He was getting fruits, but no implement to cut them with.

He told the judge, sadly: "I have tried and it is very difficult, your honour."

His statement quickly brought up the imagery of Peter trying to cut a pineapple with his teeth or a papaya with a pen or a toothbrush.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

A trial in India is a true behemoth.

It is almost like an extremely large and powerful beast or a creature, as the word suggests, with a life and identity all its own.

You can't see it.

Or classify it.

But you can feel it.

Especially its demands.

It lumbers along, clearly its own boss.

Fed court dates, and masses and masses of paper/information, with regularity, it plods ahead moodily.

The direction in which it is headed is anyone's guess. It has a mind of its own.

Mainly there is nothing predictable about this behemoth for all those caught up in its path or observing it. The power belongs entirely with the behemoth.

The Sheena Bora murder trial is no different.

Who controls this particular Mr Behemoth?

With what statistics can you characterise it?

How many days will it last?

How may hearings will it require? How many people will finally depose?

How many people's time and lives will it hungrily swallow up?

The size and breadth of the trial is finally unknown.

The beast defies description or direction.

When you are sitting in Courtroom 51 -- as one was, on an unusually warm Thursday, October 17, 2019, waiting for a hearing to begin (it usually chooses its own time to start, the mathematics of it also equally incalculable) -- you are assailed by slightly resentful feelings of being unmoored, all because of the demanding Mr Behemoth.

How many more days will you be there each week? And what days?

Could there be chance of taking leave next month without missing too many days of the trial?

What percentage of your life will Mr Behemoth finally greedily and self-importantly consume?

Of course, there are no answers.

Don't even expect them.

If Mr Behemoth's arrogance is so intolerable for me, how much more tedious is it for those whose life fortunes are totally tied up in his conceit and capricious nature, be they the accused, relatives of the accused, witnesses or lawyers.

These and further thoughts were romping around irritatingly in the mind as one sat waiting in CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale's courtroom at the Mumbai city civil and sessions court, south Mumbai, for the delayed jail van of Accused No 1, Indrani Mukerjea to arrive and for the hearing to then begin. The judge was also patiently waiting.

The other musings were on a topic one had dwelled on so many times -- the shabbiness of the sessions court building and its courtrooms. Some of Courtroom 51's saggy, broken-down chairs had finally given up the ghost. They had been replaced by a few white plastic chairs. Chairs were still too few, too uncomfortable and the fans too slow or even slower.

The renovation job the building had been undergoing was still continuing at an astonishingly un-rapid pace. A workman was outside the window lethargically doing what appeared to be either painting or cementing, without an attached harness -- no safety precautions were being followed even on court premises.

When, in a country as successful as India, will adequate money be invested in its courts, if not its prisons (one ambulance for 3,000 plus prisoners in a jail)? It is the need of the hour -- to lend the requisite dignity to our valuable judges and our justice system.

On Wednesday and Thursday Indrani's advocate Sudeep Ratnamberdutt Pasbola spent cross-examining forensic witness Dr Shailesh Chintaman Mohite.

Three hours Wednesday and an hour Thursday were devoted to verbally fencing with the doctor over countless issues.

But right till the end it was a very civilised duelling match. You could practically see the white gloves and the lovely finesse.

Medical evidence has the highest value and importance in a criminal trial. A 2007 Supreme Court order underlined that when it stated: 'Medical evidence will assume importance, while appreciating the evidence led by the prosecution and will have priority over the ocular version and can be used to repel the testimony of the eye-witnesses'.

Forensic experts, especially of the seniority of Dr Mohite, who is professor and head of the department of forensic medicine at the Topiwala National Medical College and the attached B Y L Nair Hospital, central Mumbai, are very few in the country. His views carry therefore much gravity.

Hence Pasbola's investment of time and detail and careful respect in his cross-examination of Dr Mohite was particularly strategic.

Discrediting the opinions of such a learned expert -- who had appeared in numerous court hearings including those related to Mumbai's 26/11 terror attack (before the Pakistani high commission) and other terror attacks -- is tricky business and Pasbola had to proceed as if he were treading on egg shells.

He was marginally successful in skilfully introducing some elements of doubt, specifically by detailing, before the court, the limits of Dr Mohite's knowledge. Limits due to no fault of Dr Mohite's but the inadequacies of the system, which lacked the latest techniques, methods and knowledge for a forensic expert to draw on.

Dr Mohite's wins were more subtle. Like previous days his authority and professionalism won each time, hands down. It was almost impossible to doubt the veracity and honesty of a specialist of his calibre, especially one who conducted himself with such certainty and dignity.

The proceedings had its high points of amusement/excitement when egos clashed. Like, for instance, Pasbola met his match in eloquence. So good was Dr Mohite at constructing and verbalising his answers for the court records -- spelling out nearly two words per sentence -- that even the judge began to lean on the doctor for his dictation.

This didn't go down that well with Pasbola. There were little tussles on what actually went on the court record, with the lawyer discounting portions of Dr Mohite's verbose, exacting replies with 'My lord, let my answer may be taken and then (we can add) the witness volunteers'...

Often when Pasbola mispronounced a word, Dr Mohite would come back with the right pronunciation, slightly emphasised. And like it was a highfalutin' medical spelling bee in progress, one became aware how good Pasbola's medical spellings were too.

Pasbola's successes were not spectacular and rotated around the following points:

1. Sex and age of the victim based on Dr Mohite's examination of bones: At every point, and for many a bone, the lawyer debated with the doctor on how he had come to his deductions about age or sex based on the bones and questioned the chances of variation as per racial and regional differences.

For instance, he asked Dr Mohite: "Doctor I put it to you on the basis of the clavicle (collar bone) alone sex cannot be determined. A person (who is male) of frail health -- not like us (laughs heartily) would have the same dimensions of the clavicle?"

Dr Mohite: "I am not aware."

The judge murmured: "A hypothetical question."

And so it was for the ulna, radius, tibula, fibula, femurs, scapula (shoulder bone) and the glenoid cavity, which is a part of the shoulder bone.

Pasbola delved into what were the key inferences that made Dr Mohite believe they were female skeletal remains, apart from a slender and small size, which he felt could apply to a male too of delicate, effeminate build.

Pasbola: "Now your determination that it was a female was primarily based on muscular markings?"

Dr Mohite: "And the height of the glenoid cavity."

Pasbola disputed what exact height of the glenoid cavity pointed to the fact that the bone belonged to a female and pointed out the variations that might occur. He asked Dr Mohite to provide sources for this deduction -- which textbooks could back up this hypothesis. Dr Mohite named a few and cited the bible of anatomy: Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body.

Pasbola mentioned that he had never been able to get his hands on a copy of Gray's because he said disgustedly to the judge, doctors would never give him a copy.

Dr Mohite promised to bring his copy to court with xeroxes of the relevant portions (and later gift a copy to Pasbola) and also mentioned that they had relied on the view of Dr Sumedh Ganpat Sonavane, who accompanied Dr Mohite to the exhumation in Pen and "who was the anatomist on the team."

2. The quality of DNA extracted: Pasbola had several questions about the possible poor quality of the DNA extracted.

Pasbola: "The left femur bone (thigh bone) was sent for DNA analysis also two maxillary second molars (rear teeth). They were sent for analysis on 31/8/2015 even before the compilation and completion of this report?"

Dr Mohite: "We had finished examination of left femur, hence we sent it."

Pasbola: "You were in a hurry to send it?!" There were a few laughs.

Dr Mohite explained that the best quality and amount of DNA was found in the long femur bone and in the teeth and hence their urgency in sending these items for DNA sampling.

Pasbola asked why adequate and interpretable DNA samples were finally not drawn from the femur and the teeth.

Dr Mohite said he was not aware they were not able to draw interpretable samples. And he did not agree that the erosion of the bones or effect of burial of bones would have an effect on the DNA extracted.

3. Stature of the person to whom the skeletal remains belonged: Pasbola wanted to know the process by which Dr Mohite estimated the stature based on examination of bones.

Pasbola: "In this report you have used the Karl Pearson's formula for estimation of stature (20th century British mathematician and biostatistician who derived reconstruction formulae for living stature from dry bones)? Is this the only estimation?"

The lawyer wondered too about the variations between formulas (given that Pearson's formula was about the white race).

Dr Mohite said there were many ways to estimate stature, but Karl Pearson's formula was most "widely used."

Pasbola questioned Dr Mohite about what data he had to prove the accuracy of the Karl Pearson method. Dr Mohite refused to entertain that line of argument, stoutly saying he had not studied the accuracy.

4. X-ray of the bones and a more scientific examination of them: The team that examined the skeletal remains at the Nair hospital was composed by Dr Mohite. He included Dr Sonavane, who was from the anatomy department.

No member was chosen from the radiology department.

That led Pasbola to question why the bones were never X-rayed, except the skull, or subjected to more complex radiological tests like micro-radiography or electron microscopic examination. Ultra violet ray examination. Or even radioactive carbon dating.

The query irked Dr Mohite: "I do not know what investigative process he is speaking about?!"

Pasbola: "To understand the morphological changes and time since death, X-ray and micro-radiography is more precise than the naked eye examination." "Naked eye" was a phrase he emphasised then and several times after that.

Dr Mohite: "No sir."

Pasbola: "Are you aware of the advances made in science in the field of estimation of time since death?"

Dr Mohite shortly: "Yes."

Pasbola: "The traditional morphological methods of examination are considered imprecise and you agree there are better methods."

The forensic expert tolerantly, and not very exasperatedly, explained he was well aware of the latest methods and recited a few more to the room. But he said they were not done in India implying therefore that could not be helped and traditional morphological methods were precise enough.

5. The registers at the forensic department of Nair hospital: There was a lengthy analysis of the various registers used to record entry or departure of documents and articles (bones/medical samples) into Dr Mohite's department.

The registers were brought before the court on Thursday by the doctor and Pasbola quizzed him extensively about the entries for the skeletal remains relating to the Sheena Bora case.

The upshot: The outward registry detailed, in this case, items sent by Dr Mohite and his team on 31/8/2015 to the Nair Dental College (probably the skull for X-raying) but not anything to the Forensic Science Lab in Kalina, north west Mumbai, although items had been sent as per other additional records.

The register was not paginated and Pasbola pointed out to the court, with a triumphant smile, that, during that period, there was a discrepancy in serial numbers of the entries.

From serial number 399 the entries suddenly jumped to No 420, indicating perhaps pages were missing or torn out.

6. Towards the end of his cross-examination of Dr Mohite, Pasbola took permission to show the doctor the video of the exhumation and the related photographs. This turned out to be a rather curious and effective exercise, worthy of some popcorn to accompany it.

Indrani's lawyer Gunjan Mangla played the video back to Dr Mohite. The primary aim of the task was to identify when the skull was located on the day of the exhumation, near Pen, in Raigad district in August 2015.

Mangla and the doctor watched the video dutifully and uneventfully -- while it showed a frenzy of digging activity, it, at no point, showed the discovery of the skull, which should have been a momentous occasion for the videographer.

Pasbola also placed a selection of photographs of the exhumation before the forensic expert. He asked him in which photographs could he discern either the actual identity of the bones or the skull.

Dr Mohite examined each photograph carefully, in his characteristic meticulous manner. About most of the photographs he said: "I cannot say with certainty... I cannot tell... I cannot say which bone... I cannot make out..."

At only two points did he offer: "Pictures 42 and 43 are blurred, so I cannot say with certainty, but picture 42 appears (to be) of (something) rounded therefore likelihood of it being the skull... Picture 23 is blurred, but collectively looking at 22 and 23 it appears to be of the sacrum (bottom of the spine)."

Pasbola wondered why the bones showed roots and clumps of mud sticking to them in many of the photographs, but not later.

Because, though Dr Mohite said the bones had neither been brushed nor washed at the exhumation site, strangely the picture of the "skeletal remains organised in the anatomical position of a skeleton", which was also taken at the site too no longer showed either the mud or the roots.

7. While ending the cross Pasbola narrowly asked Dr Mohite what he knew about Sheena Bora before he set out for the exhumation in August 2015 -- what had he heard from the police and from reports in the newspaper and on the television.

Pasbola: "You knew one thing that the sex of the person was female... You also knew the case pertained to a lady named Sheena Bora... Her photographs and age was known to you." He added that the doctor was aware of when she had disappeared as well.

Dr Mohite admitted to knowing it was about a Sheena Bora since the name was on the police requisition slip, but he denied knowing any further details or seeing her pictures.

Closing the cross examination, Pasbola put forward his accusation: "Doctor, my case is that your estimations with regards to sex, age and time since death are completely erroneous. I put it to you doctor that you were influenced by the prosecution case, the press reports and the police with regards to the age and sex. You had read reports in the (newspapers) and seen it on TV."

The end of each hearing is about all the 'housekeeping' matters related to the case, like the applications put in by the accused and sundry related matters.

Indrani spoke to the judge about yet another bail application that she planned to argue with the help of Pasbola, a new lawyer she had engaged from Delhi and herself.

She was also asked why she had not applied for permission to access her passport and OCI for both banks at which she had accounts. A little puzzled, she coyly sought advice from the judge.

Judge Jagdale, in turn, told her, a smile playing mischievously on his face, in more or less the following words: "You said you needed access to your money pay your lawyers's fees, so now consult them on what you need to do!"

Accused No 4, Peter Mukerjea took the stand twice. Once was about his visit to the dentist that had created objections from the jail superintendent, who was upset that the visit had taken so long and required a jail vehicle for so long.

Peter said he had deliberately not taken the ambulance which had been provided for him because he was aware of the pressure on it (there is apparently just one for Arthur Road jail for emergencies) and had opted for the van and that the length of time was due to traffic and for the one hour procedure it takes him to get back inside the jail.

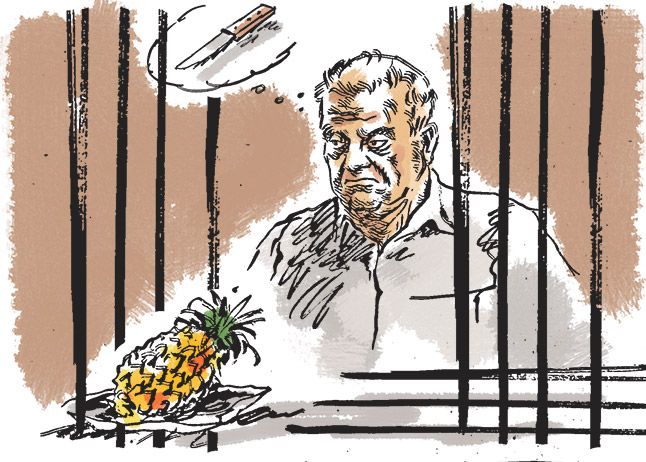

The second issue related to his dietary requirements. Post his triple or quadruple bypass he was only allowed boiled, unsalted vegetables and fruits. He was getting fruits, but no implement to cut them with.

He told the judge, sadly: "I have tried and it is very difficult, your honour." His statement quickly brought up the imagery of Peter trying to cut a pineapple with his teeth or a papaya with a pen or a toothbrush.

He therefore needed access to pre-cut fruit.

Some cut fruit arrived in a plastic packet for the lunch recess for Peter before the accused returned to jail.

The Sheena Bora trial will resume on Thursday, October 24.

© 2025

© 2025