'There is no one who can fill the vacuum created by the passing of Girija Devi,' mourns Sunita Budhiraja.

It was the year 2008.

I learnt that Girija Devi was going to be singing at the Viceregal Lodge at Delhi University.

I had just moved to Delhi, did not possess a car and had lost the habit of travelling by autorickshaw.

But it had been a while since I had heard Girija Devi live and, willy-nilly, found a way to attend the concert.

The hall that can accommodate over a thousand persons was packed with young music lovers, most of them seated on the floor.

I made my way through the throng and sat on the durrie, in anticipation of what would prove to be one of the most magical musical evenings of my life.

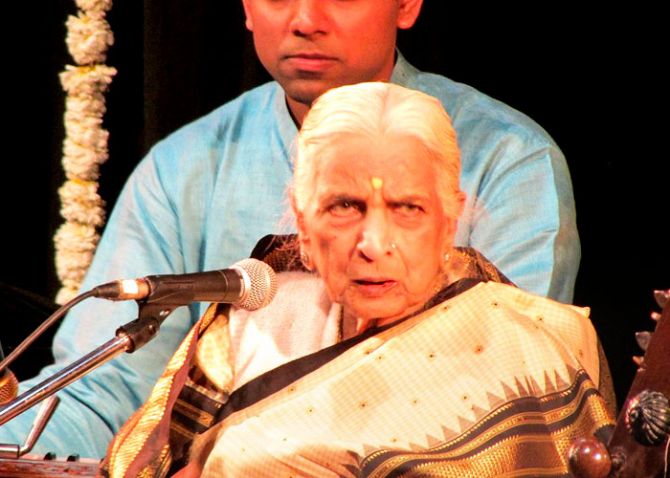

Girija Devi entered to a standing ovation, dressed in an off-white sari. She took her aasana (seated posture) on the stage.

The moment she began her aalap, my heart nearly stopped. And I knew that the purity of her voice touched the soul of everyone present.

She sang a thumri in Raga Bihag and then indicated the end of her recital. But, of course, the audience wanted more.

I suggested that she sing Jhoola.

"Which one?" she asked in Hindi.

"Siya sang jhoolen bagiya mein Ram Lalna," I answered.

"Yeh hai achchhe sunnewale ki pehchan. Hum yahi gayenge (This is the mark of a connoisseur. This is the one I will sing)." And she obliged.

Girija Devi always developed a beautiful rapport with her audience.

She talked of her age, introduced co-artistes, gave her disciples the opportunity to sing with her and appreciated them publicly.

At that concert, while the audience begged for more, she was firm that she needed to vacate the stage for her "chhote bhai (younger brother) Hari", flute maestro Hariprasad Chaurasia.

Girija Devi was a childhood love for me. A case of love at first sight.

I was seven or eight years old. My mother often took my younger brother and me to all-night music festivals.

We were made to sit through the night listening to legendary artistes, often dozing off and then waking to the sound of applause.

My mother would say, "Kaan mein sur padna chahiye (the music should reach the ears)."

I vividly recall seeing Girija Devi at one of those concerts. I was dazzled by her elegant beige sari, salt and pepper hair, and the diamond nose pin that glinted when the stage lights fell on it.

The image of that sparkling diamond nose pin stayed with me for years and, much later, I decided to defy my mother and have my nose pierced just so I could wear a diamond like Girija Devi.

Memories of Girija Devi will always stay with me.

Once, when it was still the age of Doordarshan and black-and-white television, I compered some music programmes.

Naina Devi was producing a programme on the Poorab Ang Gayaki with the legendary Rasoolan Bai and Siddheshwari Devi. I entered the studio to find the two greats chatting with each other.

"Who will take the Benares Gharana gayaki (singing style) forward after we are gone?" asked Rasoolan Bai.

"Apni Girija hai na (Why, we have our Girija)," said Siddheshwari Devi.

What faith and confidence these doyennes of Benares had in the young Girija Devi.

I did not realise the importance of their discussion at the time. Today, I know what they meant -- because there is no one who can fill the vacuum created by the passing of Girija Devi.

Yet another memory...

In 2003, Ronu Majumdar organised a morning concert in Mumbai titled Banaras Utsav.

The concert began with a performance by Ronu, and was to also feature Girija Devi, Kishan Maharaj and Bismillah Khan.

Ronu invited me to compere the programme. What bigger honour could I have sought?

But to introduce luminaries who needed no introduction was a challenging task. And what could I say about Girija Devi?

I decided to tell a story, of a woodcutter whose axe had fallen into a river.

Seeing him weep, the god of water emerged and offered him an axe of gold, which the woodcutter declined.

Then he was offered a silver axe, which too the woodcutter refused.

Finally, the god gave him his own axe as well as the gold and silver ones.

"Friends," I said, "the woodcutter was a singer too."

Later, on the banks of the Ganges in Benares, he lost his music. The water god attempted to fish it out.

"First, he came up with Girija Devi, next Girija Devi and the third time, too, Girija Devi. Music is Benares and Benares is indeed Girija Devi."

Girija Devi remembered me from then on.

Girija Devi started lessons as a child of five, first with Sarju Prasad Mishra and later Shrichand Mishra.

She took the Banarasi Ang Gayaki to new heights.

When she sang thumris, her rendition was "sahaj (simple)". She would say, "Woh thumri hi kya jisme shabd thumak kar na niklen? (What kind of a thumri is it if the words do not dance?)"

She excelled in all six styles of thumri. She sang Chaiti, Kajri and Dadra with ease. Swarass (musical notes) were hers to command.

Most people addressed her as Appaji.

She was the unquestioned queen of thumri, but she was also a simple, warm-hearted lady. She believed in building relationships.

She tied rakhis to Amjad Ali Khan and Maniram, elder brother and guru of Pandit Jasraj. And she sang Chhati ke geet when Maniram's daughter Yogai gave birth to a baby girl.

Girija Devi came to Hyderabad for the Motiram Maniram Festival.

Jasraj, along with his family and some disciples, was staying in my house.

Girija Devi would have meals with us and sleep at my friend and neighbour Manik Arke's house. She was happy with simple roti, dal, chawal. She wanted to be treated like a family member.

But when she went on stage, she was as the goddess in a temple.

When she sang Jhoola dheere se jhulao Banwari, arre Sanwariya, one could almost see Radha on the swing.

When she sang Chadhat chalet chit lagena Rama baba ke bhawanwa with Bismillah Khan, one could feel the longing a bride visiting her father's home felt for her absent husband.

Girija Devi played with words, with bandishes, so much that they came alive in her swaras.

Kolkata was her second home. But Benares remained her first love, a place of which Bismillah Khan said, 'Ras yahan banabanaya hai (musical culture is inherent here)'.

I can't now say how much rasa remains in Benares (now Varanasi) when in place of the swaras and bols of Bismillah Khan's shehnai, Kishan Maharaj's tabla and Girija Devi's bandishes, there is now only silence.

© 2025

© 2025