'The colloquial language forced a turn to the recent past and I thought about the hangings of men like Afzal Guru and Yakub Memon.'

'Whatever their deeds, proven or still in doubt, did their deaths not deserve to be mourned by a sister, wife, or child?'

A fascinating excerpt from Amitava Kumar's Writing Badly Is Easy.

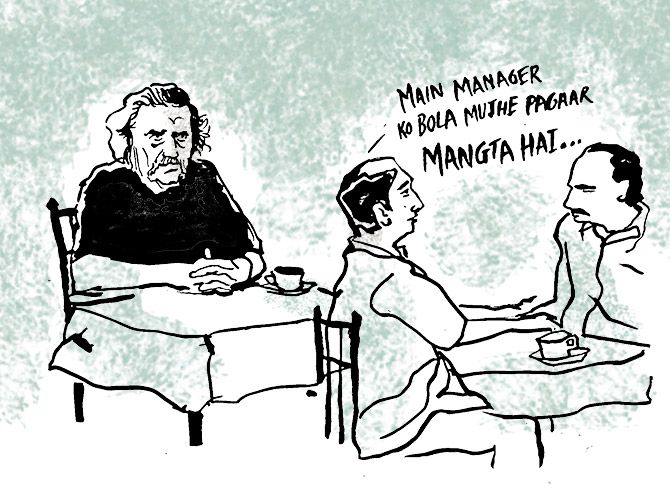

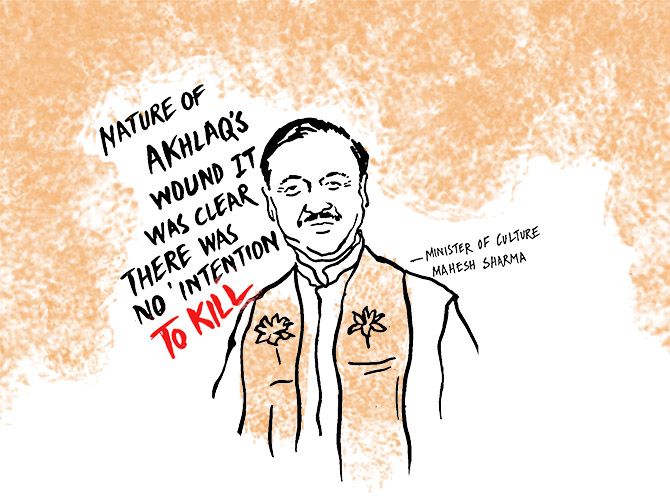

All Illustrations: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

The poet Arun Kolatkar, author of a stunning book, Jejuri, also wrote poems in the language of Mumbai's streets, the rough mix of Marathi and Hindi that would later find a flowering in Bollywood films.

Kolatkar was sitting in an Irani restaurant when he heard one man narrate to another the following story: 'Main manager ko bola mujhe pagaar mangta hai/manager bola company ke rule se pagaar ek tarikh ko milega/uski ghadi table pay padi thi/maine ghadi uthake liya/aur manager ko police chowki ka rasta dikhaya/bola agar complaint karna hai to karlo/mere rule se pagaar ajhee hoga.'

Kolatkar turned Bombay patois into American English and his translation went like this: 'i want my pay i said/to the manager/you'll get paid said/the manager/but not before the first/don't you know the rules?/coolly I picked up his wrist watch/that lay on his table/ wanna bring in the cops/i said/'cordin to my rules/listen baby/i get paid when i say so.'

I learned about Kolatkar's experiment from the poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra.

He too, in his fine translation of Kabir, infused the medieval bhakti poet's verses with American slang. '"Me shogun."/"Me bigwig."/"Me the chief's son./I make the rules here."/It's a load of crap./Laughing, skipping,/Tumbling, they're all/Headed for Deathville./In the blink/of an eye, says Kabir,/The king will be/Separated from his kingdom.'

To save Kabir from smothering under solemn religiosity, and to ensure that his verses retain their earthiness, we must keep him colloquial.

This is true of other old texts too.

I watched a performance of Antigone in Brooklyn with Juliette Binoche in the title role.

I had only seen Binoche in films before that.

Her wide-apart eyes, hair often cut short, I had seen her surrounded by succulent fruit, or desserts and chocolate, or beautiful landscapes.

In Antigone she knelt in the bleak desert, mourning her dead brother lying unburied because he was a traitor

The play's two millennia old, but on stage everything was modern.

Antigone wore an elegant black outfit and heels.

The most recognisably contemporary aspect of the play was the language itself.

In poet Anne Carson's translation of the play, the words appeared plucked from present-day parlance.

The colloquial language forced a turn to the recent past and I thought about the hangings of men like Afzal Guru and Yakub Memon.

Whatever their deeds, proven or still in doubt, did their deaths not deserve to be mourned by a sister, wife, or child?

When I was in college in Delhi in the early eighties, I watched Girish Karnad's Tughlaq with Manohar Singh in the lead.

The play was about the possibility of political idealism turning into tyranny.

Karnad was using the 14th century sultan as a device to comment on the disillusionment of his generation.

Tughlaq's combination of vision and tyranny had a parallel in the problematic aspects of Jawaharlal Nehru's leadership, and the play later found new resonance when Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency.

In 2018 I wrote to Karnad and asked him about the murder of Mohammad Akhlaq in Dadri over the suspicion of beef-eating.

Was there an old story that would explain the present-day horror of lynchings?

In response, Karnad said that long ago he had written a play called Bali: The Sacrifice based on an ancient Jain myth.

The myth mocked Brahmins who, yielding to the influence of Jainism and Buddhism, had started substituting animals made of dough for live sacrificial animals, arguing that they were thereby being non-violent.

The myth declared that violence in intention -- mental indulgence in violence -- is as dehumanising and corrupting as real violence.

In Bali, King Yashodhara is asked to perform an animal sacrifice.

But he is a Jain and his faith forbids violence.

As a compromise, instead of a live animal he decides to sacrifice a rooster made of dough.

And then, just as he is about to plunge the knife into it, the rooster begins to crow.

The Hindi translation of Bali was launched in 2018 at the Jagaran Literature Festival in Lucknow.

Karnad told me that instead of reading passages from the play he had merely quoted the BJP's Minister of Culture, Mahesh Sharma, who had declared that from the nature of Akhlaq's wound it was clear there was no 'intention to kill' and that 'accident' was a more accurate description than 'murder'.

Karnad also pointed to what the prime minister's long silence in the aftermath of the event implied in the context of the myth.

Karnad said, 'The speeches and the silence could have been part of my play.'

Excerpted from Writing Badly Is Easy by Amitava Kumar, with the kind permission of the publishers, Aleph Book Company.

© 2025

© 2025