'I had once gone to Kashmir with him and his wife. He would talk to the boatmen, the watchmen, at the dargahs he would ask so many questions. He always had a notebook and would write down everything...'

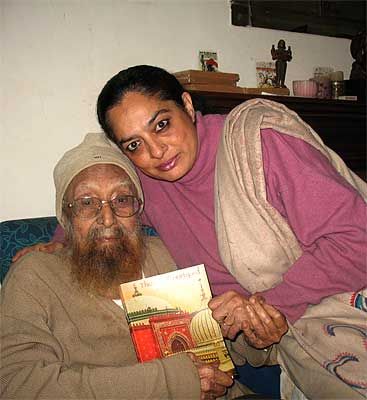

Sadia Dehlvi on her 30-year-old friendship with Khushwant Singh.

He would have been very happy to see the people who had come to his home after he passed away. The prime minister, Sonia Gandhi, L K Advani, Omar Abdullah and a host of others... He would have loved that scene.

He would have flowered in that scenario. He liked attention. He loved controversy. He used to advise me, 'When you write -- inform, provoke, abuse.'

In the last few years he did not meet many people though he was a people's person. He thrived on controversies. He enjoyed abuse more than the adulation of his fans.

He was out to prove that he was a dirty old man, a drunk and a lecherous womaniser. He was none of the above.

He was a gentleman and a softie who was often bullied by his friends.

Seven years back when I was about to release my book Sufism, The Heart of Islam, I wanted him to be there. He said he was not up to it and would not be able to make it. I told him he must try, but he said no, so I said okay.

The next time when I came to visit him he asked, 'Bol, kab aana hai.' I was so happy that I immediately gave him a hug. He dedicated his book, Not a Nice Man to Know to me and wrote, 'To Sadia Dehlvi who has added to my notoriety and affection.'

I had dedicated my first book to my mother and wanted to dedicate the second book to him and Delhi, the city we both loved so much. He was upset. He said that when he dedicated a book to me, it was only to me and he wasn't going to share the honours with anyone or any city even though he loved Delhi.

I relented and dedicated the book, The Sufi Courtyard - Dargahs of Delhi only to him.

I never worked for him, but we did work together. I produced a television serial called Not a Nice Man to Know. He was the anchor of the show, but I had to bully him into agreeing to do it.

He interviewed Protima Bedi, Sharmila Tagore among others. We interviewed women from different fields.

It was very difficult to make him change his clothes for the show. They were always shabby and dirty. He refused when I told him that he had to wear clean clothes on TV.

I pleaded with his wife, took a pair of his clothes to the tailor and got a new pair stitched that I kept in the studio.

When I asked him to wear it he said, "I have the reputation of the worst dressed man in the country and I want to keep it." I forced him, saying that the channel would not pay me if he dressed shabbily. He said, "Achha baba," but was very unhappy with the new and clean clothes.

When he was paid for hosting the show, he said, "I have so much money, I don't know what to do with it, you keep it." He didn't want it. I had to force him to accept it.

He was not very money minded. I doubt he knew how much money he actually had.

Among his books he was very proud of the book A History of the Sikhs, Train to Pakistan and his translations of Urdu poetry. He liked his affiliation to Muslims and Muslim works. He used to get up listening to the Quran everyday on his radio.

He had the Kalma' -- the Muslim declaration of faith -- in his house and he used to show it to Muslim visitors. On his curtains were written the Muslim greetings, Salam walaikum, walaikum as salam.

When he was the editor of the Hindustan Times, above his head, used to hang a wooden Allah. These words are now in his home.

He felt a lot for the Muslims. He felt that injustice was being done to them by a few who hated them because they were Muslims. He hated communalism.

He did not like the idea of Narendra Modi becoming prime minister. He had criticised L K Advani for the demolition of the Babri Masjid. He had told him what he thought without mincing words.

If any writers came to meet him and they had even a slant of religions intolerance or any slant to the right -- he would refuse to meet them.

He was fond of Pakistan and a supporter for Indo-Pak peace. Over a decade ago he went back to his village in Pakistan. He said, "This is my Haj." He was very emotional about it. Talking about it brought tears to his eyes.

The first time that I met him was at an exhibition. He just walked up to me and said, "Why are you so beautiful?" I recognised him, he was our country's first celebrity journalist.

I replied, "Because I am a beautiful person." He invited me home the next minute, 'Tomorrow 7 pm, my home.'

I went the next day and since then we have been friends.

I have known him for 30 odd years. I last met him two weeks ago, gave him a hug and sat with him for 10, 15 minutes. I used to go there once a fortnight to spend some time with him.

I remember he was so proud to tell me, "I have never missed a deadline in my entire life, whenever I had to deliver I always did and on time." He was very proud of the Padma Vibhushan and said that he had never asked for it. He had returned the Padma Shri (after Operation Blue Star).

He was also very particular about asking for favours. "I have never asked for a personal favour," he always said.

For the past few years he had become very reflective about life. He was very disturbed by the growing religious intolerance in our country.

He was humble, generous and mentored so many journalists. All kinds of people used to come and meet him and ask him for his help. He helped with jobs, promotions, children's admissions. He knew a huge variety of people.

He didn't like boring people and name droppers. Lately he has been quite childish when talking about his stature. "The prime minister sent me flowers," he would proudly claim.

He went away, alert till the last minute.

He used to talk about his brother who passed away a few months ago. He said he was the only one left among his siblings. "My brother passed away peacefully in his sleep and I have the same idea."

Lately he rested alone most times. He preferred spending his time with poetry. He would have a single malt and read Ghalib. He used to say, "Ghalib is my companion."

I have a lot of recordings of him reciting poetry, talking, laughing, I have his voice on my phone.

He was a very good human being. He will be remembered for his work by people who did not know him personally. The people who knew him will remember him for the person he was.

He was larger than his work. His honesty, humility, value system, friendship was very important to him. He was the best friend one could have. He has touched so many lives.

There are very few people like him in this world. I don't think we will see another Khushwant Singh. He was fun, an intellectual, serious, he loved people, he loved life, he had the spirit of enquiry.

I had once gone to Kashmir with him and his wife. He would talk to the boatmen, the watchmen, at the dargahs we visited he would ask so many questions. He always had a notebook and he would write down everything. I learnt that from him. A name of a flower or a design, he would jot down everything.

When anyone came to meet him, he would ask them so many questions about their life. He wanted to know everything about them.

He used to be fascinated by death. He always said, "I am not an atheist, I am agnostic, I don't deny God. I am saying I don't know."

I have been very fortunate to know him closely. He has mentored and shaped my life. I will always remember him. The people whose lives he touched will always remember him.

Sadia Dehlvi is a columnist and author. She spoke to Rediff.com's A Ganesh Nadar.

Image: Khushwant Singh with Sadia Dehlvi and her book, The Sufi Courtyard - Dargahs of Delhi, which is dedicated to him. Photograph, courtesy, Sadia Dehlvi.

© 2025

© 2025