'US counter-terrorism policy was encouraging and emboldening the Indians to deal with the problem of Pakistani-supported terrorism once and for all.'

'The US had been trying to browbeat Pakistan into doing what it wants, with very limited success.'

In New York, Robert L Grenier, the CIA chief in Islamabad during 9/11, spoke about American policy in Afghanistan and Pakistan. P Rajendran/Rediff.com listens in.

“I used to say it would be a splendid little war if it weren’t for Washington,” Robert L Grenier, former Central Intelligence Agency chief of station in Islamabad, said, speaking of America’s involvement in Afghanistan -- which he described as the First American War in Afghanistan.

Grenier was speaking at an event organised by New America NYC, a wing of the Washington, DC-based think tank, the New America Foundation. The talk hosted by former Pakistan ambassador Hussain Haqqani was to promote Grenier’s book, 88 Days to Kandahar.

“I wrote the book essentially as an adventure story... bracketed by the story of how it was we won, as I thought, the First American Afghan War, how we lost the second, and how we may yet be drawn into a third,” said Grenier.

More than an adventure, Grenier’s account is, perhaps self-servingly, that of a foot soldier frustrated by a bunch of politicking policymakers who ought to have understood the realities on the ground before issuing orders, most of them delivered on the basis of internal or public expectation.

Grenier described the unreal moment when then CIA director George Tenet woke him in Islamabad a few days after 9/11 and asked him what to do.

‘Should we bomb empty camps?’ Tenet asked his man in Islamabad, who was still befuddled with sleep and the novel experience on being asked for advice.

When he heard Tenet asking him what to do, Grenier recalled he told himself, ‘If we didn’t know we were in trouble before, I knew we were in trouble now.’

Recovering, he tried to convince Tenet, it was a political problem, not a military one.

‘We need a responsible governing authority in Afghanistan that can control this territory, that will deny this as a safe haven for terrorists,’ Grenier recalls telling Tenet. ‘That’s it. That’s all we need. If the Taliban can be that force, well then fine. Or if (not) the Taliban leadership, then some other faction within the Taliban can be that force, that, too, should be fine. We should be able to accept that, unlovely though (the options) are.’

If the US made common cause with the Northern Alliance to fight the Taliban, Grenier said it would unite the tribals under the clerics. Instead, he said, the local Pashtuns had to be recruited into the effort to get rid of Al Qaeda.

‘If this looks like an American invasion, it looks like we are trying to conquer their country, to establish permanent bases, this will go very bad for us,’ Grenier recalled telling Tenet.

‘We saw how it went with the Soviets (in 1979). We saw how it went with the British (in the 19th century). We could reprise that history if we were not very, very careful.’

Going by what he says now, Grenier certainly tried.

He described frenzied efforts to lobby the Pashtuns, who, battle-hardened by the fight against the Soviets as they were, were terrified of the Taliban.

“Most of the tribal leaders wanted to see how things would go before sticking their heads,” he said. Finally, only two leaders, Hamid Karzai and Gul Agha Sherzai, were left to take up the fight to a successful conclusion 88 days later.

He described the highs -- the rescue of some aid workers and the military victories -- and the lows -- such as the death of rebel leaders Ahmad Massoud and Abdul Haq, and the escape of Osama bin Laden, the man responsible for 9/11, from Tora Bora, where the Arab elements of Al Qaeda made their last stand before fleeing through the porous Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

He described the highs -- the rescue of some aid workers and the military victories -- and the lows -- such as the death of rebel leaders Ahmad Massoud and Abdul Haq, and the escape of Osama bin Laden, the man responsible for 9/11, from Tora Bora, where the Arab elements of Al Qaeda made their last stand before fleeing through the porous Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

Grenier described the CIA’s fears that a group of Pakistani scientists may have given a nuclear bomb -- “or at least nuclear material” -- to Al Qaeda. It got people’s attention in Washington, he said.

Grenier, who has described his indebtedness to the Pakistani army and the Inter-Services Intelligence in his book, described the ‘war hysteria’ that resulted in Pakistani and Indian troops facing off across their common border in May 2002.

The face-off came five months after terrorists attacked the Indian Parliament, and soon after Pakistani terrorists entered an Indian Army camp in Kashmir, killing 31 people and wounding 47, many of them wives and children of the soldiers.

As he described in his book, Grenier felt ‘US counterterrorism policy was encouraging and emboldening the Indians to deal with the problem of Pakistani-supported terrorism once and for all.’

He also describes how earlier, in April the same year, when an aide of then defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld asked him, ‘Say, isn’t this stuff that is going on in Kashmir terrorism?’

Describing himself as aghast by this pronouncement of someone uninstructed on South Asian history, Grenier said he responded to this by saying, ‘There’s a long history behind this, which dates back to 1947 and beyond. It would be a big mistake to deal with terrorism in Kashmir in isolation from the underlying dispute. We can’t think about addressing terrorism unless we’re willing to seriously address this dispute.’

In a later conversation with Haqqani, he conceded that bin Laden only wanted the US military to leave the Islamic world, but did not argue for using history as a reason to ignore terrorism.

“The victory that we thought we’d won actually came far too easily,” Grenier said, speaking about the defeat of the Taliban. “I never thought it would be that easy. It was seductive, so much so that we did not know why and how we had actually won this war, as we thought. Our attention shifted. America went off to Iraq.”

Grenier went off himself to lead the CIA effort in Iraq for two-and-a-half years. By the time he returned, as director of the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Centre in 2005, to focus once again on Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“Already, the situation was beginning to slip from our grasp,” he said. “We didn’t fully realize it yet, but the Taliban was beginning to reassert itself. And the reaction of America at that point was very unfortunate. By that time we’d forgotten all of the lessons, (lost) all of the keys to our success in what I’d like to call the first American Afghan War.”

“We did everything that we said we shouldn’t do at the outset. It was no longer an Afghan-led effort. It was an American-led effort. We had up to 100,000 US troops, 40,000 additional troops from NATO countries. We were spending a $100 billion a year. We completely overwhelmed the small, primitive, agrarian country, achieving what no Afghan government can conceivably sustain...”

The upshot, he said, is that Afghanistan is again lapsing into civil war.

“And having created tremendous problems by having tried to do too much between 2005 and the present, now I think we are making a mistake,” Grenier said.

“We are compounding our error by doing too little. I’m very concerned about the future of the government in Kabul, and I very much fear that at some point in the not too distant future we may be called again to fight the Third American Afghan war.”

After discussing his book, Grenier went on to a question-and-answer session with Haqqani, who at one time was arrested and tortured, and finally exiled from his home country.

“How (much does) Washington intrigue and politics actually shape, more than what’s happening on the ground, the decision about when America goes to war, to what extent, and for how long?” Haqqani, a friend of Grenier, asked.

Grenier said that he wished he could disagree with him, but that he often felt like the one-eyed man in the land of the blind.

Grenier said that he wished he could disagree with him, but that he often felt like the one-eyed man in the land of the blind.

“It was almost as though the whole point of being a superpower was that it really didn’t matter what foreigners thought,” he said.

“As the ambassador said, they tended to see the world in a very binary way. There were people who were doing things the way that we wanted, and other people who either had to be suborned or coerced into doing what it was that we wanted, when in fact people in a world where technology is tending to level the differences among us reliably will not do things that they don’t think is in their own interest.”

The US, he said, had been trying to browbeat Pakistan into doing what it wants with very limited success.

“During the course of the Afghan campaign dealing with Washington was a great trial and a great challenge because there was this tendency to think that everything has to flow from (there),” Grenier added. “‘We’re going to make the decisions at the end of the day,’ and it made life very uncomfortable.”

“I used to say it would be a splendid little war if it weren’t for Washington.”

He went on to describe his early efforts -- on September 25, 2001 -- to build a coalition around senior Taliban leader Mullah Osmani.

‘We don’t like this bin Laden either. We didn’t know he was going to do what he did. We certainly didn’t sanction it. We have a (common) problem. We need to work together to solve it,’ Osmani told him. Grenier pointed out that the ulema -- the group of Islamic scholars -- had censured bin Laden.

But by October 2, 2001, the momentum for war was building up inexorably in Washington, Grenier said. And, against the tide, he tried again to convince the Taliban leader to come over.

“I was convinced I was wrecking my career... I met with Osmani... (at an ISI safehouse).”

“He knew that the Americans were coming, and he knew that his leader would not make a deal. By the end, he was in a corner. He’s a huge man and I could see him shrink in front of my eyes. He took his turban off his head. I’ve never seen a Pashtun do that (except in family circumstances).”

“He took off his turban and asked, ‘What should I do?’ That was exactly the moment I was hoping for.”

Grenier asked Mullah Osmani to seize control, including the radio station, push top Taliban leader Mullah Omar aside.

“‘You have to say that for the good of the country, for the good of the movement... I’m following the guidance of the ulema and we are going to ban the Arabs, we are going to ban bin Laden.’ And then quietly... he would hand bin Laden over to us,” Grenier said.

“(Osmani) said, ‘I’ll do it’,” the former spy said. “He stood up and hugged me. It was extraordinary. It was as if a great weight had been lifted off his shoulders.”

Grenier said they gorged themselves on rice and mutton. But then, once back among the Taliban, Osmani vacillated again. Once the bombing began, he would do nothing. Osmani died in a bombing raid in December 2006.

Haqqani quipped that he and Grenier agreed to keep their differences to the minimum, and so would talk about Pakistani intelligence last.

“The guy who is the CIA station chief and who has mutton and rice with them and the guy who ends up in their prison. Um, different perspectives,” Haqqani said to some laughter, referring perhaps to his arrest and incarceration in 1999.

Haqqani went on to ask Grenier about people Jalaluddin Haqqani (“who stole my family name. He’s actually Jalaluddin of the Zadran tribe”), a former CIA friend who demanded $80,000 just to meet Grenier. “How many of these former Taliban were living in a different era and did not know how American priorities had changed (after funding the Afghans’ war against the Soviets in 1979),” he asked.

Many of them, Grenier responded, actually had a lot of experience with the Americans, knowing them to be good for money.

Many of them, Grenier responded, actually had a lot of experience with the Americans, knowing them to be good for money.

“It’s often said you can’t buy an Afghan, but you can rent him,” he joked. “If we could have rented them long enough... back before 9/11, I would have been very happy to strike that deal.”

Grenier spoke of the tension between tribal leaders and clerics, which resulted in the former resenting the rise of the Taliban and so being motivated to work with the US if only they had not been crippled by fear.

“They knew what happened when you crossed the Taliban and you lost,” Grenier said, citing first the example of Najibullah, the last pro-Soviet Afghan president, who was tortured, castrated, dragged behind a truck and finally -- perhaps mercifully -- hanged, and then another Pashtun leader, Abdul Haq, who went back into Afghanistan and was killed by the Taliban for his pains.

He spoke of an officer who unsuccessfully asked a Pashtun warlord who had been a hero against the Soviets to go rally his troops.

“This CIA case officer -- actually a very mild-mannered fellow -- finally became enraged. He told the man in Dari, ‘You’re not a man, you’re a woman. You’re a disgrace to your tribe’,” Grenier said, adding that the Dari terms used sounded much worse than it did in English. “This would have been cause of a blood feud. And he sat there and took it.”

He said it took some time to find leaders like Gul Agha and Hamid Karzai to take up the fight against the Taliban.

To another question about perceptions about the impiety of the US having stoked a strong response in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Grenier said even in the US, people responded to that with comments about those in the Muslim world not liking American freedom, culture, or wanting to Islamise the whole world.

“I don’t think they wanted to turn Ohio into an emirate,” he said, to some tittering. “What they really wanted to do is recreate the old Islamic emirate. They wanted to save the Islamic world for Islam as they understood it. They saw a United States whose power, I think, they greatly exaggerated, as standing in their way,” he said, asserting that these people felt regimes like those in Saudi Arabia, Jordan or others would fall like dominoes without American support.

Asserting that bin Laden had been clear that all he wanted was for the US to leave the Islamic world. “Basically he was saying, ‘We will attack you, we will go on attacking you, we will go on killing Americans until you leave. It’s as simple as that.’”

Haqqani asked what Grenier would tell a Muslim like himself (Haqqani) who also sees bin Laden and his kind as the enemy because each group’s version of Islam is unacceptable to the other, resulting in more Muslims being killed than Americans.

Haqqani argued if the US had also distinguished between the two kinds of followers of Islam, it might ensure a better reception for its policies in South Asia.

Grenier said it would be a big mistake to let the violent elements define themselves as the defenders of Islam.

“At the end of the day, the struggle for the heart and the future of the Islamic world is where people like the ambassador (nodding toward Haqqani) are fighting a death struggle with others of a fundamentalist cast.”

While America has a stake in the struggle, he said, “We are outside that struggle.”

Grenier felt that people in Washington did not often understand that it was not a PR problem, but a policy problem.

“It’s not just that they (those in the Muslim world) are misperceiving us,” he said; “it’s what we’re doing.”

Images: Top: A scene from Afghanistan. Photograph: Ahmad Masood/Reuters.

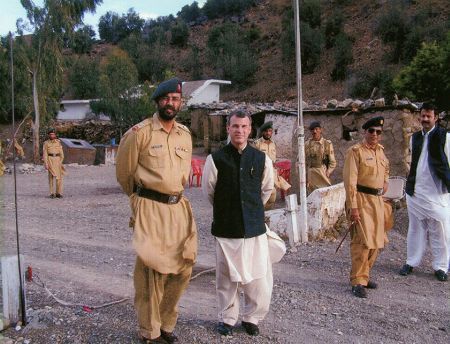

Middle: Robert L Grenier with Pakistan soldiers on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

Bottom: Afghan policemen with a captured Taliban fighter in Zabol province, March 22, 2008. Photograph: Goran Tomasevic/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025