was his first exhumation.

"I have done other exhumations, but do not recall if it was before or after this."

The anthropological and biological discussion continued, with Shivade asking Dr Mohite if he was familiar with Krogman's book on the human skeleton (Wilton M Krogman's Human Skeleton In Forensic Medicine was first published in 1962.)

The next lesson was muscle marking (where the muscle attaches to the bone).

Offering examples of a strong Negroid female have better muscle marking than a weak white male or the taller Negroid or Caucasian population to a smaller built India, or that a sportwoman or someone who is a fitness enthusiast will have prominent physical muscle attachments, or the fact that the method applied did not factor Assamese or Bengali population (Sheena Bora was petite and from Assam), or that hormonal or general health could affect the results, Shivade attempted to get the doctor to admit his report may be "erroneous".

Shivade also questioned him about anthropological landmarks (a set of small squares used for face identification) and if it was different for "different populations".

Dr Mohite didn't know.

Shivade wanted to know how the sex of the bones was determined.

Dr Mohite said they used "Krogman's table of frequency. With the skull alone, with 90 per cent frequency, we can tell the sex."

Again, Shivade pointed out that Dr Mohite did not know the database on which Krogman's table was based.

Now it was time for the skull, that Shivade wanted and which had found its way back into the steel trunk (the young lady clerk probably didn't want to look at the green packet and its gruesome 'article'), to enter the picture.

He took Dr Mohite back to Gagode Khurd.

"Wasn't the retrieval of the skull an important finding? Shouldn't it have been photographed? Did you tell any photographer? According to the guidelines photos should have been taken with a scale."

None this had been done through Dr Mohite had examined the bones at the venue with a magnifying glass. He did also maintain the chain of custody, with the list of "recovered articles being written down by Dr Sumit Sonawane, since I was wearing gloves."

Dr Mohite stopped the exhumation after they recovered 86 of the 206 bones that form the human skeleton. This did not, however include the hyoid bone (located just about your Adam's apple), even though the police said in 2015 that they suspected death by strangulation.

Shivade repeated Pasbola's argument. "The hyoid is important? It has tremendous medico-legal significance in cases of strangulation?"

"Yes," agreed the doctor.

The discrediting of the witness continued, though Dr Mohite continued to display immense dignity.

Shivade pointed out that Dr Mohite had never been published in the prestigious Index Journal nor had he ever been peer-reviewed. He added that, in none of the 10 research papers Dr Mohite had published, was he the first author.

Shivade now wanted the skull handed over to the doctor.

The clerks removed a yellow packet from the green one and handed it to the doctor.

"Do you want me to remove it?" the doctor asked Shivade who nodded.

The doctor held the yellow, mud-stained skull gently; the mandible, presumably, was still in the yellow packet.

The doctor explained that he used "anthropological measurements" to determine whether the skull was "bigger" or "smaller" and agreed that there are different grading systems to classify a skull based on "anthropometric measurements" (used to measure the shape, size and composition of the human body).

Dr Mohite was at his professorial best when he explained that antropometric measurements "are taken between anatomical landmarks."

He agreed there were no black (burn) marks on the skull and offered a dignified refusal when Shivade wound up his cross, accusing the doctor of preparing a report that said what the police needed.

He implied that, since many senior officers, including the commissioner of police, were involved in this investigation, and there was intense media interest in the case, the good doctor may have been under tremendous pressure to falsify the age and sex of the skeleton.

Surprisingly, Niranjan Mundargi, the lawyer for accused no 2, Sanjeev Khanna, who is also facing murder charges, chose not to examine the witness and did not make an appearance.

The next hearing, on November 19, will see a new witness, Dr Shrikant H Lade, the assistant director at the Forensic Science Laboratory at Kalina, north west Mumbai, where some of Sheena Bora's alleged remains were sent for examination.

And Sheena Bora's alleged skull, double-packed in yellow and green envelopes, went back into the steel trunk, which was quickly hoisted once again over Cupboard No 6.

Everyone was in a hurry to go home.

© 2025

© 2025